Many people around the world love Japanese anime. Dragon Ball is broadcast in 80 countries and One Piece is available on Netflix in 93 countries.

I was particularly moved by the story of Yusuke Urameshi from Yuyu Hakusho when I was a child. I could relate to Yusuke’s hard exterior and his internal desire to help others. He didn’t look like me, but he walked a path I was struggling with at the time. Yuyu Hakusho was a story from the other side of the world, but it was a very human story.

Decades later, my Black students are just as enthralled by anime and manga. I’ve watched kids who will otherwise refuse to open a book consume volumes of manga.

Despite the love Black people have for anime, there are few Black characters. And the melanin-laced characters that do exist feature offensive stereotypes. The influence on these portrayals can easily be traced to the following:

Black minstrels

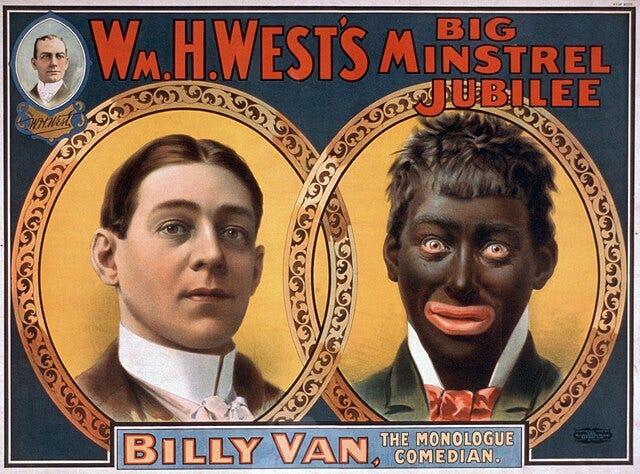

To understand why Black representation in anime and manga can be offensive, one needs to understand the history of minstrel shows.

Minstrel shows started in the 1830s and were ingrained in American culture by the 1850s. They usually present Black characters using negative stereotypes: dumb, lazy, etc. They reduce Black people to little more than animals. The shows are most notorious for having white people portray Black characters using Black face.

Actors would use burned cork and later greasepaint or shoe polish to emulate Black skin. They would exaggerate the lips by making them big and red, creating a clownish look.

The stereotypes established in those shows still impact how Black people are viewed today. Japan had limited experience with real Black people, but they observed what was presented in America, and this shaped their art.

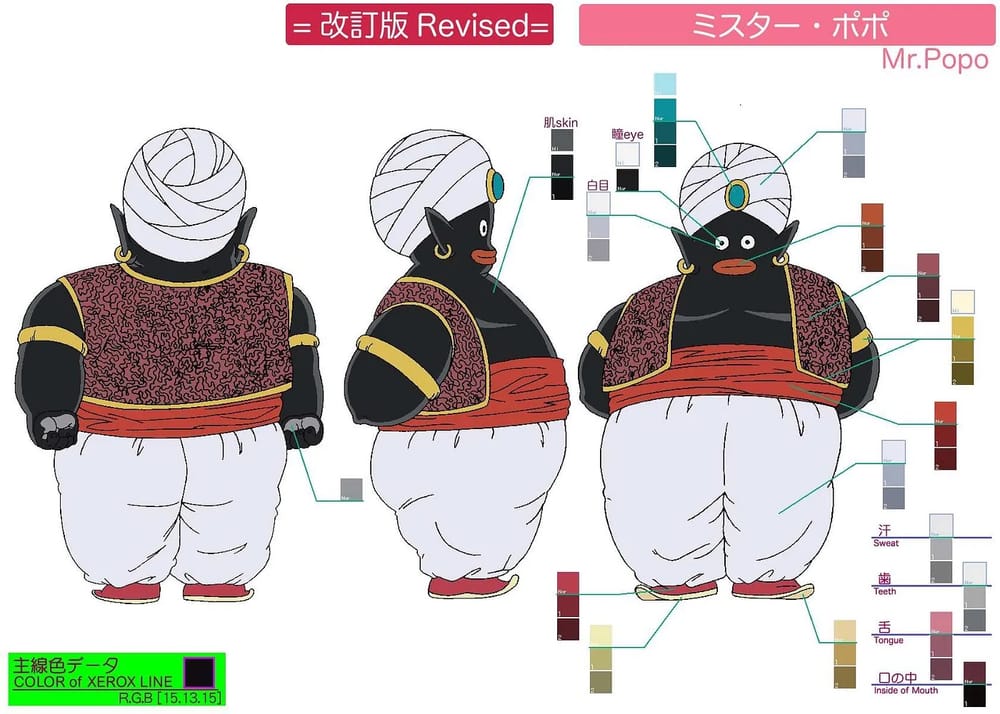

For Black kids my age, Dragon Ball was peak anime. Unfortunately, all of their Black characters (there weren’t many) took inspiration from minstrels. Mr. Popo is the most offensive example.

He is most generously described as the servant to Earth’s guardian. He has black skin, wide eyes, and thick red lips. These lips, I’ve heard them called donut lips, can be found on many Black anime characters.

Even Pokémon, a franchise about little monsters, made room for racist caricatures. Jynx was probably the most humanoid pocket monster. It had long hair and wore a dress, but for some reason, they chose to give it Black skin and the Mr. Popo donut lips.

I remember being called Jynx as a child. It was a good insult, targeting my masculinity and dark skin simultaneously. I understood that Pokémon were diverse creatures in all shapes and sizes, but Jynx always stood out to me. Why was it so different? What motivated someone to create an “animal” that looks like that?

Professor Amy Shirong Lu says: “From the very beginning, Pokemon was intended in part for export, and the production team aimed for a universal feel acceptable to international audiences.”

Reading this, I ask myself what would draw American audiences to Pokémon? Is it the whimsical nature of the creatures? Is it the dragons and the opportunity to trade with friends? Naw, Americans really love racism. We need to throw some of that in there. I can only assume this was the thought process in creating Jynx, and honestly, they weren’t wrong.

Sister Krone from Promised Neverland is a more modern example of a Black character falling into minstrel tropes. It is less obvious than Mr. Popo and Jynx. Her skin isn’t unrealistically black, and her lips are still big but more believable. However, unlike Mr. Popo and Jynx, Sister Krone falls victim to other harmful stereotypes.

She is the mammy archetype, modeled after a character like Aunt Jemima. Mammies come from the minstrel world and depict Black women as domesticated caregivers who are happy with their enslavement. Aunt Jemima is the most famous example of this stereotype.

Michael Twitty, a historian and author, said: “Aunt Jemima, Uncle Ben and 'Rastus,' the Cream of Wheat man, were actually meant to be stand-ins for what white people viewed as a generation of formerly enslaved Black cooks now lost to them. As mascots, they were designed to be perceived by those white people as nothing more — and to have wanted to be nothing more — than loyal servants, in a frightening time of growing Black equality and empowerment”

Promised Neverland is explicitly a show about an oppressive society, so bringing in a Black character, people known for being oppressed, feels purposeful, especially when she is presented in contrast to Sister Isabella.

Isabella presents as white or traditionally Japanese. She is soft, nurturing, cunning, and feminine. Isabella is a threat to the children in the story because of her intelligence.

Krone is strong, fast, and animalistic. Black women have always had their femininity stripped from them. Even now, Black women are constantly accused of being “not feminine enough”. Sister Krone seems to represent all of this. She is a threat to the children because of her Blackness. The idea of Black people being closer to animals is an old one. Even when Krone chases the children, she moves more like an animal than a human.

Admittedly, Krone is a complex character, but like many Black characters built around stereotypes, she is dismissed and killed while the more important non-Black characters regain all the focus.

So, a few manga artists made some slightly racist pictures. They probably didn’t understand the social context. What’s the problem?

To be clear, I’m not offended by these characters. In fact, I’m a fan of sister Krone. The problem, however, is how these stereotypes are often the only representation people get.

When I was in college, I met a guy from Poland. He said he didn’t meet a Black person in real life until he came to America. Like Japan, Poland has a very small Black population. He thought all Black people were like the ones he had seen on television. He even believed we got lighter when we bathed.

When all the media dehumanizes us or makes us out to be monsters, it reinforces the oppressive systems already in place. It makes people who have never met a Black person hate Black people.

This doesn’t even touch on how Black people view themselves. As a child, it was hard for me to find Black characters in the nerdy media I enjoyed. When I did find them, they were stereotypes usually shunted off to the side or existed to make the protagonist look better. Looking back, I internalized a lot of that hate, and I was in college before I was able to reprogram myself. I know people older than me who are still struggling with that programming.

No, this isn’t about being offended, but realizing real harm can come from these negative minstrel portrayals, especially when they are far more common than realistic and diverse depictions of Black people.

The community

When researching for this piece, I was reminded just how hateful anime fans can be.

Although anime is basically ubiquitous, some fans really hate it when Black people and women join in on the fun.

This can be easily seen in the comment section of any video of a Black woman cosplaying an anime character. They feel compelled to, at the very least, point out that “x” character isn’t Black.

A few years ago, Shirleen, a Black cosplayer, posted an image of her cosplaying Rin Tohsaka from Fate/Staynight. She took screenshots of all the hateful and racist comments she received. Sadly, this is the norm, and when Shirleen shared her story, other Black women came out about their experiences. One person commented, “They hate us just for existing.”

I have to ask myself why anime draws in so many people like this. Does anime reflect this mindset? It is a diverse art form, and no doubt some of it glorifies homogeneity or racism.

Japan is an amazing place. However, the reason I value Japan and the reason these fans place Japan on a pedestal is slightly different. It goes back to that word homogeneity. Their fantasy of Japan is an ethically cleansed place with traditional gender roles.

When they see a black person in their fantasy, it angers them. It isn’t too different from how people get upset in the West and complain about movies being “too woke”.

I have to point out that Japanese people online can also be angered by Black people enjoying anime. A sixteen-year-old posted artwork she created of two characters from Dandadan. She remade the characters as Black Americans. I only saw a child who was inspired by something she loved and created a piece of art.

Unfortunately, some Japanese fans were not happy. One person said, “I’m Japanese. Stop making Asian characters Black. We’re not Disney characters.” This comment received 342,000 likes. The image even made it into Japanese forums like Yaraon. I can understand feeling protective of your culture’s art, and it shows how complicated these relationships can be even in the most casual situations.

The sixteen-year-old privated her account and was likely spurred away from the anime community and artistic endeavors at least temporarily.

Luckily, despite the animosity, there are plenty of welcoming anime fans, especially in the real world.

To be fair to Japan, they are not the only ones to depict other cultures in a negative and stereotypical light. America portrayed Japanese people and the Asian community as horrible stereotypes for decades. Even once they got past the more apparent racism, like yellow skin and a demonic look, America still sometimes presents Asian characters using dehumanizing stereotypes.

America is more diverse than Japan, and we still fail to get it right. Japan is over 98 percent Japanese. The number of Black people in Japan is a fraction of half a percentage point.

It is no surprise that a single manga artist struggles to depict Black people when they have so little firsthand experience, and when their only mainstream exposure comes from racist, American propaganda, the results are actually not that surprising.

Nevertheless, manga and anime are getting better at representing Black characters. This effort goes back to 1988 and The Association to Stop Racism Against Black People.

The association sent letters to creators and companies for problematic or a lack of Black representation. It was the association's work that made the more racist depictions taboo in Japan. It was necessary for a Japanese group to do this to spark real progress.

Characters like Mr. Popo and Jynx were changed to be blue and purple, respectively. Black characters in anime overall have become more realistic and well-rounded.

I am currently watching one called Lazarus. My favorite character is Doug Hadine, a Black man who doesn’t fall into any of the stereotypes. His skin and hair are realistic. He is an intelligent physics major with an eye for detail. He is calm and measured and tends to plan and lead the group. He is just a well-developed character who receives as much care as any of his teammates.

Saturday AM, an English-written international shonen manga anthology magazine, is currently publishing Clock Striker. The series is marketed as having the FIRST Black female Shonen hero. Although it did not originate in Japan, Clock Striker is gaining popularity globally, including Japan. Stories like this are refreshing to see, and I expect many manga creators to be inspired when they create Black characters in the future.

I love anime. I love Japanese culture. I appreciate the styles and stories they share with the West. Anime helped shape who I am today, including my eye for injustice.

Japan is not the only culture to use harmful stereotypes in its art and media. Americans are especially notorious for this.

Calling out these problems isn’t about being offended or having some political agenda. It is about thinking about the humans behind these identities, and what we can do as a people to get better.

Anime, despite its problems, is an amazing and diverse art form. I’m excited to see it grow and continue to get better.

Special thanks to Yuri Minimide for advice and contribution

This post originally appeared on Medium and is edited and republished with author's permission. Read more of LG Ware's work on Medium.