I was hanging out with a friend over dinner recently and we started talking about making friends as Black men of a certain age when he debated how much he should lean into his inner unc.

Unc Culture is different than Dad Culture, which comes with dad jokes and dad jeans. Dads come with man caves and retirement funds. We should all sign up for the new pickle ball league and then drop out within a month because the kids’ camp is starting. Unc is less settled.

It’s also different from Black Uncle and Black Dad culture. Unc culture is the casual offshoot. We breeze in and breeze out as if our airy existence is based on how many brews you got in that cooler and how long we gotta man that grill before heading to the next kickback.

It’s the white summertime towel poking out from gym shorts.

It’s the…always being in gym shorts.

It’s having enough wherewithal to give advice but not lecture or dominate the function with your oldhead tales. We don’t need to know where you were for Freaknik ‘99. We know you saw Jordan in the flesh, at the Garden, for the dynasty.

Still being down for the cookout—hosting or attending—bringing good liquor and tree, while staying wise enough to leave early.

Having a new lil thang or two on your arm come Thanksgiving. Somehow single by Christmas.

The uncle is not always a dad, but he might be a father on the loose. A father without a home, so to speak. Between divorces. “Unc” can mean, simply, “unclaimed.” A bachelor over 33 or a divorcé under 55. It’s a range.

I was watching two great depictions of Black Uncle culture this weekend. First, Spike Lee and Denzel Washington’s “Highest 2 Lowest,” which hit all my uncle streams and podcasts seemingly all at once.

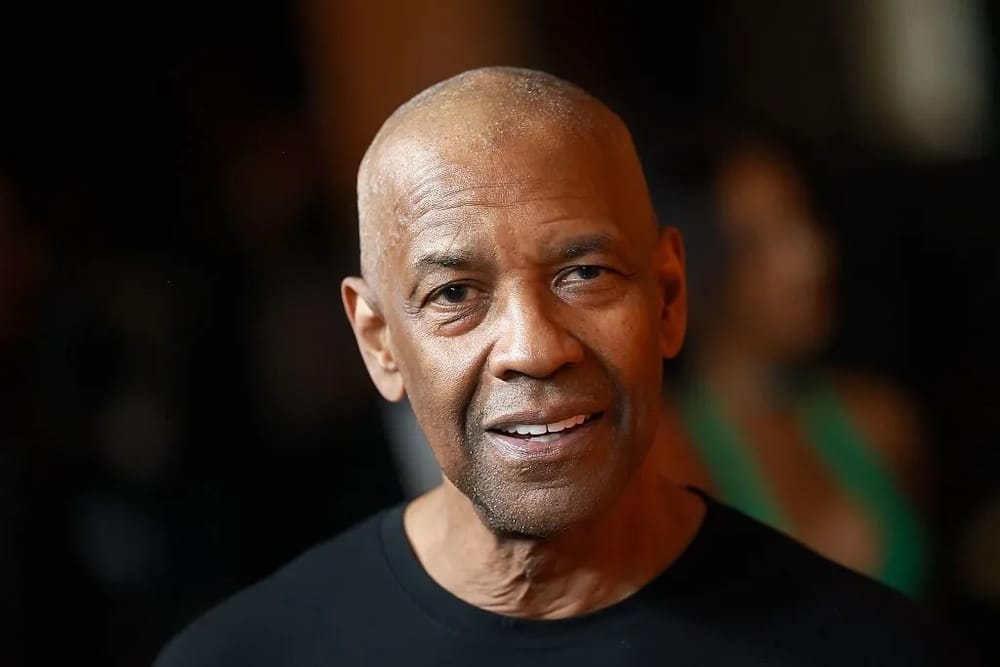

Spike and Denzel are wizened by age and, I have to say, it’s the first time I’ve felt older seeing Denzel look older. His jowls sag more with the bald head he sports, and his eyes have retreated behind fleshy sacks of experience, dragging with them his beauty. He’s still a beautiful soul and a classic face, but the only thing youthful about him is the vigor of his performances. His interview answers also scan like mini monologues as he is a sound bite creature of the highest design.

Spike often garbles his words, animated like a diminutive man would be, but frequently long-winded and meandering. Classic unc-turned-grandpa vibes. Set next to A$AP Rocky, the film’s unjustly pretty co-star, Denzel Washington feels like a relic and an ancestor from which that mold was cut.

The movie’s rich with cultural totems and Black taglines, if about 30 minutes too long. But it’s the unc banter between Jeffrey Wright and Denzel that make it a custom New York film for my particular set. They’re allies; then uneasy brothers; then heroes. They drop jewels and still might be able to whoop some ass when called upon.

Which brings me to the next subtle but beautiful unc portrayal, Martin Lawrence’s “40” in Demascus. The series tracks the title character into a virtual world therapy session where life reshapes an uncanny simulation to match his current unfolding neuroses.

In each simulation, Martin Lawrence as “40” interjects with his avuncular gems. He’s got the earned wisdom of failed kidneys and knife fights. As tragic as it sounds—and the show deals in the small tragedy of men aging into emotional isolation—40 is the comedic caution, a nudge to the main character to take care of himself in community. In one telling simulation, Demascus and Redd, his best friend, are cast as gay lovers. It’s the only time they readily ask for and give each other help.

While it’s not impossible for Black men to seek help among friends, our internal stories cast us the invincible providers of some infinite enterprise. We can’t fail. It’s a sad irony that our Black women partners often feel the same way. That leads to inevitable breakdowns in community care. Everyone’s a hero, no one can be helped, and we bicker over who broke the foundation.

Rather than see myself as an infinitely scaling LLC, I have embraced my inner unc. I am a tree growing and sprouting until I can’t anymore. My organs will bid me farewell only a little at a time. My work will be replaced by someone or something faster or younger. I will become an orphan. The project of emotional security and village-building, however, is its own lifelong reward. And all the uncs have to do is keep showing up, and keep asking for help.