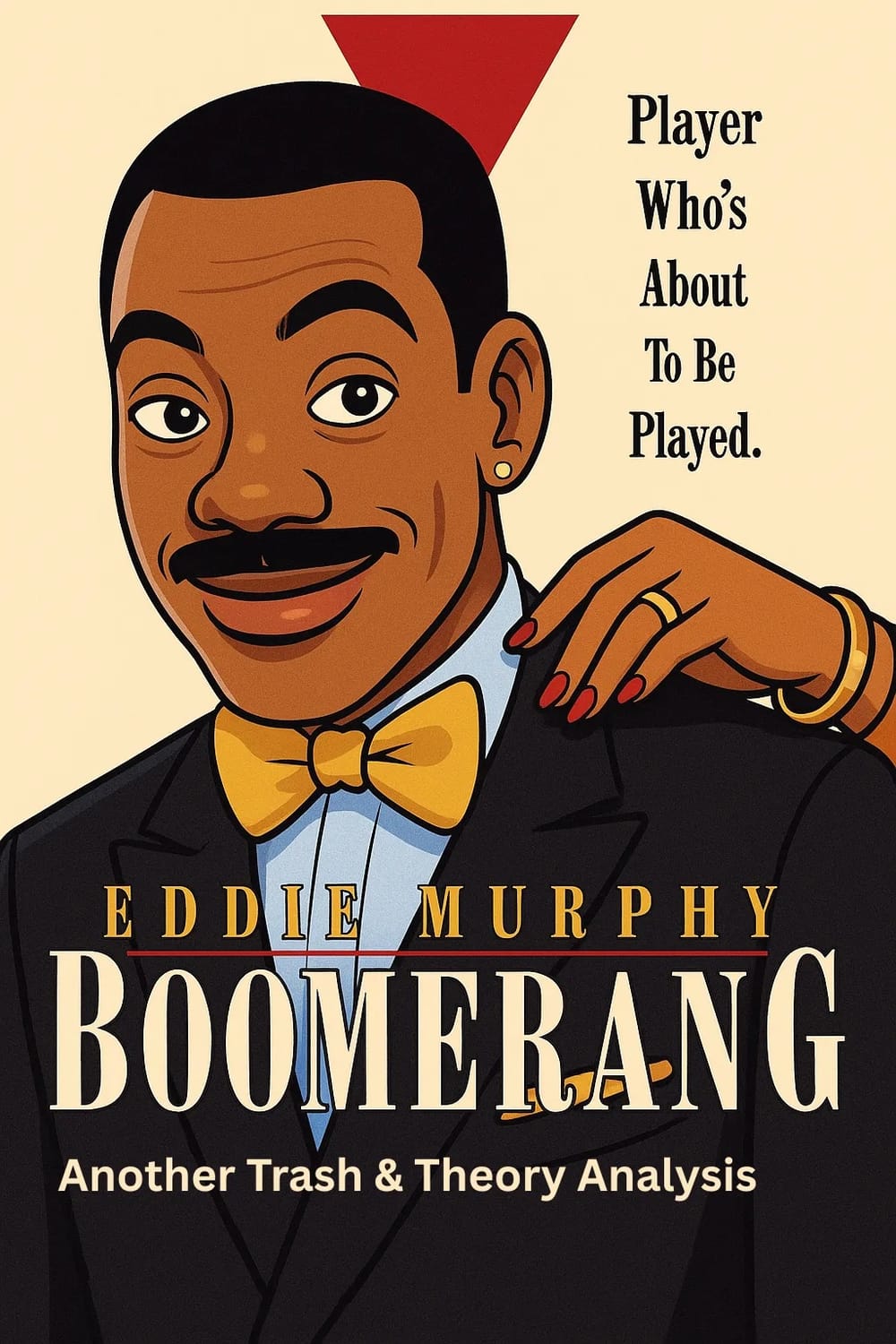

Marcus Graham was every Black woman’s crush and every Black man’s excuse. He was a literal walking cologne commercial in every sense; A well-dressed executive who treated seduction like a skill set. If you were alive in the 90s, you knew a Marcus well. Hell, some of y’all dated a Marcus, but that’s another topic for another day.

Boomerang wasn’t just a romantic comedy but a social study dressed in Armani. And somehow, witnessing the moment the Black elite got its cinematic glow-up came with the same old gender politics with better shoes.

Because beneath the champagne, corporate chic, and smooth jazz soundtrack lies a truth we still haven’t outgrown: Black women can be desirable, powerful, or respected, but are rarely allowed to be all three at once.

The Black Corporate Fantasy

The early ‘90s were obsessed with image rehab. After a decade of Reaganomics and cultural caricature, Hollywood needed a new face for Black success: polished, educated, and corporate.

Boomerang was aspirational propaganda. It said, “We’ve made it, can wear designer clothes now, and we’re not just working in the building; we own the damn floor.”

Eddie Murphy’s Marcus Graham embodied that new prototype: confident, wealthy, hyper-articulate, and allergic to accountability. The film treats his womanizing like a character quirk: something charming, even enviable. His success in his career becomes both shield and justification.

But here’s the plot twist: in a culture obsessed with breaking free from white stereotypes, Boomerang quietly reinforced a new one: that professional achievement equals emotional maturity…or at least, that’s the expectation. But Marcus had the wardrobe of a CEO and the emotional depth of a brutish fragrance ad.

Enter Robin Givens’ Jacqueline: all sleek power and sexual autonomy. She’s everything Marcus thinks he wants until she starts acting just like him. Then suddenly, it’s a problem.

Jacqueline doesn’t chase, beg, or nurture; she simply enjoys Marcus and moves on. There is no drama, no apology, and certainly not one lick of emotional aftercare.

For the first time, Marcus becomes the prey, and his ego simply cannot process it. The film forces him (and the audience) to feel what women feel every time they’re reduced to a body or an experience.

But even as Jacqueline embodies equality on paper, the film punishes her for it.

Her independence is reframed as coldness, and her success becomes arrogance. She’s not allowed to be both powerful and loved. So, although she has almost everything, her innate flaw is that her career aspirations have turned her cold, and she will step on anyone to get where she wants to go.

That’s the real boomerang: when a woman mirrors a man’s behavior, she’s not celebrated; she’s condemned. So, although a few of us were cheering in the stands when he got his just desserts, the overarching morale was that it was bad to be like Jaqueline.

Then comes Halle Berry’s Angela: the artistic, gentle, emotionally intelligent woman, that is, his Angel on earth. *gags*

She’s written as the antithesis of Jacqueline in virtually every way: soft, forgiving, and nurturing af. She paints, listens, absorbs, and truly shows Marcus how love feels in action.

Eventually, she becomes the reward for finally feeling feelings like a real boy. We’re all so impressed.

The film treats Angela like moral medicine. She’s the woman who helps the man “heal” after he’s done breaking others. Her love is his redemption arc.

But let’s be real: it’s not love, it’s labor. Angela is written as the emotional rehab center for Marcus’s ego. She doesn’t challenge him; she repairs him. Sure, she leaves after he reveals himself to be the narcissist he likely is, but all it took to get her back was a couple of artsy kids and a visit to her new office. And by the end, we’re supposed to clap because he finally chooses the “good one.”

The Politics of Desire

Boomerang’s brilliance is that it disguises all this under comedy and sex appeal. But when you strip the jokes away, the film’s love triangle reads like a cultural blueprint:

- Jacqueline’s desire equals dangerous, masculine, and unnatural.

- Marcus’s desire equals expected and even charming.

- Angela’s desire equals safe, motherly, and redemptive.

That’s the hierarchy of desirability the 90s handed us; one we still carry. Black women were expected to choose a lane: be sexy but submissive, ambitious but alone, loving but unthreatening.

Even within Black affluence, the same gender politics followed.

Jacqueline had power, but not softness. Angela had love, but no agency.

And then there's the supporting characters. I’d be remiss if I didn’t get into some of the colorism. For instance, Helen Strangé, who is played by Grace Jones, is like Jaqueline on steroids. She almost blows her entire deal because she’s upset that Marcus won’t sleep with her, and of course, she’s played by a dark skinned woman. On the other hand, the Elderly Lady Eloise, played by Eartha Kitt, was a hypersexual elderly woman whom Marcus actually sleeps with to secure the bag…or so he thought. Also, Christie, played by Lela Rochon, is a lighter-skinned airhead who is easily manipulated.

The only slight variation from the norm in terms of these tropes occurs with his obsessed neighbor, Yvonne, who seems to live to meddle in his affairs but also readily offers him access to her vagina, which he has tried but is no longer interested in. Nevertheless, this seems to be a commentary on his “roster” more than an indication of their value. In other words, even his throwaways are baddies.

Fast forward to now: the Marcus archetype is still thriving.

He’s in a fitted tee, calling himself “high-value.”

He’s trading crypto, ghosting women, and still confusing healing with a rebrand. The Jacqueline archetype still gets labeled “too independent,” and the Angela archetype still gets drained and applauded for it.

We call it “modern dating,” but it’s just the same script with new filters. Boomerang taught men to evolve just enough to keep access, not enough to share power. And that’s the biggest full-circle moment of them all.

At the end of the day, Marcus apologizes, Angela forgives, and Toni Braxton’s love songs play like a choir selection.

But here’s the thing: maybe love did bring him home.

Just not to her. Instead of the boomerang being his karma in relationships, the real full circle moment was Marcus finally facing his own reflection. Because Boomerang wasn’t about love at all; it was about accountability and how rarely men survive without a woman cushioning the fall.

This post originally appeared on Substack and is edited and republished with author's permission.