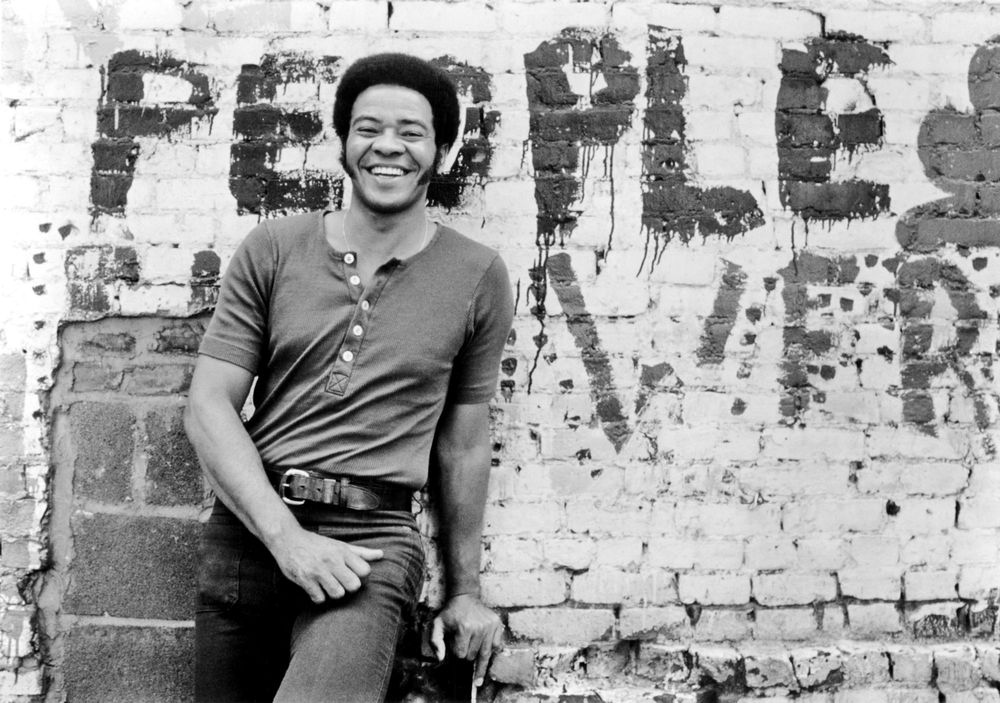

“You gonna tell me the history of the blues? I am the goddamn blues. Look at me. Shit. I’m from West Virginia, I’m the first man in my family not to work in the coal mines, my mother scrubbed floors on her knees for a living, and you’re going to tell me about the goddam blues because you read some book written by John Hammond? Kiss my ass.” —Bill Withers, 2005

Bill Withers is one of those artists I keep in my pocket for people who tell me they don’t listen to certain types of music. If they claim they don’t like blues, I say, “Oh, you don’t like ‘Ain’t No Sunshine?’” If they say they don’t listen to much gospel music, I hit them with “What, you don’t like ‘Lean On Me?’” Without fail, they end up stuttering amendments and qualifiers. The reason why this trick works is because Bill Withers is like air: You don’t think about how present it is in your life. You just breathe.

It only took Withers two albums to secure his place in music history, 1971’s Just As I Am and 1972’s Still Bill. In those 22 songs were 90% of the biggest hits of his career: “Ain’t No Sunshine,” “Grandma’s Hands,” “Lean On Me,” “Use Me.” As debuts go, Just As I Am is a bit of everything, but in the best way: a mess of blues and gospel mixed with a heaping slap of soul, and a pinch of folk for texture.

It’s easy to look back now and see greatness, but think about what Withers was competing with in 1971. Aretha Franklin at the height of her powers, the Temptations, the Jackson 5, the summer of Jean King. Even Marvin Gaye’s What’s Going On came out in the same month. Withers still managed to explode onto the scene — not by being louder or dancing better or being more proficient on his instrument. He simply wrote songs that could not be denied.

In the first four years of his career, Bill Withers had no B-sides.

Consider what is arguably his most famous anthem, “Ain’t No Sunshine.” When we hear the placeholder chant where a third verse was originally supposed to go — the famous “I know, I know, I know” refrain — anyone who’s ever had a broken heart knows what Withers knows. I knew it when I had my heart broken by a girl in kindergarten and when I broke several hearts in college. I knew almost from birth what a sunless day meant, how long “gone too long” was down to the second, how a home can turn into a house even when the numbers on the curb stay the same. It is a blues composed the way all the best blues songs are composed: without concern for how a song is supposed to be done. The song has no proper chorus. Other Withers songs have more verses than a popular song is supposed to have. Many of his songs straddle multiple styles at once, but all are sung with his signature earnestness, the main ingredient in any original Bill Withers song. It is why covers of his songs are fine, but his post-industry career spent licensing original recordings was equally lucrative and three times longer than the time he spent under label contracts.

Anthony Bourdain once said that if his career as a celebrity writer and TV personality ever blew up in his face, that there was “always a brunch gig.” Failure held no fear for him because hard work was a known quantity, enabling him to live as he pleased. It was his chief appeal; it was also an ethic that Withers subscribed to. By the time Withers signed with Clarence Avant’s Sussex Records in 1970, he was 32 years old and had already traveled the world — already known grown women, already done backbreaking work, already familiar with the bouquet of poverty. By comparison, music was an easy gig, and becoming a national sensation his first time at bat only steeled his resolve to remain captain of his fate. He wanted to do the music he wanted to do with the players he wanted to play with. He wanted an honest day’s pay for an honest song’s merits. And while he battled for years at Columbia when Sussex folded (he didn’t release an album between 1977 and 1985), by the time he left the business in 1985 he had created a catalog that would assure him and his family comfort for the rest of their lives.

“We do not have to wait to see how his legacy will play out: Withers was already at every cookout, line-stepping between every menthol kiss and sugar grits argument.”

The setup for Bill Withers’ song “Who Is He (and What Is He to You)?” is a familiar one in music: a guy hanging out with his lady realizes she may have more than a passing acquaintance with a man who happens by. The title also serves as a launching pad interrogating a deeper cultural question about his legacy. Who is Bill Withers to you, the listener, and what does it mean?

There are two kinds of legacy: the kind that resides in the existence of a body of work, and the legacy that comes from the effect a body of work has on the world around it. Withers is an example of both, able to measure his success not only in market penetration, but cultural impact: the millions of lives changed by the presence of the right song at the right time, the ideas and decisions inspired by a lyric that hits just so, the swaying of a stadium of people leaning into one another for a moment in time that lasts forever in the soul. Withers’ legacy is less about his songs as music and more about how we apply them as lovers, workers, and neighbors. There hasn’t been a day since 1973 when someone, somewhere didn’t play a Bill Withers song. We do not have to wait to see how his legacy will play out: Withers was already at every cookout, line-stepping between every menthol kiss and sugar grits argument.

No doubt: Creating powerful art is a legacy.

That said, Bill Withers songs are not complex. Musicianship is not why his songs work. Withers’ music is a lot like the man: It has no patience with artifice. The singer could not tell you where most of his ideas came from, save digging deep into one’s self. What is clear is the thread of sensitivity that runs through his work that somehow withstood blaxploitation rising, his tunes serving as a tonic against the toxic masculinity to come in both Black film and, eventually, Black music. While the world was watching Superfly, Withers was doubling down on a post-civil rights Black vulnerability that was evident in funky workouts like “Use Me” and “Kissing My Love,” but is best characterized by the imploring anthem “Lean On Me.”

Walking away from the music industry would be a sad story for almost any artist other than Bill Withers. His independence was rooted in self-awareness. He sought (and fought) to stay true to himself, and when he didn’t, bad things followed: bad marriage, bad record deal. Whenever he stood his ground on what he knew to be true of himself, it was a win. Most celebrities never find that kind of peace, and it is the rarest of them who are willing to step away from an artistic-industrial complex built more on ego insurance than talent. By contrast, Withers knew what the world outside of music was made of. There may have been some regrets, but few reasons to give up his well-earned freedom in order to rectify them.

Audiences do not make it easy for artists to be authentic. Too far in one direction and you’re labeled eccentric and impenetrable, too far the other way and you become plastic. The record industry being what it is, these decisions are rarely left up to the artist, which creates an antagonism that often cripples their art even under the best of circumstances. Withers’ success was ultimately measured not by how many records he sold, but in his ability to walk away from a system designed to make him live an inauthentic life. Withers was a proud and intelligent Black man unafraid of plumbing his vulnerabilities before the world, a man who not only knew what he wanted to do with his music, but was keenly aware of what wouldn’t make him happy as a person. And because record companies bend people like that into commodities seemingly by design, Withers determined it was better to rule in a heaven of his own making — healthy licensing checks, raising a family, being present in his life — than serving in a record industry hell.

People often prostrate themselves when a musical legend dies, bemoaning the loss of a voice or gift. This is not out of line; all people should be mourned by someone. And yet, where is the artistic loss to those who did not know Bill Withers personally? His legacy has been secure for 35 years. There has been no reason to expect any new Withers music for several decades. In that light, his oeuvre is a gift we got to open on Christmas Eve. He gave the world the entirety of his art and walked away a free man. He collected every rose he had earned by hand. At any point that he wanted to come back to music, he could have, and been more successful than he was before.

Withers made music not to be famous, but to live a fuller life. He didn’t want to start record labels or sign acts or tour. He knew what he wanted to do, and he died free doing just that. His music, as great and timeless as it is, is a doorway to those deeper human lessons.

There is a profound beauty, after all, in witnessing someone swing for the bleachers, knock the world off its axis instead, and then walk out of the stadium.