I grew up in Minneapolis, Minnesota. I spent the first five years of my life on the Northside and the remainder of my school years on the Southside. They are vastly different places.

I recently wrote a short book about the contributions of Jimmy Jam & Terry Lewis to the Minneapolis Sound, mentioning Prince, the recently departed Jellybean, with whom I attended high school, and the multiple bands, including those fronted by Morris Day and others. Jimmy Jam grew up on the Southside, only a block over from me. I lived at 4220 Oakland Ave. We shared an alley with Portland Ave., a one-way street carrying traffic from downtown into South Minneapolis. Jimmy Jam lived on 41st and Portland. Renee Nicole Good was killed by an ICE agent on 34th and Portland.

Terry Lewis grew up on the Northside. We crossed paths in high school athletics. He was a couple of years younger, so he was playing on the North High sophomore team when I was on varsity at Marshall-University High. We were both on track teams at the same time, but he was a top sprinter, and I threw the discus. The bands that made up the Minneapolis Sound came together on the Northside. I had to research that community, including The Way Community Center, where many of them practiced. I knew another spot they sometimes played and rehearsed, the Phyllis Wheatley Community Center, because I once lived in the Sumner Field Projects, where the center was located. I went to church on the Northside, attending Zion Baptist Church on Sundays and attending choir rehearsal on Saturdays when I was in my teens. I was exposed to North Minneapolis, but didn’t know it like the Southside.

I knew South Minneapolis because I walked those streets and rode my bike all over them before driving them. An experience I had that my granddaughters will never know: kids walked and ran everywhere. I walked to Field Elementary on 46th and 4th Avenue, to the library on 36th and 4th Avenue. I walked to the three local parks: McCrae Park, where I played T-Ball and baseball, and MLK Park on 40th and Nicollet, where we played basketball at an indoor gym. Phelps Park on 39th and Chicago was for ice-skating when the baseball fields were flooded in winter, freezing over into an outdoor rink. Phelps Park was a block from where George Floyd died, gasping, “I can’t breathe.”

While George Floyd and Renee Nicole Good made national news, Minneapolis, like every other metropolitan city in America, has had its share of violence at the hands of authorities. There were riots on Plymouth Avenue in North Minneapolis in 1967, triggered by the mistreatment of a Black woman at the Aquatennial Parade. In the five years before George Floyd, there were Philando Castile, killed at a traffic stop, and Jamar Clark, allegedly shot while wearing handcuffs. Justine Diamond was shot in her home after calling 911 herself to the scene. People dying at the hands of authorities in Minneapolis isn’t new, though it is unusual that it’s a white woman like Renee Nicole Good.

For six years, I rode the city bus across town to Marshall-University High, transferring downtown in front of Shinders Book Store. I was unaware then of the redlining that shaped the Southside neighborhoods. My maternal grandparents lived on 40th and 5th Avenue. They shared an alley with Portland Ave and were six blocks from where Good would be killed. I didn’t know that Nana’s house was one of the first FHA homes Black people could buy in Minneapolis, and that Black people were allowed to live only past 42nd Avenue, a few years before my family moved there. I attended Field Elementary School, unaware of the battle over its integration a few years earlier, when I started First Grade there.

What I did know from riding the bus was where Black people got on and off. I usually took the #9 bus, catching it on 42nd and 4th Avenue. That stop was almost equidistant from my home as where I could catch the #5 bus on 42nd and Chicago. On my way home from school, I might take either bus and get home about the same time. The route of the #5 has now changed, no longer passing through what is now, The Free State of George Floyd” between 38th and 39th and Chicago.

If you knew South Minneapolis, you might imagine that 34th and Portland was an integrated neighborhood, given it was a stone’s throw from the predominantly Black Central High School on 35th and 4th Avenue. I rode the #9 past Central High and knew that Black people hardly got on after 35th Street. My grandmother took us to Sunday School and Church, always riding on Park Avenue, the one-way street heading towards downtown, two short blocks from Portland Avenue. Portland and Park were once the main thoroughfares before the construction of the I-35W Interstate. Each street is two lanes, with room for parking on both sides.

Unlike some places I’ve lived, like Nashville and Atlanta, that are unprepared for snow, Minneapolis has a system for heavy snowfall. Snow plows hit the streets in darkness. The residents know that, depending on the day of the week, plows are instructed to clear one side of the street, and they don’t park there. If a car is parked on the wrong side, the plow would go around it, creating a short wall of snow and ice that may require the vehicle to be shoveled out.

While the boulevards between the curbs and sidewalks might see snow up to a few feet high by mid-winter, the streets are generally cleared. The videos I’ve seen of 34th and Portland show no signs of recent snow, and I can’t imagine a scenario in which ICE vehicles got themselves stuck, as they claimed. There is eyewitness testimony of a single stuck vehicle, so it seems possible. Still, if it happened, it was likely because the car tried to drive through the boulevard into a yard. Usually, we could refer to body-cam footage, but none of the ICE agents were wearing them. Ice has rolled out body cameras to select cities, excluding Minneapolis, that they won’t name. One could get the impression that the areas with the most activity have the fewest cameras.

For a city of its population, about 430,000 people. Most locations are within easy reach of downtown, especially in South Minneapolis. We have gentrification, but a gentrified neighborhood is as likely to pop up near 50th and Nicollet as on streets between 11th and 36th street. Proximity to downtown isn’t as big a factor as in other cities because everywhere is close.

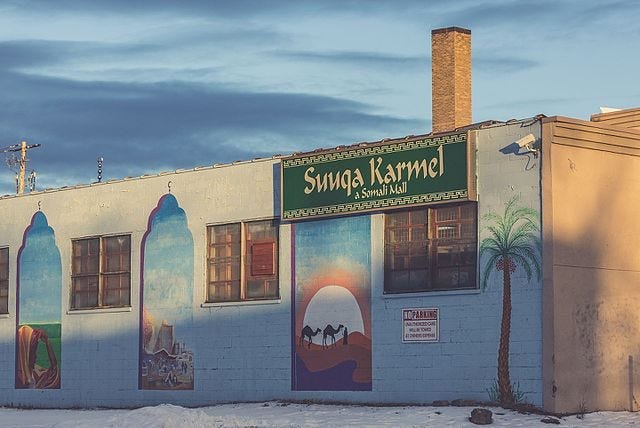

The demographics have changed greatly since I lived there, with an increase in the Hispanic population and the Somalians Trump keeps talking about. The neighborhood near where Good was killed is now about 44% Hispanic, 25% Black, and 21% white. You wouldn’t expect to find Somalians there; they would be in the Cedar-Riverside area and around the Lake Street corridor and Karmel Mall, a few miles East of Portland Avenue. The ICE activity was likely in search of Brown people, not Somalians, almost all of whom are U.S. citizens or in the country legally. ICE would be wasting its time pursuing Somalians.

I had a chance to return to Minneapolis a couple of years ago for a high school reunion. I brought my wife, who’d never been before. We went to Minehaha Falls, Paisley Park, and the Free State of George Floyd. We attended a church service at Zion Baptist Church and shopped and ate at the Mall of America. We drove past my former home, and that of my grandparents, both within a mile of the murders of Floyd and Good.

Truthfully, there is nothing unique about Minneapolis when it comes to the death of George Floyd or Renee Nicole Good. They could have happened in any major city due to the cultures of police departments and ICE, where qualified immunity and bigoted policies render officers and agents almost as immune as the President.

Three things are different this time:

- The City of Minneapolis has experience in the types of protests likely to build for Good because it has a residual infrastructure. It will take less time to organize the resistance, as they already have contact with leaders.

- Donald Trump is emboldened in his second term. This time, he might order federal agents or the military to shoot protesters, which he had talked out of doing in Washington, D.C., protests during his first term. This Donald Trump doesn’t give a damn.

- The victim was white and an American citizen. The President, head of Homeland Security, and the FBI have already labeled her a domestic terrorist, meaning they are ready to expand their war on immigrants to anyone of any color who supports them. The George Floyd protesters weren’t mainly Black Lives Matter members or Antifa; they were white people who are likely to get engaged again. The President’s ego will be hurt, and he will likely attempt to crush protests. This may not end well.

I had a village in the Minneapolis of my youth. When my stepfather died of cancer during my junior year, people stepped up, including and beyond coaches with a vested interest. When I was skipping classes, teachers took an interest. A neighbor who was an administrator at a school other than mine took an interest in me and spoke with me. My pastor and youth pastor followed up. People cared.

Good has a village, too. ICE, Homeland Security, and the President of the United States will soon find that out. The coalition building to support her will come into conflict with forces willing to crush it. ICE had announced it was sending an additional 2,000 people to Minneapolis, even before they escalated things by killing Good. The mayor told Ice to stay out of Minneapolis.

“To ICE, get the fuck out of Minneapolis," he said. "We do not want you here.”

I keep trying to reconcile the Minneapolis in my head with the Minneapolis on the news — the one where George Floyd begged for breath on a street I used to bike down, and where Renee Nicole Good died in the snow a few blocks from my grandparents’ house. But maybe reconciliation isn’t the work. Perhaps the work is refusing to pretend these are separate cities at all.

The truth is simpler and harder: this is my Minneapolis. The music and the murders. The joy and the sirens. The childhood memories and the state violence that keeps rewriting the map.

If loving a place means telling the truth about it, then this is the only love letter I have left to write — one that refuses to look away, one that insists the dead be named, one that demands a city finally worthy of the people who call it home.

Because the Minneapolis I grew up in is gone. But the Minneapolis we fight for doesn’t have to be.