Jesse Jackson passed away yesterday at his Chicago home. He was 84.

Jackson is typically associated with Chicago, but he grew up in the South, born and raised in Greenville, South Carolina. He attended segregated Sterling High School, where he was elected class president and lettered in three sports. Perhaps that why he spoke is sports analogies. Jesse accepted a football scholarship at the University of Illinois. While home on Christmas break, he needed a book from the whites-only public library and was denied access because he was Black. Six months later, on July 16, 1960, he and seven other students staged a sit-in. They were all arrested and became known as the Greenville Eight. Two months later, the library was desegregated. Jackson is also associated with Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., but got his start in the civil rights movement well before meeting Dr. King.

Jackson transferred to North Carolina A&T, where he continued his education and organizing. He graduated in 1964 with a B.S. in Sociology, moving to Chicago immediately afterward to attend the Chicago Theological Seminary. My friends in Omega Psi Phi Fraternity, Inc., wouldn’t forgive me if I didn’t note his membership in that fine organization.

Jackson became involved with Dr. King through the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). While studying at Chicago Theological Seminary, he organized students to join the Selma voting‑rights campaign in 1965, then asked Ralph Abernathy for a staff role. King took a chance and hired him into SCLC. By 1966 Jackson was leading SCLC's economic-justice arm, Operation Breadbasket, and quickly became part of King’s inner circle. Jesse left the Seminary three classes short, compelled to focus full-time on the civil rights movement. He never returned to the Seminary but was granted an honorary degree in 1972, one of more than 40 he would receive in his lifetime.

When Jackson joined the Southern Christian Leadership Conference in 1965, he quickly became one of the most visible young organizers in the organization. As Operation Breadbasket's lead, Jackson was in charge of pressuring major corporations to hire Black workers, open contracts to Black businesses, and invest in Black communities. Jackson ran negotiations, organized boycotts, led Saturday morning rallies in Chicago, and became the public face of SCLC’s northern economic campaigns. These are the skills that would serve him well later in life at Operation PUSH (People United to Save Humanity).

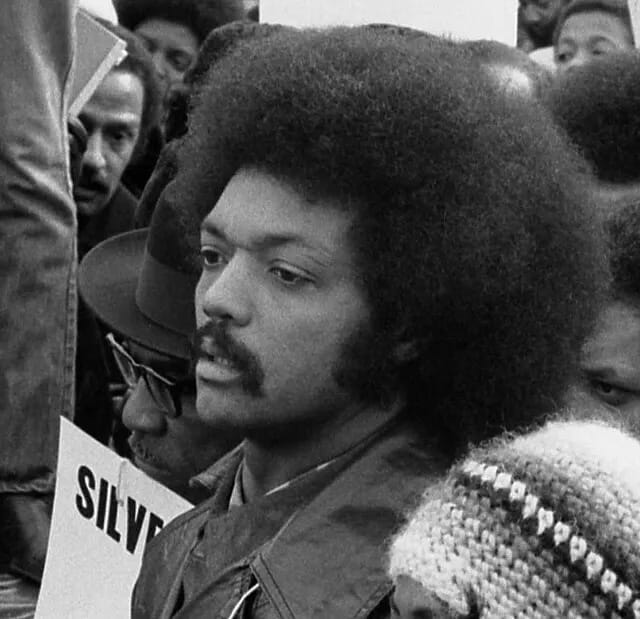

Inside the organization, Jackson was known for his energy, charisma, and ability to mobilize crowds — qualities King valued even when they created tension with older, more traditional SCLC staff. By 1967–68, Jackson had become one of the most recognizable SCLC figures after King and Ralph Abernathy, and was physically present with King in Memphis during the sanitation workers’ strike.

Jackson was in his mid‑20s when he entered King’s orbit — extraordinarily young for a national civil‑rights leadership role. In 1966, MLK was 37, Ralph Abernathy was 40, Andrew Young was 34, Hosea Williams was 40, and James Bevel was 29. Jackson turned 25 late in the year. That age gap mattered in an organization built on seniority, clergy hierarchy, and long years of movement experience.

Several factors fed the resentment folks had for him. King put Jackson in charge of Operation Breadbasket within a year of meeting him — a level of responsibility that most staff had waited a decade to attain. Jackson was a gifted speaker and crowd‑builder. Older SCLC staff sometimes felt overshadowed by a newcomer who hadn’t “paid the same dues.”

Jackson’s approach was more theatrical, media‑savvy, and youth‑driven. Many SCLC veterans preferred King’s quieter, pastoral style. King saw Jackson as a bridge to younger activists and northern cities. That trust amplified internal friction. Whether fair or not, several SCLC leaders believed Jackson was positioning himself for national leadership before he was ready.

After King’s assassination in 1968, Jesse Jackson’s position inside the SCLC became more visible and contested. In the immediate aftermath, he emerged as one of the most recognizable figures associated with King’s final hours, which drew national attention and made him a symbolic link to the movement’s future. But within the SCLC, his role did not expand as the public assumed it would. Instead, tensions that had been simmering before Memphis — generational divides, personality clashes, and disagreements over strategy — intensified.

Ralph Abernathy succeeded King as SCLC president and expected Jackson to remain under his authority. Jackson, however, believed the movement needed a new direction rooted in economic empowerment and northern organizing. The friction between them grew until Jackson resigned in 1971 and founded Operation PUSH, an independent organization that reflected his own vision of Black political and economic power.

The friction within the SCLC and the civil rights movement had plenty of help. The SCLC was one of the primary targets of COINTELPRO’s “Black Nationalist Hate Groups” program. The FBI wiretapped SCLC offices and staff, monitored King’s travel, speeches, and private life, planted informants inside the organization, attempted to sow distrust between King, Abernathy, Bevel, and younger figures like Jackson, and leaked disinformation to the press. The goal was to neutralize King and destabilize the SCLC as a national force.

After King’s death, the FBI did not stop monitoring the SCLC. Instead, the focus changed. Ralph Abernathy’s leadership was surveilled. The FBI tracked his Poor People’s Campaign, Resurrection City, and his attempts to keep the SCLC unified.

Jackson became a new focal point. Because he was young, charismatic, and gaining national visibility, the FBI monitored his activities closely — especially the formation of Operation Breadbasket and later Operation PUSH. The Bureau continued to feed narratives of rivalry between Jackson and Abernathy, hoping to weaken the organization from within.

When Jesse Jackson launched Operation PUSH (People United to Save Humanity) in 1971, he created an organization that immediately filled the vacuum left by the post‑King fragmentation of the SCLC. PUSH became a national force almost overnight because Jackson understood something the older civil‑rights institutions had not yet adapted to: the next phase of Black freedom work would be economic, not just legislative.

In its first years, PUSH ran “Buy Black” campaigns, negotiated with major corporations for hiring commitments, opened doors for Black-owned businesses, and held weekly Saturday morning meetings that blended political education, worship, and media spectacle. Jackson’s charisma turned these gatherings into must‑attend events for Chicago politicians, national reporters, and corporate executives who suddenly found themselves answering to a new kind of accountability. By the mid‑1970s, PUSH had secured millions of dollars in corporate pledges, job programs, and contracts — a level of economic leverage no other civil‑rights organization had achieved since King’s death.

It worked to Jackson’s benefit that COINTELPRO was exposed in March 1971, when activists broke into an FBI field office in Media, Pennsylvania. They stole files documenting COINTELPRO operations. Those files were mailed to journalists and members of Congress. The Washington Post published the first major exposé. The scandal forced Hoover to declare the program “ended” later that year. Operation Push and Jackson had a brief honeymoon period that wouldn’t have happened had COINTELPRO been operating at full speed. The program would later reinvent itself in search of Black Identity Extremists, but there was a moment of respite.

That doesn’t mean there was no pushback against Jackson’s success with Operation Push. Some corporations fought back against being pressured to hire more Black people and work with minority contractors. There was rebellion against the success of the civil rights movement, which included the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the Voting Rights Act of 1965, and the Fair Housing Act of 1968. Kentucky basketball integrated in 1969 and Alabama football in 1971 after USC humiliated them using Black players at Legion Field in Birmingham. Not everyone was happy with the progress of civil rights, and Jackson was one of the most visible remaining leaders, after Malcolm X and Martin Luther King, Jr. had been taken off the board.

Politically speaking, the Southern Strategy was in full effect and shaping Republican messaging and electoral maps. Jackson’s response was to run for President in 1984 and 1988. Jackson’s 1984 run was the first truly viable presidential campaign by a Black American in a major party primary, though his success couldn’t have happened without Shirley Chisholm running before him.

In 1984, Jesse’s measurable successes included:

- 3.5 million votes nationwide

- 5 primary wins (including D.C. and Louisiana)

- 21% of the total primary vote

- A major expansion of Black voter turnout

- Forcing the Democratic Party to confront issues of poverty, apartheid, and urban disinvestment

He didn’t come close to winning the nomination, but he changed the electorate and proved that a Black candidate could compete nationally.

Jackson’s second run in 1988 was dramatically more successful.

He won:

- Nearly 7 million votes

- 13 primaries and caucuses

- Second place overall behind Michael Dukakis

- Major victories in states like Michigan, where he won a broad multiracial coalition

By 1988, Jackson wasn’t a symbolic candidate — he was a serious national contender who finished ahead of several mainstream Democrats.

His 1988 campaign forced the Democratic Party to:

- Expand proportional delegate rules

- Recognize the political power of Black, Latino, and poor voters

- Integrate more diverse voices into the party’s leadership structure

Many historians argue that Jackson’s 1988 coalition laid the groundwork for later multiracial, progressive presidential coalitions. Without the proportional delegate rule change, Barack Obama wouldn’t have been able to win the Democratic Nomination and become America’s first Black President.

Jackson’s 1988 campaign was the high‑water mark of his national political influence. He won millions of votes, carried major states, and finished second in the Democratic primaries — the strongest showing by a Black presidential candidate up to that point.

That success frightened and angered multiple power centers, and the pushback was immediate. Here's how Jackson's power crumbled:

1. Democratic Party Establishment

Jackson’s multiracial “Rainbow Coalition” threatened the party’s traditional hierarchy.

After 1988, key Democratic strategists and donors:

- worked to limit Jackson’s influence on the party platform

- resisted his push for proportional delegate reforms

- marginalized him in internal decision‑making

- elevated “New Democrat” centrists as a counterweight

Jackson’s rise was seen as a challenge to the party’s control over its own direction.

2. Conservative Media and Political Operatives

Right‑wing media and Republican strategists portrayed Jackson as:

- radical

- dangerous

- unpatriotic

- economically unrealistic

This wasn’t about Jackson personally — it was part of a broader effort to demonize Black political power emerging from the civil‑rights generation.

3. Corporate Interests

Jackson’s platform targeted:

- corporate consolidation

- discriminatory lending

- redlining

- apartheid‑linked investments

- labor exploitation

His economic agenda threatened entrenched interests, and corporate lobbying groups worked to undercut his influence in both parties.

4. Segments of the Democratic South

Jackson’s success in states like Michigan and the Deep South alarmed white Southern Democrats who feared:

- a shift in party power toward Black voters

- the rise of a new progressive coalition

- the erosion of their regional influence

This bloc worked quietly but effectively to block Jackson’s ascent within the party.

5. Internal Movement Tensions

Even within the civil‑rights community, Jackson’s prominence created friction.

Some older leaders:

- resented his national visibility

- questioned his political ambitions

- feared he was overshadowing the legacy of King

These tensions didn’t destroy his influence, but they complicated his ability to consolidate power after 1988.

6. Intelligence and Law‑Enforcement Scrutiny

While COINTELPRO had officially ended in 1971, surveillance of Black political leaders did not.

Jackson’s rising national profile in the 1980s drew:

- increased monitoring

- political vetting

- media leaks

- attempts to discredit him

After 1988, the Democratic Party leadership embraced a new ideological direction — the rise of the “New Democrats” and the Democratic Leadership Council (DLC). Their strategy emphasized:

- suburban moderates

- business‑friendly policies

- distancing the party from its civil‑rights era identity

Jackson’s Rainbow Coalition — multiracial, poor, urban, labor‑aligned — no longer fit the party’s strategic blueprint. His influence inside the party structure shrank as the DLC gained dominance.

7. Media Attention Shifted to New Faces

By the early 1990s, national media attention moved toward:

- Bill Clinton

- Colin Powell

- Black politicians like Douglas Wilder and later Barack Obama

Jackson was still respected, but he was no longer the central figure in the national conversation. The media’s appetite for “newness” pushed him to the margins.

8. Internal Movement Fragmentation

The civil rights generation was aging, and the movement’s institutional power was dispersing. Jackson’s base — churches, unions, and urban activists — was no longer unified in the way it had been in the 1970s and 1980s. Without a consolidated movement behind him, his leverage weakened.

9. Corporate and Political Resistance Intensified

Jackson’s economic activism — boycotts, corporate negotiations, anti‑apartheid pressure — had made him powerful in the 1980s. But after 1988:

- Corporations became less responsive

- Political donors shifted to centrist candidates

- lobbying groups worked to limit his influence

His ability to force concessions declined as the political economy changed.

10. The Rainbow Coalition Lost Momentum

The Rainbow Coalition remained active, but it no longer had the national energy of the 1984–88 period. Without another presidential run, the coalition lacked a unifying project. It became more of an advocacy organization than a national political force.

11. Scandals and Personal Controversies Weakened His Standing

- In early 2001, Jackson acknowledged that he had fathered a child outside his marriage.

- The relationship itself was not illegal, but the secrecy — and the fact that the woman had been on the payroll of one of his organizations — created a perception of hypocrisy.

- Jackson temporarily stepped away from public life, and the Rainbow/PUSH Coalition faced intense scrutiny.

This episode sharply reduced his moral leverage in political and corporate negotiations.

12. Financial Scrutiny of Rainbow/PUSH

Throughout the late 1990s and early 2000s, Jackson’s organizations faced questions about:

- payroll practices

- travel expenses

- the blurred line between political activism and personal influence

None of this resulted in criminal charges, but the optics fed a narrative that Jackson’s operation had become less transparent and more personality‑driven.

13. Public Feuds and Off‑the‑Cuff Remarks

Jackson’s influence was also weakened by several high‑profile verbal controversies, including:

- remarks about Jewish political leaders

- comments about Barack Obama during the 2008 campaign

- televised statements that were widely criticized as inappropriate or divisive

These incidents didn’t destroy his legacy, but they chipped away at his stature as a unifying national figure. Jackson’s style — moral appeals, mass rallies, coalition building — no longer aligned with the party’s dominant strategy.

Now that he’s gone, leaving the earthly plane at age 84 after a long illness, Jackson will be allowed the recognition not fully granted while alive. His critics will cease trying to drag him, and he’ll be recognized for his accomplishments. Jesse could be polarizing, but he was attacked as much for the agenda of others as for his own, though he certainly had them. For those with negative opinions of Jesse, take a minute to examine where they came from. Jesse had haters on all sides of the spectrum, some of them upset that they couldn’t be Jesse.