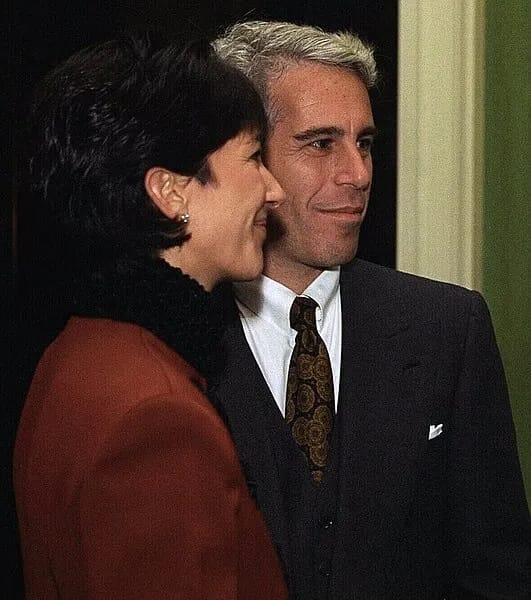

Ghislaine Maxwell sits in a federal prison, however comfortable her Club Fed prison may be, convicted of sex trafficking and conspiracy for her role in Jeffrey Epstein’s abuse of minors. She is appealing to the Supreme Court, arguing that she should never have been prosecuted at all. Her claim rests on a 2007–2008 non‑prosecution agreement (NPA) that Epstein struck with the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the Southern District of Florida. That deal, negotiated by then‑U.S. Attorney Alexander Acosta, allowed Epstein to plead guilty to two state charges, serve a light sentence, and — most controversially — included a clause that said the “United States” would not prosecute his “potential co‑conspirators.”

Maxwell’s lawyers argue that this language should have shielded her. The Department of Justice counters that the deal was limited to Florida, that Maxwell was not a party to it, and that her crimes in New York fell outside its scope. The courts have agreed with the government.

But this raises a deeper, more troubling question: if the plea deal was meaningless for Maxwell, why has it been treated as meaningful for everyone else? Why have none of Epstein’s other alleged accomplices — some of whom were explicitly referenced in the Florida agreement — been prosecuted?

The 2007–2008 plea deal was extraordinary. Epstein faced a 53‑page federal indictment that could have put him away for life. Instead, he pleaded guilty to two state charges of soliciting prostitution from a minor, served 13 months in a county jail with liberal work‑release privileges, and registered as a sex offender.

The most shocking element was the immunity clause. It stated that “the United States” would not prosecute Epstein’s “potential co‑conspirators.” Four individuals were named in the agreement (their names redacted in public filings), but the language was broad enough to suggest protection for others as well.

For years, this clause was treated as a shield. Prosecutors in other districts hesitated to bring charges, citing the deal. Victims were told that Epstein’s associates could not be touched.

When Epstein was arrested again in 2019 in New York, the Florida deal was suddenly reinterpreted. Prosecutors in the Southern District of New York argued that the NPA was limited to Florida, did not bind other districts, and did not cover crimes committed after 2007.

Maxwell was indicted in 2020 and convicted in 2021. The Second Circuit Court of Appeals upheld her conviction, rejecting her argument that the Florida deal immunized her. The Justice Department told the Supreme Court the same: the plea deal was local, not national.

In other words, the government decided the deal was meaningless for Maxwell.

But if the deal was meaningless for Maxwell, why has it been treated as meaningful for everyone else?

- Named Co‑Conspirators: The Florida agreement explicitly referenced four individuals. If the deal doesn’t bind prosecutors outside Florida, why haven’t those individuals been charged in New York or elsewhere?

- Other Associates: Epstein’s social circle included powerful men in politics, business, and royalty. Flight logs, testimony, and victim statements have named dozens of individuals. If Maxwell could be prosecuted despite the deal, why not them?

- Ongoing Crimes: The government has argued that Maxwell’s crimes extended beyond 2007. Surely the same could be said of others. Why hasn’t the Justice Department investigated whether Epstein’s associates continued offending after the Florida deal?

The contradiction is glaring. The plea deal was treated as ironclad when it came to protecting others, but as irrelevant when it came to Maxwell.

The Role of Power and Influence

One explanation is power. Epstein cultivated relationships with some of the most influential men in the world. His homes were filled with cameras, and celebrities and politicians often accompanied his flights. He was a financier, a fixer, and — according to many victims — a blackmailer.

Prosecuting Maxwell was politically safe. She was already notorious, already vilified, and lacked the kind of institutional power that Epstein’s male associates wielded—going after her allowed the government to claim accountability without touching the most powerful figures in Epstein’s orbit.

For survivors, the selective prosecution feels like betrayal. Many have testified that Epstein did not act alone, that other men abused them, that Maxwell was one of several facilitators. Yet only Maxwell has faced justice.

The plea deal has become a convenient excuse. For years, victims were told that nothing could be done because of the NPA. Now they are told that the NPA doesn’t apply to Maxwell — but still, no one else is charged.

This inconsistency undermines trust in the justice system. It suggests that accountability depends not on the law but on who you are and whom you know.

Legally, prosecutors can argue that Maxwell’s case was unique: her crimes were ongoing, her role was central, and her conduct fell squarely within the jurisdiction of New York. But from a public perspective, the distinction feels hollow.

If the government can reinterpret the plea deal to prosecute Maxwell, it can reinterpret it to prosecute others as well. The fact that it hasn’t raises questions about selective enforcement and the protection of powerful men.

The Epstein case is not unique. Throughout American history, plea deals, settlements, and legal technicalities have been used to shield the powerful while punishing the less powerful. From corporate executives to political elites, accountability often stops short of those at the very top.

Maxwell’s prosecution fits this pattern. She is punished, but the men who allegedly abused girls alongside Epstein remain untouched. The message is clear: some people are above the law.

This post originally appeared on Medium and is edited and republished with author's permission. Read more of William Spivey's work on Medium. And if you dig his words, buy the man a coffee.