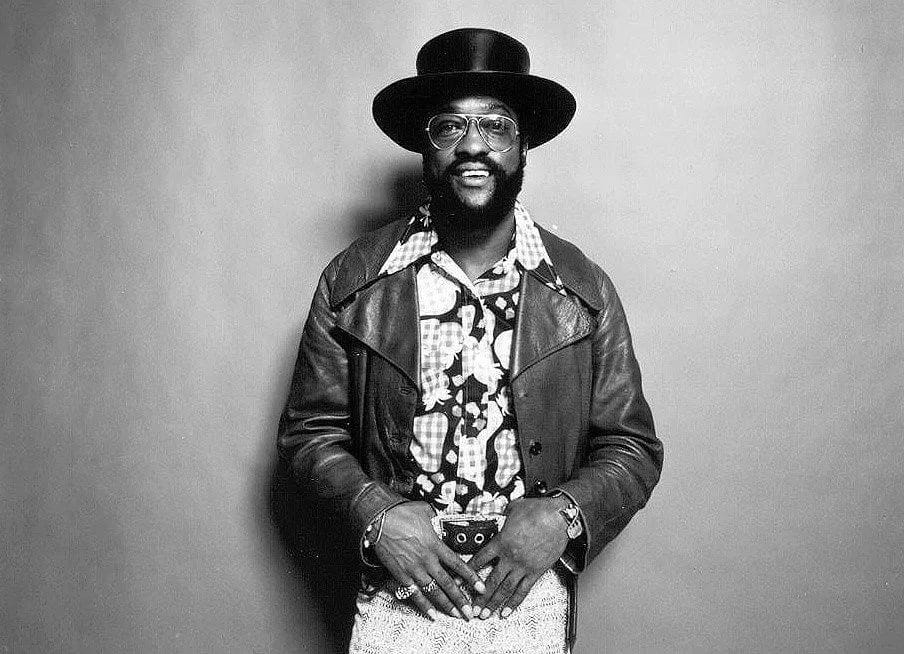

Billy Paul was a grown man of 37 years-old when he registered his first and only Pop hit with the classic “Me and Mrs. Jones.” But to think of Paul as a “one-hit wonder” is to misread his influence and legacy. Paul was the very foundation of the iconic Philly Sound of the 1970s, bridging the region’s Jazz traditions with the burgeoning aspirational Soul and Dance music that producers Kenneth Gamble and Leon Huff became most recognizable for.

When Gamble and Huff were tapped by Clive Davis and CBS records to create a Black boutique label to compete with Motown and Stax, the duo often leaned on seasoned talent. Billy Paul, Harold Melvin and The Bluenotes, and The O’Jays — who all logged the first Gold singles for the new label — were all veterans of the industry, who had worked with Gamble and Huff prior to the launch of Philadelphia International Records (PIR) in 1971.

Gamble and Huff had long known Paul to be an agile and adept interpreter of Jazz and Pop standards. As Paul told the Los Angeles Sentinel in 1973, “[Gamble and Huff] know me, they know what I do best” and what Paul did best was reinterpret an expanded American songbook On the albums Feelin’ Good at the Cadillac Club (Gamble Records, 1968) and Ebony Woman, produced by Gamble and Huff in 1970, Paul covers Sinatra’s “That’s Life,” West Side Story’s iconic “Somewhere” and what might be a definitive cover of Nina Simone’s signature “Feeling Free.” Billy Paul was never intended to drive the Soul Train, as it were, but rather be the steady album producer that would help Gamble and Huff attract and maintain a mature Black audience, as young folk flocked to the Funk and Disco dancefloors.

Paul’s Going East (1971) was the very first album released on Philadelphia International Records. On the obscure classic, Paul offers jazz covers of Steppenwolf’s “Magic Carpet Ride” and Eugene McDaniel’s “Compared to What?,” and a simply beautiful rendition of Jimmy Webb’s “This Is Your Life,”; Paul closes the album with the Gamble and Huff ballad “Love Buddies” — surely for the grown and sexy — and Rodgers and Hart’s “There a Small Hotel.” On the album’s back jacket, Going East is introduced by vocalist Nancy Wilson, who recorded close to 70 albums between 1959 and 2006, largely filled with interpretations of the American Songbook, producing only two singles that broke into the top 20.

“Me & Mrs. Jones” topped the Pop charts for three weeks in December of 1972, displacing Helen Reddy’s feminist anthem “I Am Woman.” To be sure, the song, written by Gamble, Huff, and Cary Gilbert, was a classic, but it was Paul’s signature vocal style that also resonated with audiences. In an era when many of Paul’s Soul peers were punching notes as if making some emphatic statement about Black masculinity, his was a style that nimbly caressed notes. Paul’s distinctive vocal style was premised on his ability to sing naturally in a higher vocal register, without the use of falsetto.

Paul noted that his emotive style was largely influenced by Black women singers such as Nancy Wilson, Nina Simone, Carmen McRae, though he also mentioned Billy Stewart and Jimmy Scott as inspirations. “I developed my own phrasing, especially from female singers because they could sing high range without falsetto,” Paul told the Bay State Banner in 1978.

But Paul also recalled conversations with John Coltrane when both were cutting their teeth in the Philadelphia Jazz scene in the 1950s: “So in my case, that meant singing like a horn player. I’d always been a John Coltrane fan — he was from Philly; you know, and he told me once he wanted to be a singer and that’s why he played the way he did. Well, I sang the way he blew after what he said, and I knew it was right.”

The success of “Me and Mrs. Jones” presented a quandary for the new label, as to the best follow-up single. The label’s choice “Am I Black Enough For You?” written by Gamble and Huff, famously stalled at #73 on the Pop charts. As John A. Jackson writes in his fine social history of Philly Soul, the song was “a defiant paean to black pride and resolve” adding that “the relentless refrain of the song’s title ‘Am I Black Enough for You?’ would not endear itself to the massive white audience that awaited Billy Paul’s next release.” (A House on Fire: The Rise and Fall of Philadelphia Soul).

With “Am I Black Enough for You,” Billy Paul embodied what would be the on-going tension at Philadelphia International Records, that of being able to sell records to a broad mainstream audience, while still articulating Gamble and Huff’s calls for Black progress and self-determination; how to shake asses like Motown and commit publicly to Social Justice in a manner like Al Bell’s iteration of Stax. Labelmates The O’Jays somehow found that middle ground as Ship Ahoy, which included the hit single “For the Love of Money,” gave a knowing nod to the Transatlantic Slave Trade.

Billy Paul would never again be a viable crossover artist. None of Paul’s albums charted higher than #88, and only one of his singles would even hit the top 10 on the R&B charts. Yet, more than any artists on the label, Paul was the primary vehicle for Gamble and Huff’s most strident — and controversial — political messages. Indeed, one of the most poignant tracks on 360 Degrees of Billy Paul, “I’m Just a Prisoner,” anticipates commentary on the “New Jim Crow,” doubling down on Philadelphia International’s mantra “The Message is in the Music.”

Paul’s “Black Wonders of the World” (Got My Head on Straight, 1974), for example, aggregates two centuries of Black American history over the course of eight minutes. “Let ’Em In,” Paul’s 1976 cover of Paul McCartney and Wings hit, opens with a sample from Malcolm X’s “hoodwinked” speech, and surely must be the first pop recording to feature the leader’s voice; the message became a prominent feature of Billy Paul’s albums. As Paul reflected around the time of the release of War of the Gods, “Whites have always been into albums…but now Blacks are into albums…It’s been like that…especially after Marvin Gaye came out with What’s Going On.” (Chicago Defender, 1973).

As such the highlight of Billy Paul’s career at Philadelphia International Records was When Love is New (1975). Side one of the album features dance tracks that celebrate the power of Black community (“People Power”), implores the United States to live up to its ideals on the eve of the Bicentennial (“America (We Need the Light)”), and highlights the influence Black consumer spending (“Let the Dollar Circulate”).

Yet ironically, it was the album’s second side, filled with stellar ballads like “I Want Cha’ Baby” — pound for pound, one of the best “Quiet Storm” songs from the era — and the timeless “When Love is New” that generated the most controversy. The three-song suite of the second side was closed by “Let’s Make a Baby,” a stepper number, that a few skittish Black radio stations were ambivalent about playing because of its so-called “obscene” title and theme. The song’s messaging was part of Gamble and Huff’s on-going push for stable, patriarchal Black families, as Gamble wrote on the back jacket of When Love is New, “Let’s keep making babies so we can have a great, beautiful, righteous, meek, but strong nation.” Never before has an anti-Choice message been rendered so soulfully.

By the time Paul released First Class (1979), his final album for PIR, the label itself was only a skeleton of itself, with the breakout solo success ofTeddy Pendergrass keeping it above water. As he prepared for the recording of First Class, Paul told the Bay State Banner “You pay dues for not sounding like everybody else, but then what good is being a star? What happens when your life as a star is over?…the bottom line is your musicianship if you want to survive, so I shape my singing around how I feel about the music.”

Paul recorded a few more albums for major labels through the 1980s, and continued to tour throughout his life, releasing several live recordings on his own label. Billy Paul might have taken one for the team, in the aftermath of “Me & Mrs. Jones,” but his contributions to the tradition of vibrant and sophisticated Soul music will be a reminder that not all sacrifices are for naught.

Mark Anthony Neal is the James B. Duke Distinguished Professor of African American Studies and Professor of English and Gender, Sexuality and Feminist Studies at Duke University. The author of several books including Looking for Leroy: Illegible Black Masculinities and Black Ephemera: The Crisis and Challenge of the Musical Archive, both from NYU Press. His next book Save a Seat for Me: Meditations on Black Masculinity and Fatherhood will be published by Simon & Schuster.

This post originally appeared on Medium and is edited and republished with author's permission. Read more of Mark Anthony Neal's work on Medium.