With no disrespect to Al Green, Marvin Gaye and Barry White, Teddy Pendergrass’s voice defined the male soul singer of the 1970s. This claim is as much about the sheer power of his baritone, as it is about the inability to decouple Pendergrass’s impact from that of his record label, Kenneth Gamble and Leon Huff’s Philadelphia International Records (PIR). Hearing Pendergrass’s lead on the Harold Melvin & the Blue Notes, “If You Don’t Know Me By Now,” conjures the aura of refinement and aspiration that was the Philly Soul brand. The single was the first big hit for the label which would dominate Black radio for nearly a decade with a series of hits from The O’Jays, The Intruders, Billy Paul, The Jones Girls, The Three Degrees, Jean Carne and Harold Melvin & the Blue Notes. By the end of the 1970s though, it would be Pendergrass who would be the face of the brand, becoming the most bankable symbol of an imagined Black masculinity during the era.

Born Theodore Pendergrass on March 26, 1950, the singer came of age in Philadelphia, when Motown records began to dominate the pop charts. In contrast to Motor City Soul, Philadelphia was increasingly becoming renowned for its vocal harmony traditions — a sound that Thom Bell would later translate into success with groups like The Delfonics and The Stylistics. Ordained as a minister at age ten, Pendergrass found his vocal inspiration via the example of Marvin Junior, the lead singer of The Dells. As Pendergrass observes in his memoir Truly Blessed (1998), “Marvin Junior’s romantic, soulful voice was a gift from God. He could sing as smooth as honey one moment, then tear out your heart with an anguished plea.”

When Harold Melvin & the Blue Notes signed with PIR in 1971, It was Pendergrass’s vocal affinity to Junior that caught Gamble and Huff’s attention, when they were unable to pry The Dells from Chess Records. Initially Gamble and Huff packaged The Blue Notes with bluesy and lush ballads, the first of which “I Miss You” — deemed too Black by some — was released in March of 1972. With the group’s subsequent “If You Don’t Know Me By Now” and “The Love I Lost,” the Blue Notes became one of PIR’s first major stars, finding success on the dancefloor and in the bedroom, with Pendergrass providing the majority of the leads. Tracks like “Be For Real” — an extended musical dissertation on Black social class divisions, camouflaged as an after-dinner argument between a couple — “Wake Up Everybody” and “Bad Luck” were emblematic of the best of Philly Soul.

Pendergrass’s dominance as lead — folks often assumed he was Harold Melvin — was so palpable that the group’s 1975 album To Be True was branded as Harold Melvin & the Blue Notes featuring Theodore Pendergrass. The tensions led to Pendergrass’ eventual departure from the group in 1976.

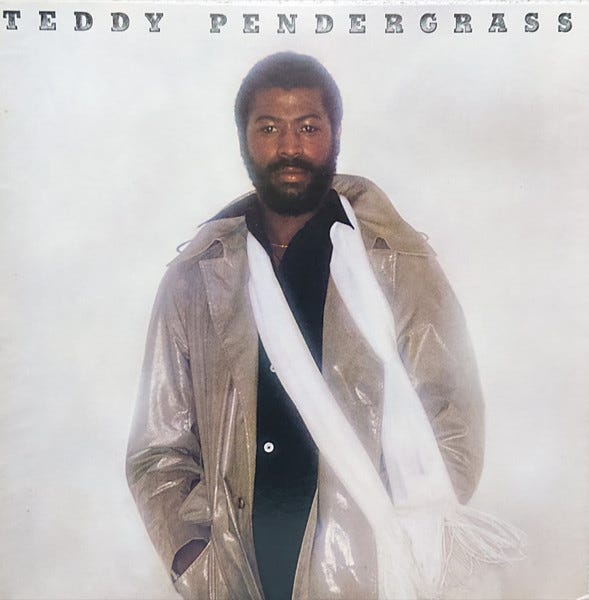

Not everyone was convinced that Teddy Pendergrass would be a successful solo act. One person who had faith in Pendergrass was his then manager Taaz Lang, who told The Philadelphia Tribune, shortly before the release of his solo debut Teddy Pendergrass (1977), that “Teddy has the talent of Stevie wonder, and the sex appeal of a Tom Jones or Johnnie Mathis.” Even if Gamble and Huff weren’t sure how such appeal would translate to audiences, they had no doubt about who Pendergrass was as an artist. As Pendergrass recalled, “It was easy to record and believe in the songs, because they wrote them for me. It’s impossible to describe , but when I sang their songs, they immediately became my songs.”

Aided by Columbia/CBS Records’ “Teddy is Ready” campaign, the lead single “I Don’t Love You Anymore” rode the crest of the Disco wave, though Pendergrass was quick to distance himself from the trend, telling The Amsterdam News, “Disco music is just a craze and I’m about longevity.” Though Gamble and Huff would package Pendergrass with dance tracks like “Get Up, Get Down, Get Funky, Get Loose,” and “Only You,” (which Eddie Murphy later spoofed in his standup routine) on later albums, he largely established himself on his debut with sultry ballads. Tracks like “Somebody Told Me,” “The Whole Town’s Laughing at Me,” and the brooding “And If I Had” were Quiet Storm staples.

In a review of a Teddy Pendergrass concert at New York’s Carnegie Hall in April of 1977, New York Times critic Robert Palmer admitted the singer’s obvious appeal and talent, but cautioned, “his on-going popularity will depend on the songs, productions and packaging the people at Philadelphia International come up with.” Palmer — as astute a critic as there was in the late 1970s — was incapable of seeing what Pendergrass’s cultural appeal was.

Pendergrass would never need the crossover audience that Palmer was alluding to. PIR understood the increasing cultural and economic power of a post-Civil Right era Black middle class that was just beginning to flex its influence — an audience less interested in watered-down cross-over Blackness, but something more authentic. Pendergrass was that voice of authenticity, and the proof was in the sales; his first five studio albums all went platinum or multi-platinum — the first Black male artist to achieve the feat — selling primarily to Black audiences and garnering little if any airplay on mainstream pop stations.

Pendergrass’s popularity as a solo artist lies in his performance of a masculinity that was virile and potent and tailor-made for a cultural discourse that began to move beyond that of the Civil Rights era and fixated on establishing acceptable images of Black masculinity within an integrated society. What made Pendergrass’s performance of Black masculinity so accessible was, in part, the physical limits of his vocal instrument. Never technically strong as a singer — he never possessed the vocal dexterity of his peers Marvin Gaye or Al Green or even the range of Barry White — there was an earnestness in Pendergrass’s baritone that helped soften a hypermasculinity that was off the charts. Still in his late twenties when he became an icon, Pendergrass’s full beard and sonorous voice evoked a man twice his age.

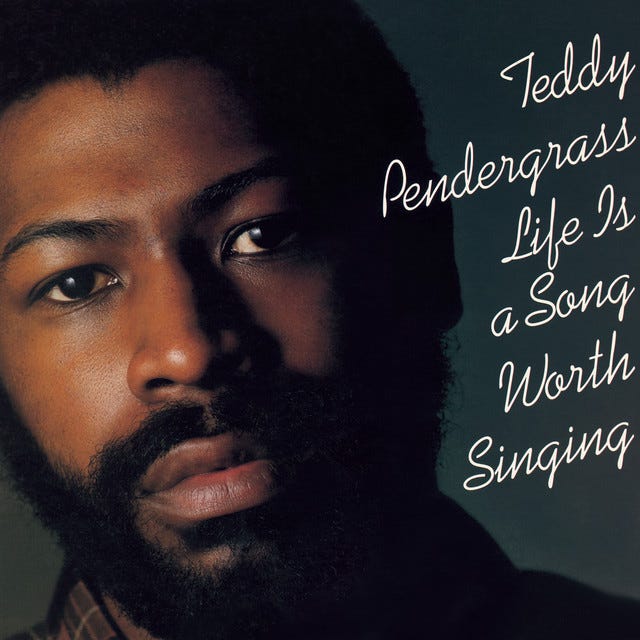

If the “born-again” Al Green was no longer invested in the hyper-sexualized Black masculinity that he and an aging Marvin Gaye (who later saw Pendergrass as a rival) helped cultivate in the 1970s, Pendergrass was a suitable and unequivocally masculine (by the standards of the era) replacement. Though Pendergrass was often ambivalent about his sex-symbol status, telling Amsterdam News reporter Marie Moore in a 1978 interview that “it’s something that sort of happened. I don’t deal with that crazy shit, I’m not like that,” his record company clearly understood this dynamic, choosing “Close the Door” as the lead single for his second solo album Life is a Song Worth Singing (1978). When asked by The Amsterdam News to describe “Close the Door,” Pendergrass simply replied, “panty wetter,” an apt description for many of the ballads on Life is a Song Worth Singing and his follow-up Teddy (1979) including “It Don’t Hurt Now,” “Come On And Go With Me,” and “Turn Out the Lights.”

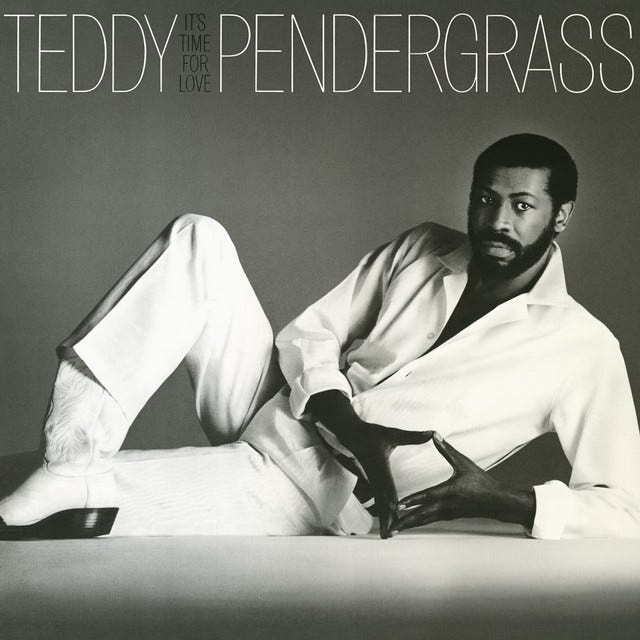

With the release of the multiplatinum Teddy (1979) and Live Coast to Coast (1979) and Pendergrass’ well publicized “women only” concerts, where attendees were given chocolate teddy-bear shaped lollipops (“so that she’ll have something to lick” as quoted in The Amsterdam News), Pendergrass’s musical image was quickly degenerating into the type caricature befitting the 1970s. Pendergrass seized upon the opportunity presented by the deterioration of Gamble and Huff’s working relationship to court with new producers (Dexter Wansel and Cynthia Biggs) and writers, and to begin writing some of his own songs. Pendergrass’s albums, TP (1980) and It’s Time for Love (1981) find the singer at the peak of his artistic powers. “Can’t We Try,” the lead single from TP, and one of the singer’s most exquisite performances was penned by former Motown staffer Ron Miller; Pendergrass handled the production himself.

TP also featured Pendergrass’s first collaborations with the songwriting and production team of Womack and Womack (Curtis and Linda Womack) on the track “Love T.K.O.” and Nick Ashford and Valerie Simpson (“Is It Still Good To You”). Additionally, TP features Pendergrass’s pairing with touring partner Stephanie Mills on a cover of Peabo Bryson’s “Feel the Fire.” Mills recorded the track on her breakthrough album Whatcha Gonna Do with My Lovin’ (1979) and according to Pendergrass, “Stephanie and I were rehearsing for a show when I heard her sing ‘Feel the Fire’…Singing the song to myself as I listened to her belt it out during her soundcheck, I couldn’t help wondering how we would sound performing it as a duet.” The duo returned to the studio a year later to record “Two Hearts,” as Pendergrass noted “our duets were so hot that, as with Marvin Gaye and Tammi Terrell, folks who didn’t know us assumed our passion was more than an act.”

If TP gave indication of Pendergrass pursuing nuance in his recordings, It’s Time for Love (1981) was confirmation of that fact. The introspective lead single, “I Can’t Live Without Your Love” and follow-up “You’re My Latest, Greatest Inspiration” (with Womack and Womack behind the boards) gives the strongest indication of the direction that Pendergrass wanted to pursue going forward. Pendergrass admits in his memoir that “with my fifth studio album…the Teddy Bear was doing more purrin’ than roarin’.” Critics also noted the shift, as Stephen Holden observed in The New York Times: “It was an open question as to whether Mr. Pendergrass could smooth out the roughest edges and develop a ballad style that was anywhere as potent as his ferocious shouting style….the strongest cuts on last year’s TP were all ballads that showed Mr. Pendergrass developing long narrative laments with unprecedented subtlety and emotional conviction.”

Pendergrass supported It’s Time for Love with a tour of England, with Mills, and was primed for the kind of crossover success that had eluded him during his solo career, when a winding road outside of Philadelphia placed his life, his career and his embodiment of an imagined Black masculinity in jeopardy.

This Gift of Life

According to Teddy Pendergrass, it was on his birthday, March 26th 1982, that he first began to grasp the gravity of what had happened, more than a week earlier: “the eight days between the accident and my birthday passed a dark, painful blur…I had no idea where I was, who was in the room with me, what time of day it was, or sometimes even who I was.”. Officially, Pendergrass was driving his 1981 Rolls Royce, late in the evening of March 18, 1982, with a companion Tenika Watson, when he lost control of his car. Pendergrass and Watson were trapped in the car for more than forty-five minutes, with Pendergrass sustaining spinal cord injuries that would leave him paralyzed from below the waist and confined to a wheelchair for the rest of his life. As Pendergrass reflects in Truly Blessed, “In one single stroke, my body had been changed forever in ways that I could not even imagine, much less bear to think about. In my mind, though, I was still the same man I was when I started the drive back to Philadelphia that spring night.”

If Pendergrass could assert that he had faith that he was the same man, as he looked beyond his accident, the same could not necessarily be said about communal faith in the meanings behind that body. If Pendergrass’s hyper-masculine and sexually potent body previously served as a salve for the anxieties produced in the midst of Disco’s decidedly queering of popular music, Pendergrass’s broken body became the site for a new set of anxieties about Black masculinity. The source of that angst was the revelation that Pendergrass’s companion that night, Tenika Watson, was transgender.

Well before there was remotely a politically correct way to address transgendered people in the public realm (as if that’s the case even now), Watson was immediately positioned as some sort of freak. As Watson told The Philadelphia Tribune two months after the accident — which she escaped with minor injuries — “I can’t get over how people treat you, how they turn everything around…what really made me upset was the fact that the papers made me seem as though I was some kind of animal or demon and that I was not a God fearing person.”

With Pendergrass in need of money for mounting medical expenses and PIR struggling in the aftermath of a recession and facing the prospect that their most important asset was literally shelved, Pendergrass’s manager Shep Gordon, located tapes of unreleased recordings that formed the basis for This One’s For You (1982) and Heaven Only Knows (1983). Though John A. Jackson suggests in A House on Fire” that the albums contained “material originally deemed too inferior to release,” some tracks give a clear indication of how Pendergrass was imagining the trajectory of his career.

The eerily titled “This Gift of Life,” the lead single from This One’s For You, had been previously released as the B-side to “Can’t We Try.” The title track to the album was a cover of the Barry Manilow hit, highlighting Pendergrass’s desire to interpret some of the pop standards of the time — a desire first articulated with his cover of Eric Carmen’s “All By Myself” during his 1979 concert tour. Pendergrass’s a cappella performance at the end of “This One’s for You” gives the song a depth that Manilow could have never imagined.

Heaven Only Knows even includes Pendergrass venturing into Country music, with the track “Crazy About Your Love.” The song seems an odd choice for Pendergrass, but it was likely recorded with an eye on the fortunes of country music star Kenny Rogers (another noted baritone from the era), who was crossing over to the mainstream and Black audiences with Lionel Ritchie penned and produced tracks like “Lady” and “Through the Years” — tracks the helped Ritchie establish a mainstream presence when he went solo in 1982.

After a period of rehabilitation, Pendergrass was ready to return to the studio in 1984. With PIR no longer viable, Pendergrass signed with Elektra and released Love Language. Pendergrass’s voice was noticeably “lighter” and much of the production lacked the layers of lushness that was PIR’s signature. The notable exception was Vandross’s production on “You’re My Choice Tonight (Choose Me),” a song that was later featured in the film Choose Me (1985). Love Language was also notable for the pairing of Pendergrass with a twenty-year old unknown named Whitney Houston on the track “Hold Me.” Pendergrass even managed to make a music video for the lead single “In My Time.”

Pendergrass returned a year later with Workin’ It Back, which featured Womack and Womack’s “Lonely Color Blue.” It was during the summer of 1985 that Pendergrass made his symbolic return to the public, performing live for the first time as part of the Live Aid Concerts. The concerts were the product of Bob Geldof’s effort to raise money for famine relief, with performances broadcast from London’s Wembley Stadium and Philadelphia JFK Stadium. Pendergrass appeared alongside his long-time friends Nick Ashford and Valerie Simpson, performing a rendition of their classic song “Reach Out and Touch (Somebody’s Hands).” As Pendergrass recalls, “with Nick and Val on either side of me, I began to weep.”

Pendergrass never looked back. The strength of his voice had largely returned when Joy was released in 1988. Pendergrass eventually earned his first Grammy Award, after three previous nominations, for his 1992 cover of the early Bee Gees classic “How Do You Mend a Broken Heart.” Although Pendergrass never achieved mainstream success, his rendition of “One Shining Moment” — the theme to the NCAA Basketball Tournament — gave him an audience that he could have never imagined. Pendergrass’s last recording was the live From Teddy with Love (2002).

In the aftermath of his accident Pendergrass became an advocate for people with spinal cord injuries, citing the inspiration that Johnny Wilder, Jr. the late lead singer of Heatwave, provided after Wilder became a quadriplegic in the aftermath of an auto accident in 1979. Teddy Pendergrass may have once sung “Life Is a Song Worth Singing,” but in the last 28 years of his life, he proved that his was a life worth living.

Mark Anthony Neal is the James B. Duke Distinguished Professor of African American Studies and Professor of English and Gender, Sexuality and Feminist Studies at Duke University. The author of several books including Looking for Leroy: Illegible Black Masculinities and Black Ephemera: The Crisis and Challenge of the Musical Archive, both from NYU Press. His next book Save a Seat for Me: Notes on American Fatherhood will be published by Simon & Schuster in August of 2026.