I’ve never used the phrase “This is America” to mean something good. That’s reserved for moments crushed underneath this country’s specific threat. On a Wednesday night at the Barclay’s Center, Caitlin Clark's Crew showed up in full force, packed the house with interminable pride and power and spit and piss and vinegar. Scanning the crowd, I only saw white folks wearing Indiana gear. Twelve-year-old girls are the electoral majority of Clark’s clan, but at the concession counter, there was a mid-50s couple: wife’s reddened hair in a straw-straight blowout, hubby with the “1776” shirt, Blue Lives Matter Flag on the sleeve.

Just what in the January 6th has Clark brought out in American basketball fans? But oh.

This is America.

When I explained the racist signifying to my friend and how to read it, she asked whether I thought Clark had some part in its genesis.

Yes and no.

Caitlin Clark is great at basketball, I said, with no qualifiers yet. But then, pro hoops brings its inescapable cultural baggage into otherwise benign conversations. In a racist country, distracted by our immediate trappings, nothing good comes without its own bigoted boil. The permanent scars of history, and its recent bruises (Angel Reese and Caitlin Clark’s feud, commentators picking sides, the unfortunate truth of Clark’s worst basketball year) render the story as harmful as Bird versus Magic was powerful.

“Well, there’s not as many good white players so I’m sure that has a lot to do with it,” she offered.

“I would say that but this game has Breanna Stewart, a former MVP, in it, and her teammate, Ionescu, is a good white player too. Caitlin Clark is two things American white culture latches onto: straight and angry.”

Then I unpacked the history of smooth white female ballers, some lesbian, some masc, and why the zeitgeist had rejected them. Diana Taurasi’s too gay and from a bygone era. Sue Bird, queer icon, celebrates a marriage to another famous lesbian, the kind white men never like because she’s outspoken and uninterested in their feedback. And there sure ain’t been no Black women upon whom they could project their grievances and also see themselves in. Unless you got Oprah to suit up, try that behind-the-back spin move, and somehow thank her opponent for letting her play. Clark set the WNBA on fire with her distance shooting. But the open secret is the burning cross it’s left smoldering in her fanbase.

I’ve developed an irrational, well-reasoned hatred of Clark on the court. The Fever fan video edits from her limited on-court time this season are brutal. She slouches and shrugs when others miss; she screams at refs in call-the-manager arpeggio. She looks like an insufferable teammate and co-worker. But her cohort can’t really say shit to her because her swag, her seldom-made 30-footers, and straightness bring in major coin. That’s not to mention her constant flopping, phantom defense, and winless past.

When I outline her basketball ethics, Clark is a malcontent. She’ll probably be one of the first 60- or 70-point scorers in a game in her league. I imagine a stilted sixty though, full of running up to shoot her shot behind a gaggle of blockers and screens. Her teammates will cheer for the unending camera gaze as they log more game minutes than points. Her sneakers will light up in a conflagration of brand deals and sponsor call-outs. The marketing managers will be hard at work making AI porridge copy.

“We shoot for the stars because the moon got tired of us” or whatever.

And while women’s empowerment often hinges on the rights of the already untouchable white feminine, the benchwarmers cheering her on will suffer the animosity of newbie fans who tell them they don’t deserve these spoils. It makes you wonder which women they’d like to be rewarded? Who gets to enjoy the overdue pay bump?

For WNBA All-Star Weekend, the StudBudz, a Black lesbian podcast duo of Courtney Williams and Natisha Heideman, turned this justice conundrum upside down. They frequently joked that they would have to “Call Caitlin” if denied any access for their 72-hour All-Star livestream. The joke is in the telling. On a livestream, Clark’s people, the WNBA, the millions of trolls, could not stop the momentum of an inside joke: we go as far as white hype goes and no further.

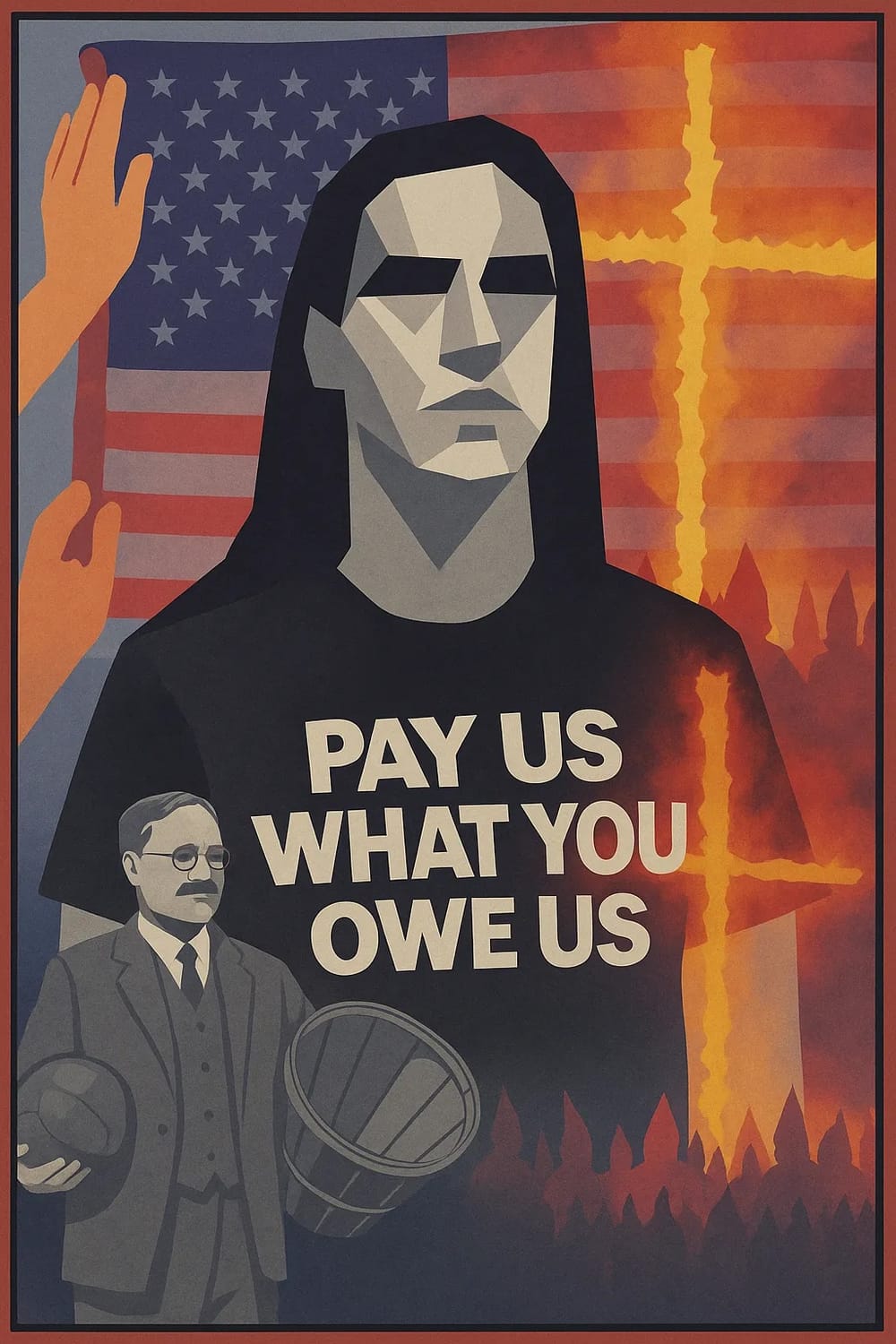

Clark’s off-court politics angle for solidarity. She has been vocal about lifting up all women in the league with this new attention, and has urged fans to be inclusive and warm to her colleagues. She showed up to All-Star Sunday in the well-coordinated labor rebellion t-shirt that read “Pay us what you owe us.” Who knows how much this message reaches the MAGA cornhusker rank-and-file in her comments. She didn’t sign up to be the poster princess of white backlash, but this is America. That’s the plate she eats from, Nike endorsement aside.

Yes, Clark has to carry it. But not for me. My racial injustices predate her birth so I’m sorting through them one by one.

There’s more emotional gratification for me as an angry casual, snuffling for scraps of hate, than as an informed diehard. I will hate Caitlin Clark in honor of all the white women who wronged me and have yet to wrong me. That’s the problem, my White Woman Problem.

I am a personal historian of White Girl Fever so I tried to trace the inane imbalance in me, the hair trigger distrust of the white femme.

Was it Ms. Polsky, the fifth grade teacher who wanted more from me than it seemed I could give? She sent me off to sullen corners when I acted out in class and overturned reading hour with stutter giggles and paper planes. I could’ve been more like the Black girls around me, quiet at all costs, clocking every angry tic, from Polsky’s jumpy shoulders to her downturned lips with crossed arms. She was a Caitlin Clark brunette who clashed with my mother over bad grades and frequent disciplinary spats. And mother, the Black woman fighting for every inch and pound of son she couldn’t be or feel, would let me know that Polsky’s martial obsessions came from Whiteness, not care. Came from her need to dominate the classroom instead of guide it.

Or was it Shannon Bishop, the nonprofit boss whose web history leaked visits to the Stormfront site years before white nationalism was en vogue again? Shannon’s green pupils widened when she approached my desk, hovering with a list of tasks. She was sure to watch me type and had me repeat back each one before she skittered back to her desk, also near mine. I spent weeks sick to my stomach, stressed I couldn’t please Shannon who was planning her debutante wedding. Was the devil in her details, aqua nails manicured to polite nubs? A Pilates-cinched core, revealing a shivering, unwavering, sad, disgusting, wanton commitment to size-zero living. I had, that summer of 2010, just begun throwing up buffet salads to get a 32 waist in my Dockers. Within a month, I got there but had been calling out so much from work that I now reported to my boss’s boss in daily minute-keeping that was the evil twin to my calorie tracking. I had to be watched, they knew, lest I continue my 27-year streak of living despicably Black. A night creature, a shadow merchant, I had violated the workplace covenant to never be seen.

Near broken, I asked my co-worker Lisa, Shannon’s other direct report, to join me for Asahis and a vent. We shit-talked Shannon’s erect coat hanger shoulders, bleached teeth, clicking tongue, and incessant typos. (For a Publications Manager at an amnesty organization, she could not fucking spell.) Then Lisa simmered, turned her nose down to her chin and said, “I think Shannon is a racist.”

We hadn’t discussed race. I’d assumed Lisa was white, but she had an Asian parent. That ambiguity had opened the door for Shannon’s Aryan nation slips. A comment about the number of Asian students at Ivy League schools sizzled into the air and away. A question about why we funded so many Iraqi scholars ‘at a time like this…’ tripped me up. I filed it in my deepening wrinkles.

And because I didn’t esteem bigotry could be ‘micro,’ could flow in and out of standard chat, I left it alone. Though I eventually got fired anyway for missed days and delinquency, I had lined Shannon up in my head. The game of my life was “Beat the Racists” and every level had a boss with astoundingly subtle super powers. Shannon’s was camouflage, Polsky’s was militance, and Caitlin Clark’s is media training.

Caitlin Clark is a right-side-of-history quote machine. Her intentional allusions to radical Black thought strike me as phony. But she’s just doing the job. In press conferences, she executes. She pays her flat justice tax in each solidarity statement. The following quote was Clark’s sparkly introduction to NBA race/gender politics. It is perfect.

“I want to say I’ve earned every single thing, but as a white person, there is privilege. A lot of those players in the league that have been really good have been Black players. This league has kind of been built on them. The more we can appreciate that, highlight that, talk about that, and then continue to have brands and companies invest in those players that have made this league incredible, I think it’s very important. I have to continue to try to change that. The more we can elevate Black women, that’s going to be a beautiful thing.”

I wanted to throw up in my mouth when I saw the clip. Had she been coached? Where was the dog whistle? The wink and nod to the White audience foaming for her to drop a reference to uplifting their players too? Clark wouldn’t play that game, and doesn’t believe in it.

I, for one, find it gross. I need to litigate all of my White woman grievances through her mistakes, lean my anger on her jump shot, and distort her persona to fit my old wounds. She’s supposed to say she earned everything she got, not claim privilege. The toxic online sludge says she should, and so does the algorithm. When she broke from the pattern, I couldn’t process. Taylor Swift did a country album, at least. Clark should embroider a blue flag in her merch like her Stans do.

Or else what is it all for? I want my hatred to eat away at me, leave a husk of crumbling childhoods, latent fears. I want revenge for the $300 seats that sat me so far up in the nosebleeds, I felt like I wasn’t watching a game at all. It was a concert, a festival of jeers for the Black league and blind faith in its white savior. I want to shoot righteous anger at Linda Polsky and Shannon Bishop for the rest of my God-given days and curse their names until I’m out of breath or my pen is out of ink or both. I want to stand up to every suspicious boss, every purse-clutcher, every white girl who touched my hair and caressed my face, rode me into reluctant bliss as I tried to deny my orgasm before I came. I want to be braver in the past than I’ve ever been at anything, and much stricter about revenge.

I want to rewrite the WNBA so a Black woman saves it. I want every dollar Caitlin Clark earns to pile up in a mountain of misery as her family fights for who will sell the first autographed sneaker. I want to live out a symbiotic pain, spiraling into a collective downfall. Like a proper country.

But this is America.

This post originally appeared on Substack and is edited and republished with author's permission. Read more of Andrew Ricketts' work on Substack.