To those who read the subtitle and had no clue what the Tribal College Program (sometimes called 1994 Institutions) and HSACUs (Hispanic Serving Agricultural Colleges and Universities) are, think of them and HBCUs as a half-hearted attempt to educate those not otherwise welcome in PWIs (predominantly white institutions). The photo is of the current administrative building at Fisk University, my alma mater. I chose Fisk because I always choose Fisk; it’s what I do.

The HBCUs came first, starting with Cheney University in Pennsylvania in 1837. Then came The University of the District of Columbia in 1851, Lincoln University -Pennsylvania in 1854, Wilberforce University in 1856, Lemoyne-Owen in 1862, Virginia Union in 1864, Bowie State, Atlanta University (now Clark-Atlanta University, or Shaw University in 1865 after the Civil War ended, and several Black colleges in 1866, including Fisk University, Lincoln University of Missouri, and Rust College. Most of them had different names, like The African Institute, Miner College, Fisk Free Colored School, The Ashmun Institute, and more, before becoming what they are today.

All of them were initially private institutions, though Lincoln of Missouri received $5,000 in state funding to train Black teachers. Most began with different names, and none resembled the colleges and universities they are today. While some goodwill was undoubtedly intended, all came into being because white people generally didn’t want their kids attending school with Black ones.

Next came the Tribal College Program. It should be noted that the distinction between the first private HBCUs and the Tribal College Program is significant. There were the Morrill Land Acts of 1862 and 1890. The first Act allocated 17,400,000 total acres to initially fund sixty-nine colleges, including Auburn University, the University of California, the University of Florida, the University of Georgia, Purdue University, the University of Kentucky, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), Michigan State University, the University of Minnesota, Rutgers, Cornell, and Ohio State University.

None of them were HBCUs or tribal colleges. Native Americans weren’t mentioned unless you count the “unassigned Federal lands” that belonged to them, which financed the institutions. The Morrill Land Act of 1862 was the biggest land grab in US History, stealing from the red man to benefit white men.

In 1890, the Second Morrill Land Act provided cash instead of land to create new schools. This Act was intended to be non-discriminatory and included funds for seventeen Black colleges and universities, including Alabama A&M University, Tennessee State University, Tuskegee University, and Fort Valley State University. Even though the Act required a dollar-for-dollar distribution to HBCUs and white institutions, the cash these Black colleges received was far less than what the Primarily White Institutions (PWIs) received. This imbalance remains real under the individual state governments that sponsor the schools.

In 1994, a third land grant bill was passed, which funded some twenty-nine tribal colleges (now expanded to thirty-four). Those schools include Saginaw Chippewa Tribal College, Red Lake Nation College, Sitting Bull College, Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribal College, and Little Big Horn College. The US Department of Agriculture brags about how effectively the schools have educated Native Americans. One might look at the creation of these schools as a mere pittance compared to the original seventeen and a half million acres taken from Native Americans.

It was 2008 before the Food, Conservation, and Energy Act of 2008 (FCEA) authorized the establishment of a group of Hispanic-serving agricultural colleges and universities (HSACUs) to be eligible for NIFA Integrated Research, Education, and Extension Competitive Grants Programs. Schools are approved for HSACU funding on an annual basis and are primarily PWIs, and a few HBCUs that meet the criteria, including a minimum of 25% Hispanic enrolment and 15% of degrees awarded in agricultural fields, go to Hispanics. I understand the need for focusing on agriculture in 1862, not so much directing Hispanics into agriculture in 2008.

Hispanic-Serving Agricultural Colleges and Universities (HSACU) | NIFA

The states distribute the funds in the public school or state school sector and have always favored the PWIs. Maryland reached a $577 million settlement after fifteen years of battling a federal lawsuit to address the underfunding. North Carolina has started providing additional funds to its HBCUs in recognition that federal action and lawsuits lie ahead.

The Second Morrill Act of 1890 required a dollar-for-dollar distribution to HBCUs vs. their white counterparts. Only Delaware and Ohio have complied. The Hunt Institute released a report showing the overall funding deficit approaches $13 Billion. Here’s the breakdown by state.

- North Carolina: $2.76 billion

- Florida: $1.94 billion

- Louisiana: $1.37 billion

- Texas: $1.08 billion

- Georgia: $577.2 million

- West Virginia: $504 million

- Arkansas: $457.5 million

- Alabama: $437.3 million

- South Carolina: $424 million

- Maryland: $416.6 million

- Oklahoma: $367.7 million

- Mississippi: $306.3 million

- Virginia: $147.7 million

- Kentucky: $1.66 million

- Missouri: $109.5 million

The Biden administration sent 16 governors letters asking them to address the underfunding. Attorney Ben Crump has threatened Tennessee with a lawsuit unless Tennessee State University gets back the $2.1 billion in underfunding over the years. In the late 1970s, Tennessee merged two state institutions in Nashville, Tennessee State University (TSU) and the much smaller University of Tennessee-Nashville (UTN). It was feared that TSU would lose its HBCU identity, which didn’t happen. TSU lost in other ways by receiving less funding than the University of Tennessee and other state schools in Tennessee. Tennessee acknowledges some underfunding and allocated $250 million as what they consider a “good faith effort” to make TSU whole.

Private schools don’t receive federal funds in the same way but are eligible for research grants from government agencies, including the National Institute of Health (NIH) and the National Science Foundation (NSF). Private schools also receive student financial aid, work-study grants, and veterans' benefits, and can participate in federal partnerships. Ask yourself if private HBCU Fisk University in Nashville gets the same level of federal funding as nearby Vanderbilt University, which was founded seven years later. The DOGE cuts to research grants to PWIs may be the first time the trickle-down economic theory works. Cuts to Harvard et. al. are hurting HBCUs as well.

HBCUs, the Tribal College Program, and HSACUs have never received the funding required to fulfill their purpose, sometimes violating federal law. Maryland, North Carolina, and Tennessee have taken steps, however small, to address the issue. The official response from Florida is to deny any underfunding and praise the funding for FAMU, one of the 1890 Morrill Act schools.

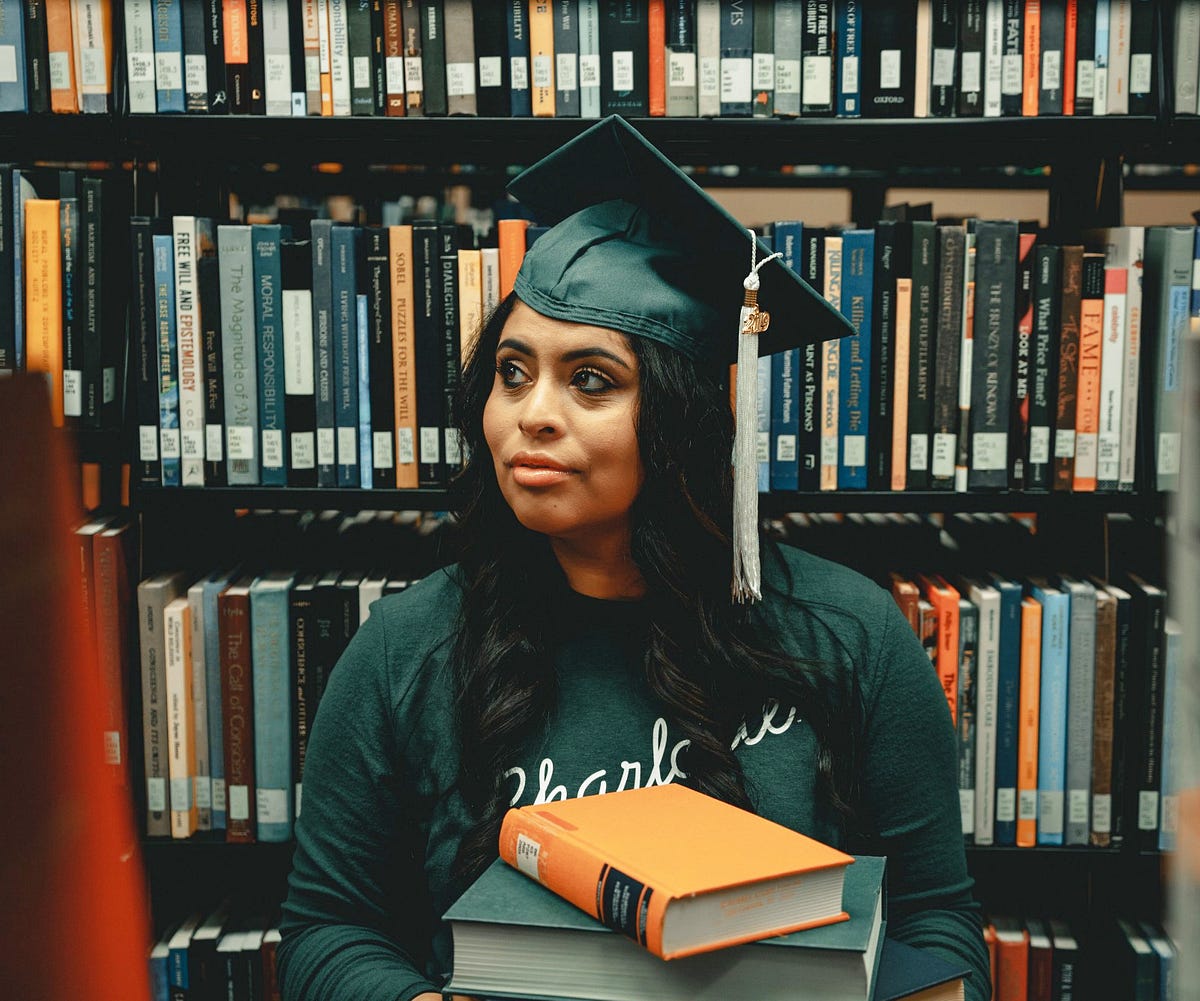

I suspect more states will respond, like Florida, than Maryland. I further predict that before these states make HBCUs whole, they will try eliminating them with mergers, claims of duplication, and cries of reverse discrimination. They will cling tighter to their money than the NRA does to their guns. Meanwhile, HBCUs are serving more diverse populations than ever. Imagine if they had the same facilities and programs as their PWI counterparts.

This post originally appeared on Medium and is edited and republished with author's permission. Read more of William Spivey's work on Medium. And if you dig his words, buy the man a coffee.