Few of Duke University Basketball’s most fervent fans, or haters, I imagine are as knowledgeable of Dr. John Hope Franklin, as they are, perhaps, the contours of Cameron Indoor Stadium. Which is to say, the Black American historian is not necessarily who one thinks of when they think of “The Brotherhood.” Dr. Franklin, who died in 2009, was the author of several books, including one of the most important American history books of the 20th Century, From Slavery to Freedom: A History of African Americans (published in 1947 and now in its 10th edition). Yet Dr. Franklin’s experiences with Duke University and later as a Professor at Duke, might be indispensable to the larger history of the college basketball team that has given the city of Durham and Duke University national, and even international prominence.

At the end of the 19th century, Durham was a small Southern city in North Carolina, which boasted a population of less than 6,000. The city’s fortunes changed with the development of a vibrant tobacco industry — for smoking and chewing — led by the Bull Durham Tobacco Company and W. Duke & Sons Tobacco Company. By 1920, Durham’s population had grown nearly four-fold to more than 20,000.

It was the philanthropy of two tobacco tycoons, Bull Durham’s Julian Carr (which history has revealed as a White Supremacist) and W. Duke & Sons’ Washington Duke that was responsible for North Carolina’s Trinity College’s relocation from Randolph County, NC to Durham; Carr donated the land, that now houses Duke University’s East Campus, and Duke the initial financial endowment. It was Duke’s son, James Buchanan Duke, who created the Duke Endowment, and thus the University in 1924. The Duke Endowment also supports Davidson College (the house of Steph Curry), Furman University, and Johnson C. Smith University, an HBCU in Charlotte, NC.

Surveying the city of Durham in 1912, noted Black intellectual and activist W.E.B. Du Bois celebrated Durham as a city that “characterizes the progress of the Negro American”. In the early 20th century Durham emerged as a model of interracial cooperation in the so-called “New South. As late historian Leslie Brown writes, during a time marked as “the nadir of race relations” — Black Disenfranchisement and the rise of anti-Black mob violence personified in the Wilmington, NC Riots of 1898 — “black Durham emerged as a symbol of black nationalism and black pride…Modern buildings, owned and occupied by African Americans, rose against a backdrop of repression. Nationally, black Durham was viewed as a symbol of what African Americans could do on their own when left alone by whites.”

By “left alone”, Brown was referring to the community of Hayti, which she describes as the “largest and most prosperous of Durham’s black neighborhoods, home to thousands of residents and autonomous black institutions in which they worked, worshipped, shopped, and schooled.” Washington Duke helped build one of mainstays of Hayti’s institutions, St. Joseph’s AME Church, out of a paternalistic desire to maintain the color line in Durham. Washington Duke’s Black barber, John Merrick used the logic of segregation to build a small empire of barbershops for Blacks and Whites, the latter of which allowed him to eavesdrop on his powerful White clientele.

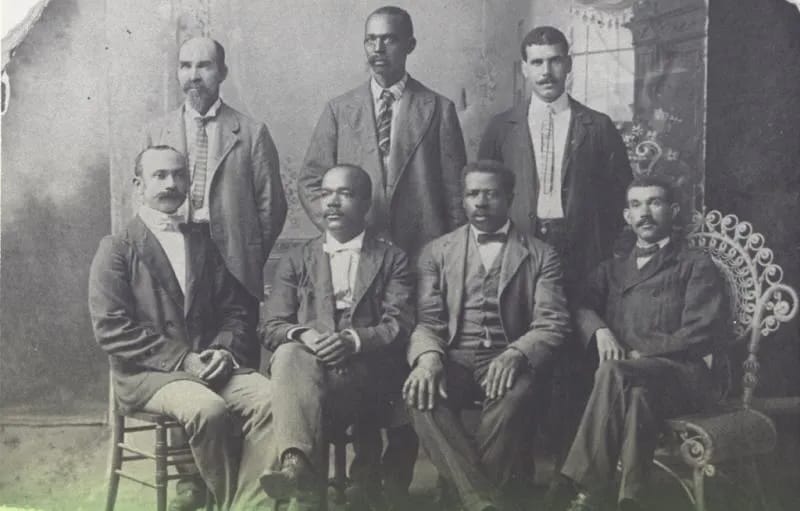

Merrick’s ingenuity and hustle — behind the color line — helped create singular Black-owned institutions like Mechanics and Farmers Bank and North Carolina Mutual Life Insurance, the latter of which was one of the largest Black owned businesses in the early 20th century. If Duke University’s basketball success over that past 40 years might be thought of as the by-product of interracial collaboration — the GOAT White coach and rosters of Black and White players who identify as the Brotherhood — the reality was more complicated.

It was the symbolism of interracial cooperation that John Hope Franklin witnessed in the early 1940s when he arrived at Durham, after a stint St. Augustine’s College, an HBCU in Raleigh, to teach at another HBCU originally known, North Carolina College for Negroes, and now known as North Carolina Central University (NCCU). In his memoir Mirror to America, Franklin recalls an interracial group of scholars at the college, including Ernst M. Manasse, a Jewish refugee from Germany, “who took the initiative in bringing several of us…and several professors from Duke University…together regularly to discuss papers or topics of common interest.” Franklin was also allowed access to Duke University’s library stacks, and recalled conversations with a White Duke professor, Charles S. Sydnor “which always took place in the corridors of the stacks of the Duke library and not in his office, to which he never invited me, I found them, even if intrusive, to be informative and stimulating.”

Important to Franklin’s recollections is the almost secretive aspect of these endeavors: “We always met in a classroom at our college, to avoid embarrassment to anyone who might have felt unable to entertain the multiracial group at his home or at Duke.” Even Franklin’s privilege of researching in the Duke library stacks was a marker of the facade of racial cooperation, where White benefactors were more willing to support the infrastructure of HBCUs, for example, to maintain the myth. North Carolina Central’s B.N. Duke Auditorium, for instance, was named after the college’s largest benefactor in the early 20th Century, Benjamin N. Duke, son of Washington Duke.

A decade earlier, that Julian Abele, a Black Philadelphia-based architect, who designed many of the signature buildings on Duke’s West campus, including the iconic Duke Chapel and the equally iconic Cameron Indoor Stadium, was not allowed on campus to oversee the construction of his designs, because of racial segregation. As Scott Ellsworth writes, “as a colored man, [Abele] would never have been allowed inside to sit and watch a game — let alone attend the building’s formal dedication on January 6, 1940.”

Notable when Franklin writes of these secret gatherings, he asserts, “In its own way, that group was as important in bringing people together as the so-called secret basketball game between North Carolina College and Duke University that was played in [1944] but not widely known of until fifty years later.” The “secret game” was a contest between the North Carolina College’s Eagles and a team from Duke — not the Blue Devils, who won the Southern Conference Championship, precursor to the ACC — but rather a collection of Duke Medical students. There were reasons for the game being secret, even as the Duke team wasn’t an “official” representative of the university. Again, undermining the facade of interracial collaboration, law enforcement in Durham vigorously enforced the color line. Intentionally the game was played on a Sunday morning — in the Bible Beat, most across both sides of the color line were at church.

Ironically, the Blue Devils, “weren’t necessarily the best team on campus.” According to Ellsworth, “The Army and the Navy had established wartime training programs at Duke, and the intramural teams were stuffed with former college athletes.” The HBCU team doubled the White team from Duke that Sunday morning. Perhaps more radically, the teams later combined teams to play a skins vs. shirts game with Black and White players on both teams, according to Ellsworth.

Intercollegiate basketball began at Duke during its Trinity College days, when the team was alternatively known as Trinity Eleven, the Blue and White or the Methodists, before settling on the “Blue Devils” in the 1920s. The first real heyday of Duke basketball occurred during the 14-year tenure of Eddie Cameron, for whom Duke Indoor Stadium was later renamed for in 1972, who also doubled as Duke’s Football coach from 1942–1945, during war time.

Whether Coach Cameron was aware of the “secret game” or not, he was likely very aware of North Carolina College’s coach, John McClendon, who arrived in Durham in the late 1930s. By the time of the “secret game” McClendon was already earning a reputation for transforming the game, introducing the “fast-break” style of play to basketball, replacing the low-scoriang, plodding nature of the sport at the time.

McClendon was one of the last students of Dr. James Naismith, regarded as the “father of basketball.” Ironically when McClendon arrived at Naismith’s homebase at the University of Kansas in 1933, he was joining a student body that had first integrated 50 years earlier. It would be another 19 years after the “secret game” before Duke University admitted Black students — Wilhemina Reuben-Cooke, Mary Mitchell Harris, Gene Kendall, Cassandra Smith Ru, and Nathaniel White Jr. — and three years after that before Claudius C.B. Claiborne became Duke Basketball’s first Black varsity player (and the university’s first Black scholarship athlete). It would be another ten years before Duke would bring in a top Black recruit in Gene Banks, who became Duke’s first Black All-American in 1979. Banks was a member of the 1978 team which made it to the final four and was a member of the team during Coach Mike Krzyzewski’s first year as coach.

The “secret game” was still largely unknown when John Hope Franklin returned to Duke in 1983 as the James B. Duke Distinguished Professor of History — named for the man who provided the initial endowment for the university — and something that would have been unimaginable to Duke and his father Washington Duke in their day. Dr. Franklin’s appointment at Duke coincided with Coach Krzyzewski’s first trip to the NCAA tournament, with a team that featured Johnny Dawkins at shooting guard and Tommy Amaker as point guard. Both Dawkins and Amaker, part of the core of Krzyzewski’s first Final Four team in 1986, became collegiate coaches.

By the time that the story of the “Secret Game” became well known — Scott Ellsworth’s New York Times Bestseller, The Secret Game: A Wartime Story of Courage, Change, and Basketball’s Lost Triumph, was published in 2015 — Bill Bell was serving as Durham’s second African American mayor (he served 16 years!) and the idea of the “Brotherhood” became a recruiting appeal for a dizzying array of McDonald’s All-American and NBA First-Round Draft choices.

Yet despite the prominence of “The Brotherhood” as a contemporary model of interracial cooperation, the program has never had a Black head coach — and I mean this as no shade to current coach John Scheyer — and the brand of The Brotherhood has not necessarily translated into the university being seen as a safe-haven for Black students. Indeed, the success of the program seems disconnected from the race politics of the university or the country.

This was a lesson that C.B. Claiborne learned firsthand; he was benched during his senior year because of his involvement with Black students who took over the Allen Administration Building on Duke’s campus in February of 1969. As Claiborne told an audience in 2019, on the occasion of the 50th Anniversary of the protest, “When I’m asked, ‘Why did you go into Allen building?’ It was because my community was here among the Black students, and I went into the Allen building with my community.”

Duke University has made many amends over the years; among them a portrait of Julian Abele hangs in the lobby of the Allen Building and a monument for Abele was dedicated a few years ago, though students are quick to quip that it’s the only monument at Duke that folk can step on (it’s embedded in the ground of Duke’s main quad.) Duke finally acknowledged Claiborne’s importance to the basketball program in 2023 with a ceremony in Cameron Indoor Stadium, and in 2024, Claiborne received an Honorary Doctorate from the university.