As a young man, I witnessed the Civil Rights Movement without a complete understanding of what I was seeing. There might have been brief coverage of civil rights protests in states far away. I was eight when Malcolm X was assassinated, and the coverage on the three television channels was minimal. The first mosque in Minnesota wouldn’t open for another 33 years. I don’t recall having seen a Black Muslim until I went to college. In my hometown of Minneapolis, there was no marching in the streets when Malcolm died.

I was eleven when riots erupted in North Minneapolis after the mistreatment of a Black woman by police during the Aquatennial Parade. I attended church every Sunday in North Minneapolis, but I lived in South Minneapolis. I might as well have been a hundred miles away. Minneapolis faced similar issues to those in the Southern United States—unequal treatment of African Americans in business, politics, education, and housing. There were no jobs for Black youth, but I was eleven, what did I know of unemployment? The riots lasted three days, and the governor called out the National Guard.

I was unaware that restrictive housing covenants would have kept me from living in my home at 4220 Oakland Ave until a few years before my stepfather bought his home. A friend my age, Ronald Judy, later chronicled what I didn’t know in an interview. Here is a description of what I lived through, but was unaware of at the time. A restrictive covenant previously covered my home. My grandparents lived in a Tilsenbilt home on 40th Street and 5th Avenue.

“Minneapolis used restrictive housing covenants to keep black families out of certain neighborhoods. What this meant with respect to the Southside, was that there were virtually no blacks south of 42nd Street before 1956. The famous exception being Arthur and Edith Lee who moved into 4600 Columbus Avenue in 1931. The harassment that they suffered was a clear indication, however, of how determined the white people were to maintain segregation, and they left in 1933. A significant wave of blacks started moving south of 42nd Street in the late 1950s however, due in large measure to the collaboration between the black realtor, Archie Givens, and the homebuilder, Edward Tilsen, who constructed a series of affordable homes for blacks along a corridor from 42nd to 46th Streets on 3rd, 4th, and 5th Avenues. In 1956, my father and mother moved into one of those Tilsenbilt homes on the 4200 block of 4th Avenue. That same year, my father built a house for his mother and grandmother at 326 East 45th street. Other families that started moving south of 42nd at that time were the Boudreaux’s who were at the corner of 42nd Street and 4th Avenue, and the Wilsons at 43rd Street and 3rdAvenue. The Kippers moved to the 4500 block of Oakland in 1957. This was effectively an extension of the older black Southside community, given that so many of those who started moving south of 42nd, such as the Bowman, McMoore, Webster, Mays, and Kay families, had grown up in the Bryant neighborhood. Regina High School had not been built, when the movement south began, but eventually the neighborhood would come to be called the Regina-Field neighborhood.”

I lived across the street from the Bowmans and on the same side of the street as the McMoores, a few houses down. I attended elementary school with Scott Mays at Field Elementary, which had only integrated a few years earlier amid significant protests by white families. Civil rights battles were unfolding all around me; my elders were conducting the struggle, and I was merely a beneficiary.

When I was twelve, it wasn’t unusual to play outside with my friends after school. On Thursday, April 4, 1968, we were playing basketball in Mark Mitdahl’s driveway when my mother ran down the alley calling me. I’d never seen her run before. Mark’s house was near the end of our block, and when she got close enough, she told me to come home right away. I started walking toward her, but she told me to move faster. When I reached her, she told me I wasn’t in trouble, but I had to come home right away. When we arrived, she sat in front of our recently obtained color TV and started crying. Martin Luther King had been assassinated, I did know who he was.

My first activism began in my high school years. I attended Marshall University High School from grades 8–12. M-U High was unique in that it was the only public school in Minneapolis covering grades 7–12. That came about because of a merger between the private University High, which covered those grades, and the public Marshall High, two blocks away. I attended University High in 7th grade, located on the University of Minnesota's campus. I saw daily protests about the Vietnam War. I remember joining a march from the University campus, across the bridge spanning the Mississippi River to downtown. As I approached draft age and the war was in the news daily, I developed a keen interest in Vietnam's politics. Like Muhammad Ali, I didn’t have any quarrel with the North Vietnamese.

“I ain’t got no quarrel with them Viet Cong”-Muhammad Ali

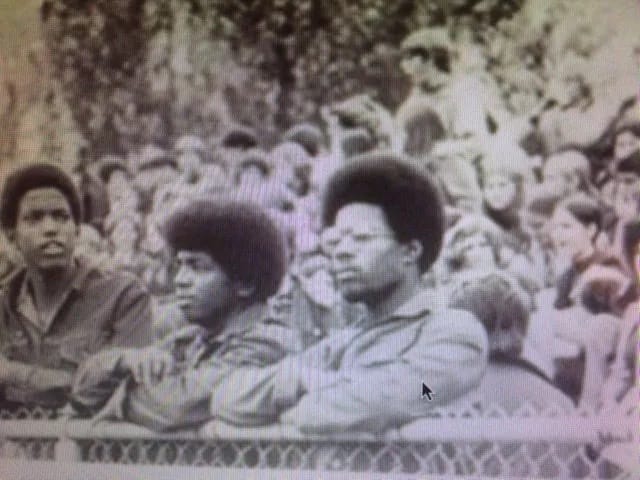

M-U High became more integrated as the consent decrees took effect. M-U had been the first high school in Minneapolis to integrate voluntarily. By my junior year, we received buses of Black kids from North Minneapolis. The couple of dozen Black kids from South Minneapolis, like me, either took the city bus or got rides from their parents.

I had grown up attending Zion Baptist Church as long as I can remember. Not long after my baptism, the church moved to a new location in North Minneapolis. While in high school, I attended a National Sunday School Baptist Training Union (BTU) Conference in Little Rock. Arkansas. As part of that trip, we stood on the steps of Little Rock Central High School. It was quiet on the day we went. Only later did I read of what happened where I was standing.

Until I attended Fisk University in the fall of 1973, I had learned very little about Black history. We had Black History Week at M-U High, though it seems we reviewed the same things every year. The focus was on Booker T. Washington, Rosa Parks, and Benjamin Banneker. We briefly reviewed Toussaint Louverture and the Haitian Revolution, but never the revolts on American soil. We never studied Nat Turner, Gabriel Prosser, or Denmark Vesey. I point to a single moment in time as the awakening of my lifelong interest in Black history. As a freshman, I played varsity basketball, and on a road trip to Fort Valley, GA, we drove on a two-lane state highway with peach groves on both sides of the road. I was amazed at how perfect the rows seemed.

On the right side, the peach grove ended, and acreage of another crop began. Thigh-high bushes with white balls I didn’t immediately identify. It sunk in that I was looking at a cotton field and feeling I didn’t know I had stirred inside me. Our road trips were usually filled with joking between teammates, but I fell silent, wondering about those who came before and what they had endured. I became painfully aware of how much I did not know. That day, it became my mission to learn more.

Check back for the second part of William Spivey's I Fought for Civil Rights and All I Got Was Juneteenth

This post originally appeared on Medium and is edited and republished with author's permission. Read more of William Spivey's work on Medium. And if you dig his words, buy the man a coffee.