I was often called “white” throughout my childhood, and while such accusations have become rarer, they still occasionally surface. Most recently, I was told, “You don’t watch Black movies,” which seemed to redirect the focus. I responded by naming various Black films and shows I've seen, but the accuser was not familiar with most of them. What she really meant was, “You don’t watch Tyler Perry movies.”

These accusations are ironic, especially considering I typically know more about Black history, culture, and art than many might assume. It seems that having only watched a handful of Tyler Perry films would warrant losing my so-called "Black card"—a symbolic representation of one’s authenticity within Black culture (and no, we don’t actually get a card).

Blackness is sometimes defined so narrowly that it becomes impossible for anyone to check all the boxes. This thought crosses my mind whenever I watch The Blackening for the first time.

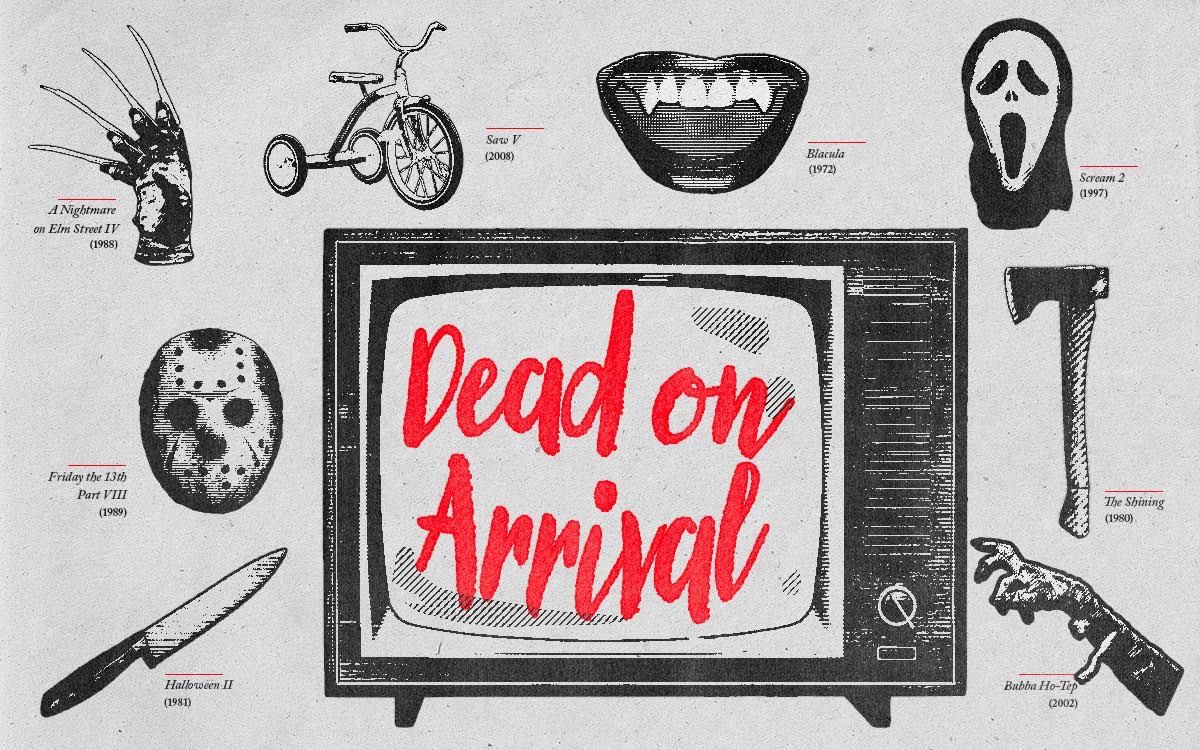

The Blackening is a 2022 horror-comedy directed by Tim Story and written by Tracy Oliver and DeWayne Perkins. If you know me and my tastes, you may wonder why it took me so long to see a Black horror movie crafted by Black filmmakers. I was excited about the film, but I initially perceived it as a parody, akin to Scary Movie—the kind of film I needed to be in the mood to watch. I expected a sillier version of Evil Dead featuring Black characters. While there is silliness, The Blackening also serves as an intriguing satire, rich with the insights of its Black creators.

The film follows a group of friends who visit a cabin in the woods to celebrate Juneteenth, where they discover a game called The Blackening. Central to this game is a caricature of a Black figure reminiscent of Little Black Sambo and minstrel shows. It reveals the kind of racism the characters will face, forcing them to play the game with their lives on the line.

The film's satire becomes increasingly apparent when the group must sacrifice one of their own based on who is deemed “the Blackest.” This ensemble cast showcases characters who possess traits that some might argue disqualify them from being considered authentically Black, yet many are comfortable policing Blackness.

One character, King, is accused of being the Blackest because “you’re the one with the gun and you’re gangsta.” This stereotype of Black masculinity is challenged when King defends himself, stating he has turned his life around, adding that he is married to a white woman—a fact that his friends suggest actually works against him.

The history between Black men and white women is complex. While the film reveals that dating a white woman can strip someone of their Blackness, it also plays into an old stereotype. In The Birth of a Nation, the plot revolves around a Black man (a white actor in blackface) pursuing a white woman, leading to a Klan rescue—perpetuating fears about Black men’s obsession with white women.

On the flip side, The Blackening illustrates how successful Black men often seek white partners, suggesting that some individuals in minority groups view such relationships as a measure of success. However, statistics don’t always support this narrative. According to the Pew Research Center, only about 7% of interracial marriages involve a Black man and a white woman, compared to just 3% of Black women and white men. Even so, the data shows that interracial marriages do not guarantee success, with the largest increases occurring among individuals with a high school diploma or less.

Whether a Black man loses his “Black card” for dating a white woman hinges on how he acts while doing so. Sadly, some men see this as an opportunity to demean Black women, driven by their own self-hatred and internalized anti-Blackness.

The character Dewayne argues he can’t be the Blackest because “I’m gay. Just like my homophobic family members say, gayness is just whiteness wrapped up in a bunch of dicks—and today, I agree.” Though the swagger of gay men often exudes Black culture, Dewayne’s perspective emphasizes that gayness is often viewed as other, and if it isn’t seen as Black, it must be perceived as white.

Many of my students, even in 2025, display troubling levels of homophobia. Most will talk to gay students and even call them friends, yet they still resort to insults like “fruity” or “gay” when it suits them. This rhetoric seems to have increased this year, possibly due to classroom dynamics, with Black football players especially guilty of this language.

Despite some improvements, homophobia persists in the Black community, as evidenced by one of our Black guidance counselors—someone meant to help children—sending his son to a conversion camp. It’s easy to see why Dewayne was quick to say, “Uh uh, don’t try to claim me now.”

When Clifton defends himself, he states, “I voted for Trump… twice.” Needless to say, Clifton was sacrificed—not because he was the Blackest, but for the opposite reason. We can all agree that isn’t Black, right? Except—are Snoop Dogg, Soulja Boy, and Nicki Minaj really shucking and jiving for Trump? They’re just celebrities, but didn’t Trump double his Black support in 2024? Surprisingly, I’ve seen more Black students passionately supporting him now. Unfortunately, it’s true that some Black people, particularly those with wealth, have a fondness for Trump.

Still, these numbers are small in the grand scheme. Even with doubling his support, Trump only secured about 15% of the Black vote. I try not to police Blackness, but I must admit I have my biases. Many of my students' support for Trump stems from ignorance; they often see it as edgy. They understand it can provoke a reaction, especially from girls. I imagine most will grow out of it as they gain more awareness of the world.

The climax of The Blackening brings everything together when it’s revealed that Clifton isn’t dead and is actually the evil mastermind. Clifton is awkward and nerdy, having been teased for not being "Black enough." Although he’s skilled at games, Clifton doesn’t know how to play spades—a serious misstep in the Black community—which leads to his Black card being revoked in college.

After becoming upset, he drank for the first time and ended up driving under the influence. He killed a pedestrian and spent four years in prison planning his revenge. Although Clifton is not meant to be a sympathetic character, his plight still resonates, especially with young people. Like Clifton, I grew up as a Black nerd. It can be a lonely experience, particularly in the 90s when everything I did was labeled as “white”: reading, writing, good grades… even the way I walked.

It’s unfortunate that intelligence and Blackness are often viewed as mutually exclusive. I distinctly remember being called “white” because of my vocabulary. Even now, I’ve taught students who deliberately hide their good grades or fail on purpose to maintain their "Black card." One student went from nearly perfect scores on every assignment to failing. When I spoke to him in the hallway, he admitted he was intentionally failing because of the bullying he faced. Frustrated, I realized I partially contributed to the problem by announcing the highest grades in class. I promised him I wouldn’t do that anymore if he’d commit to making an effort. Fortunately, he trusted me enough to return to his good grades, and I stopped announcing the top scores.

Black nerds and outcasts often respond to ostracization in different ways. I grew out of any loneliness and resentment I initially felt, but some people cling to that hate, using it to justify anti-Blackness and a yearning for approval from whiteness.

I once taught a Black student who openly expressed his dislike for Black people. For a poetry project, he wrote a piece titled “I Hate Black People.” He referred to Black kids as “ghetto,” revealing experiences of bullying. He was awkward and nerdy, wearing glasses similar to Clifton’s. Secretly bisexual yet fiercely Christian, he felt like an outsider even within his family.

Playing the dozens—a verbal sparring game—remains prevalent in Black culture. While it can be playful among peers, it quickly turns into bullying if one doesn’t want to play along. It also makes those who show vulnerability easy targets.

I was never a fan of playing the dozens, but I was particularly good at it. My student, however, struggled, amplifying his loneliness. When he began claiming support for Trump, he became a celebrity among white people, trotted out for appearances. He even visited the White House and was featured in various articles.

They called him derogatory names, claiming it was just a joke. Yet, when a Black kid makes a "Yo momma" joke, it’s unacceptable, but being called a slur by someone with a Southern drawl somehow is tolerated. I can’t blame my student; he was young and looking for acceptance. After graduating, he returned to tell me how much he had changed.

Many Black nerds share similar experiences. I remember feeling like one of those “Black girls don't want me” guys. I could have easily fallen down the wrong path. Fortunately, my grounding in Black culture and art helped me navigate those challenges. We all have our quirks, and that’s the message of The Blackening.

It feels a bit hollow to end by saying, “Don’t police Blackness.” We already know this, but it’s worth acknowledging the subconscious biases at play. Black culture is real, but we all navigate that culture differently. Some people will watch every Tyler Perry movie, no matter how rushed, while others might catch one every few years.

It’s all about Black love, but it needs to be acknowledged that all skin folk aren’t kin folk. As I suggested earlier, Clifton’s biggest issue—if true—was his support for Trump. Figures like Candace Owens use their Blackness solely for personal gain, and their morals run as deep as their wallets. I’m not advocating for blind approval; we need to maintain a discerning perspective.

Was Clifton too far gone by the time The Blackening began? Removing the murder aspect, I can't comfortably say yes. He genuinely wanted to be around people who looked like him; although he didn’t know how to play spades, he was still rooted in Black culture. In fact, the film suggests that Clifton didn’t actually vote for Trump. He simply wanted to escape the game so he could enact his plans without interference. He also understood that voting for Trump multiple times would be unforgivable among his peers. For better or worse, Clifton was still reaching out to his community, wanting his Black card back.

The Blackening may not be the perfect movie, but its premise is something you rarely see in horror media. Initially, I questioned the entire idea because a group of Black people going to a cabin in the woods seemed improbable. Who does that? But that’s the very point the film strives to make—these characters defy the narrow confines of what it means to be Black.

This post originally appeared on Medium and is edited and republished with author's permission. Read more of LG Ware's work on Medium.