Illustrations: Xia Gordon

January 2017. Morehouse College. I was about two weeks into my first semester as an adjunct professor — nervous, unsure of myself, and overthinking everything — and walking down a corridor in Brawley Hall with a colleague. She yelled out to a student in front of us.

“Hey! Take that durag off in the building. You know better!”

Then she looked at me. “You don’t let your students wear durags in your class, right?”

“Of course not,” I lied.

A few months later, outside of the confines of the dorm rooms and academic buildings, a group of Morehouse students concocted a celebration that would go viral and revitalize the fervor around one of modern Black culture’s most enduring staples. That fall, students gathered on campus for Durag Day, where they sported their flashiest wraps, unveiled their most pristine waves, and posed for selfies in a daylong celebration. The festivities reverberated across social media and swept both HBCU and PWI campuses across the country. Durag Days became a thing.

We never stopped wearing durags, of course, but they were relegated to the dark of night like a secret. They weren’t fashion anymore.

The day showcased ingenuity, creativity, enterprising initiative — all the things you want from a Morehouse man. And all in celebration of something the students aren’t allowed to wear in the academic buildings. Therein lies the heart of the controversy surrounding the famed headwear: a symbol of negativity for some, a beloved cultural touchstone for so many others. But how did we get here? How did a harmless means for hair maintenance become so divisive?

The exact origin of the durag is unknown, though according to a 2018 New York Times story, So Many Waves president Darren Dowdy claims his father invented and began selling durags in 1979. Whatever the case, Black people have been sporting head wraps for centuries as a simple means to keep hair intact, especially while sleeping. However, the durag became a cultural statement in the 1970s as the Black Power movement embraced the notion of natural hair and all the trimmings that came with it. Durags became an iconic partner to the afro and hair picks with the fists at the end or the stocking caps that kept our heads warm and our hair intact.

Anytime Black people find power and identify with something, it becomes a source of controversy. Natural hair, locs, black berets, Africa medallions. The durag was no different.

By the time the 1990s and early 2000s rolled around, the durag was a centerpiece of Black identity. Rappers like Jay-Z, Nelly, and the Dipset crew were sporting durags in music videos and album covers as part of the rap uniform of big-ass white tees, chunky gold chains, and baggy jeans laid over sneakers. “Made ’em relate to your struggle, told ’em ‘bout your hustle / Went on MTV with durags, I made them love you,” Jay rapped on the 1999 track “Come and Get Me,” celebrating his ability to be authentic while making power moves.

Of course, rap gear is often a reflection of what Black people are wearing in neighborhoods across the country. And eventually, kids in those neighborhoods would grow up to be household-name athletes who would also become torchbearers for what was cool in Black culture. The early 2000s saw NBA MVP Allen Iverson and NFL phenom Michael Vick, two Black men from Newport News, Virginia, embrace the rap aesthetic to cover magazines, star in commercials, and become household names. Durags included.

“Those two are so significant in an entire generation’s cultural upbringing,” says Justin Tinsley, a writer at ESPN’s The Undefeated, who hails from Vick and Iverson’s home state. “I won’t say guys like Iverson and Vick started the durag trend, but in Virginia, a lot of us found inspiration in them doing that. You want to be as cool as they felt, however you could.”

That sense of cool, though, was crashing against another turn-of-the-millennium cultural moment: the rise of respectability politics. The 1994 Crime Bill and Michael Bloomberg’s Stop and Frisk policy as mayor of New York City helped further legislate the criminalization of Black people who fit a description. For Black people, those descriptions felt like dog whistles that included durags, especially as racial profiling grew increasingly rampant. The durag became a state-sanctioned symbol of criminality, an easy signifier for those looking to sideline young Black men — like the security guard in 2003 who told me I couldn’t enter a mall in St. Louis because I was wearing a durag.

“There’s a negative connotation in the White community,” says photographer and artist Annie Bercy, whose portrait series Waves highlights men of color in durags in order to dispel negative stereotypes about the garment. “Durags, for them, [symbolize] people who are no good; but it’s just Black people being Black and being punished for it.”

Black leaders responded by admonishing a younger generation for its style of dress. Bill Cosby’s infamous “Pound Cake” speech in 2004 lambasted “people with their hat on backwards, pants down around the crack.” So did professional sports leagues, though they spoke in policy rather than prose, with the NFL banning durags in 2001 and the NBA instituting a dress code that did the same in 2005.

Soon, athletes were wearing (very large) suits and ties to post-game pressers. At the same time, Jay-Z was pushing his “30 is the new 20” businessman chic of button-ups and baseball caps. We never stopped wearing durags, of course, but they weren’t fashion anymore — they were relegated to the dark of night, like a secret.

It seemed like that’s where durags would stay forever. But the convergence of social media, the movement for Black lives, and the erosion of respectability politics changed everything.

In 2012, a Black teenager named Trayvon Martin was murdered as he walked alone at night, shot at close range by a civilian, George Zimmerman. The ensuing court case created a national dialogue about racism, and part of the discussion revolved around what Martin was wearing: a hoodie. It was the hoodie that Zimmerman keyed in on in his 911 calls before he confronted Martin, and it was the hoodie that Geraldo Rivera blamed for Martin’s death. “I am urging the parents of Black and Latino youngsters particularly to not let their children go out wearing hoodies,” Rivera said in an infamous Fox & Friends appearance. “I think the hoodie is as much responsible for Trayvon Martin’s death as George Zimmerman was.”

A chorus of resistance rang out articulating the thing Rivera and his ilk had overlooked: Racists will kill and incarcerate us no matter what we’re wearing. Martin Luther King Jr. had on a suit when he was assassinated.

The tide of the Black Lives Matter movement swept away the respectability politics that had dictated so much of Black discourse in the ’90s and early 2000s. The truth had become painfully, fatally clear: Tucking away durags won’t save us from anything. Only dismantling racism will. “Wearing T‑shirts, jeans, and hoodies to protests became an intentional act of rejecting ‘respectability,’ instead of trying to look wealthy and White,” Bree Newsome wrote in The Atlantic in 2018. The durag put the literal cap on that rejection, becoming part of a celebration of authenticity and unapologetic Blackness.

The durag is a reminder that no matter who we are, what our financial status or living condition, we still take a tiny piece of fabric from our bedside, wrap it on our heads, and go to sleep.

In 2014, Morehouse alum and journalist Vann Newkirk started the Twitter hashtag #DuragHistoryWeek, celebrating iconic moments of Black people rocking the headwear. The moments became part of Twitter lore. “I hope the lesson here is that it’s cool and beautiful to be whatever kind of Black person you want to be,” he told The Fader in 2016. “The little things that we often run away from because they validate stereotypes or make us look like ‘regular’ Black folks are to me things we are now seeing and realizing that we can enjoy without shame or hiding them.”

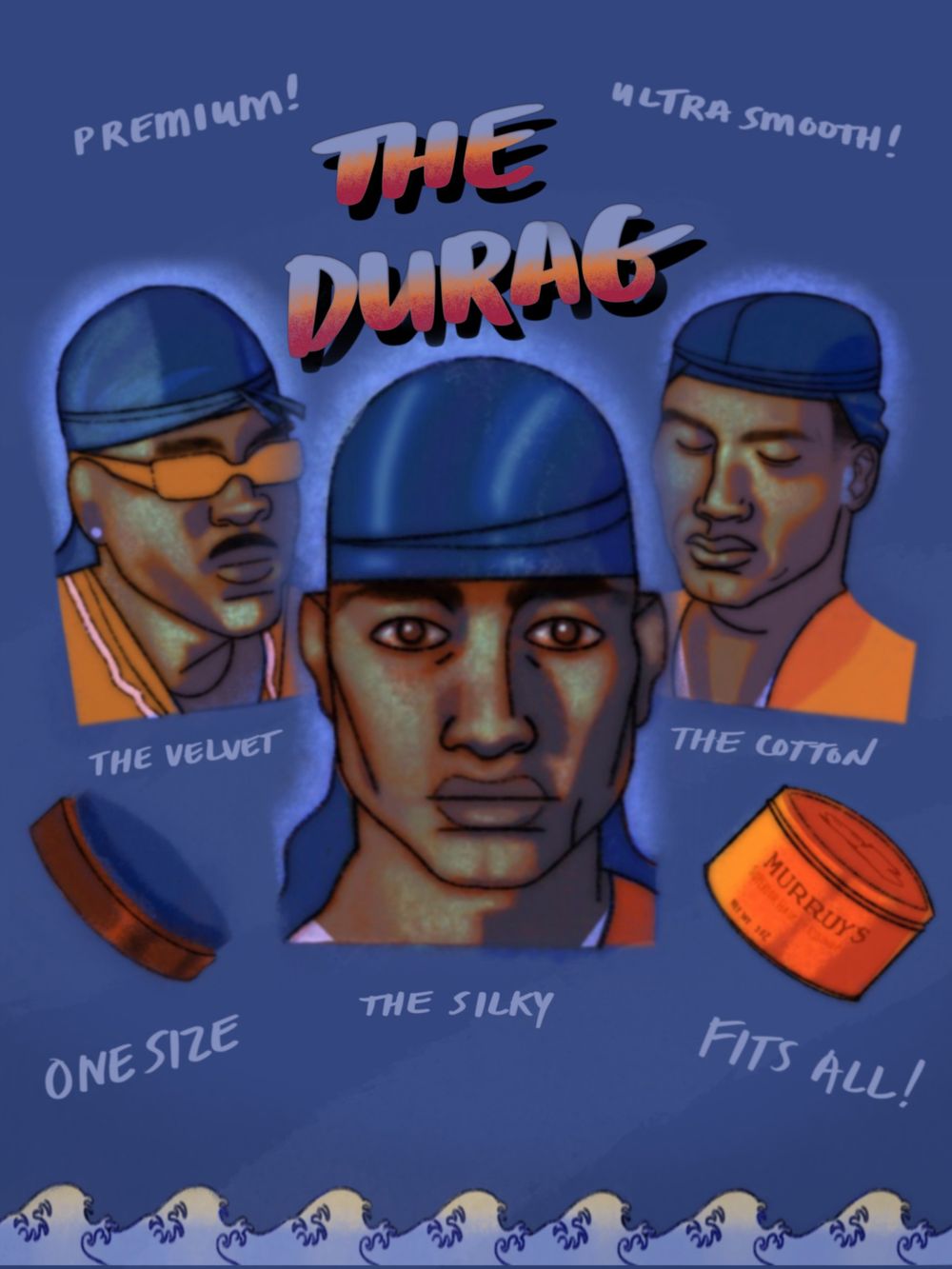

Black creatives started using Vine and YouTube to showcase wave reveals, dramatically removing durags to unveil shiny, pristine, sharp waves. Last year during All-Star Weekend in Charlotte, I ran into two friends who were heading to a Durag Fest, a gala of high-end fits and the most flamboyant durags imaginable. The event became a hit in Charlotte, even touring to Atlanta for a party.

As Black folks across the country and the internet went back to their silk-tailed roots, rappers and celebrities with an affinity for the ’90s embraced the durag anew. A$AP Ferg became rap’s unofficial durag spokesperson, pairing the accessory with gold teeth and a retro aesthetic. Any lingering doubts that the durag resurgence had gone mainstream vaporized when GQ recruited Fergenstein for a how-to-tie-your-durag video.

And when a staple of Black culture becomes a household commodity, you know what comes next: White folks try to claim it as their own. New York Fashion Week in particular became a starting point for the phenomenon, with White designers sending White models down the runway wearing durags, from Rick Owens in 2014 to Tom Ford in 2018. In 2016, Kylie Jenner showed up to the event sporting a fittingly white durag of her own.

Fallout fell out. “Although on the surface, [it] seems like a silly, trendy borrowing of ’90s hip-hop culture, what is actually happening is that the reality star is carrying this look into public spaces where Black people also wearing du-rags might be denied access or harassed for wearing them,” wrote Refinery29. Black Twitter was more direct: “If white ppl [sic] start wearing do rags I’m going to be hella pissed.”

The draggins weren’t confined to Kylie (who, don’t forget, also tried to pass off cornrows as “boxer braids”). Every time White people come around with some interpretation of a durag, it’s rebuffed. Emphatically. When clothing company Nasty Gal promoted a “vegan leather du-rag” for $50 in 2014, it became a trending topic and source of ridicule across the ’net. When comedian Godfrey posted an Instagram video last year of White teens in durags hollering “wave check!” the sob emoji amid the laughter made it clear: Durags were a no-fly zone

If anyone was going to make durags mainstream, it was going to be Black folks, and Black folks only. Rihanna wore a Swarovski crystal-studded durag to the 2014 Council of Fashion Designers of America Awards. Solange wore a durag to the Met Gala in 2019. Beyoncé and Jay-Z had dancers in durags at the Louvre for their “Apeshit” music video. Black-owned Brooklyn-based fashion line L’Enchanteur sold its durags for $130 and ended up on the cover of A$AP Ferg’s 2017 album, Still Standing. The durag is reaching high art, too: John Edmonds’ photography series on durags appeared in the New Yorker.

All the while, in spaces that were more traditionally theirs, Black folks kept flexing, pushing the durag beyond a mere accessory. In January, Oakland rapper Guapdad4000 showed up on the Grammy Awards red carpet with a 10-foot-long durag that followed behind him like a train for a wedding gown. “That takes a whole lotta fabric,” the MC says with a laugh. Yet, for Guapdad, who says durags give him “special powers” and wears them in music videos, album covers, and pretty much everywhere he goes, it’s the perfect apparel for outsized customization. “[There’s] a sauce from wearing the durag you can’t do with any other headwear,” he says. “It’s funny to take something with so much glamorous form and utility at the same time. That’s dope to me from a design aspect. It’s universal and beautiful.”

The Grammys. New York Times. GQ. The durag is a vehicle mainstream White America has used to chase the Black cool. Black voices on social media, celebrities, and activists have combined to shed decades of negative stereotypes in order to turn an ostracized fabric into a symbol of American hip. Acceptance of the durag has happened on our terms, with us dictating the rules of engagement. This is bigger than the durag itself. It’s about a pivotal shift in American culture, in which Black folks stopped chasing White acceptance and forced White America to either catch up or get left behind.

With anything intrinsically Black, what we love takes on meaning and life beyond its initial intent or use. Black love for the durag is about more than wanting to keep our hair nice for extended periods of time. It’s about more than even fashion. It’s about shedding the cloud of White-dictated respectability that has hovered over us. It’s about loving every part of our expression without restraint, without worry about what anyone else thinks. The durag is a reminder that no matter who we are, what our financial status or living condition, we still take a tiny piece of fabric from our bedside, wrap it on our heads, and go to sleep.

That love wasn’t always out in the open. At the predominantly White college I attended, Crocs, flip-flops, and pajama pants reigned supreme in dorms and classrooms alike — yet I never wore durags in public. I just didn’t feel comfortable, as though anyone in those classrooms would judge me for the durags more than the cornrows they were meant to cover.

So while I understand and respect my Morehouse colleague’s reaction that day, and the desire to honor the historic buildings of an HBCU campus, I love standing in my classroom and seeing my students in durags of every possible color. I love knowing that they don’t have to hide that part of themselves. I love thinking that they can be freer than I was. I love that they have the confidence to know they can still be their best, smartest, most thoughtful selves — without worrying about how they present or the history of that one article of clothing.