In many ways, New Orleans in 1786 was a unique place in America for Black people. New Orleans had been under French Rule from 1682 to 1763 and under Spanish Rule for over twenty years. American laws like Partus Sequitur Ventrem were adopted in 1724 under the Code Noir, the Black Codes adopted by France to define the conditions of Slavery in French colonies. Code Noir co-existed with plaçage, which defined interracial relationships between white people and either free or enslaved Black people. Plaçage was a structured, socially recognized system unique to New Orleans and coastal Louisiana. These contracts often stated that children born to Black women in these relationships were either born free or manumitted after birth.

Combined with liberal policies like coartación, which allowed enslaved people to purchase their freedom. These conditions combined led to New Orleans having a higher percentage of free Black people than any other location in America. By the 1780s, in some northern cities, such as Philadelphia, up to 15% of the Black population was free. In New Orleans, depending on the parish, the percentage of free Black people doubled that.

In most of the U.S., interracial relationships were hidden, illegal, and socially condemned. In New Orleans, they were common, semi-formal, socially recognized, tied to property and inheritance, and part of Creole identity. The daughters of plaçage relationships became the core of the gens de couleur libres, the free Creole class that shaped the city’s culture.

By 1786, New Orleans had:

- White Creoles

- Free Creoles of color

- Enslaved Africans and African‑descended people

This middle class — the gens de couleur libres — was larger and more socially visible than anywhere else in North America. Free Black women were desirable to both French and Spanish men, and, as a group, they became lighter-skinned over generations. There came a point where light-skinned Black women were often indistinguishable from white women. Their appearance and status challenged the colonial assumption that whiteness was obvious and superior.

While many white people enjoyed the benefits of plaçage, others complained that free women of color were “too luxurious” and too visible. Esteban Rodríguez Miró issued the 1786 Bando de Buen Gobierno (Edict of Good Government) because he believed the social order in New Orleans was slipping out of the colonial government’s control — and free women of color were at the center of that anxiety.

Governor Esteban Rodríguez Miró added the Tignon Law to a law he was already preparing to issue, the 1786 Bando de Buen Gobierno (Edict of Good Government), because he believed the social order in New Orleans was slipping out of the colonial government’s control — and free women of color were at the center of that anxiety.

Miró believed some Black and mixed‑race women displayed “too much luxury in their bearing”. White women pressured him to restrict the fashion and visibility of non‑white women. Historians note that the real purpose was to control women “who had become too light-skinned or who dressed too elegantly, or who… competed too freely with white women for status and thus threatened the social order.” The law was meant to reassert racial hierarchy.

Miró’s goal was to halt plaçage unions, which white elites saw as destabilizing. The tignon was meant to make racial identity visible and prevent women of color from being mistaken for white.

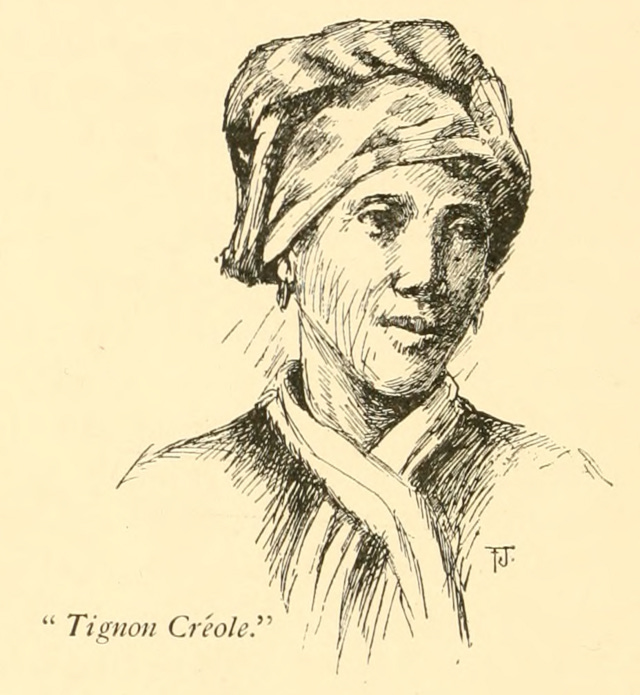

“The Negras, Mulatas, y quarteronas can no longer have feathers nor jewelry in their hair. [Instead, they] must wear [their hair] plain (llanos) or wear pañuelos, if they are of higher status, as they have been accustomed to.”

The law specifically names mulattos, quadroons, and by implication, octaroons and women “sixteenth-part Black,” or more. If the goal of white women was to force Creole women to self-identify with tignons, it was a spectacular fail. White Creole ballroom owners were already organizing “Quadroon Balls” that perpetuated the system of plaçage. The balls were held in public ballrooms, dance halls, hotels, and private assembly halls. Creole women turned their tignons, meant to tarnish them, into fashion accessories highlighting their racial status. The balls existed before the Tignon Law was passed, but exploded in popularity afterward until the 1850s, when American racial laws hardened and legal protections for free Black people receded.

Though Quadroon Balls faded away by the 1860s, the tignon has made a striking return in the 21st century, but in a completely transformed way. What was once a colonial tool of racial control in 1786, New Orleans has become a symbol of pride, heritage, and fashion across the African diaspora. The shift is one of the most powerful examples of cultural reclamation you’ll find in American history.

Today, the tignon is embraced by Black women in Louisiana, Creole communities across the Gulf Coast, African American women nationwide, and Afro‑Caribbean and Afro‑Latina communities. It’s worn as a statement of identity, resistance, beauty, and a connection to ancestors. The meaning has flipped from marking to celebrating.

In New Orleans, the tignon is now part of second‑line culture, worn during festivals like Jazz Fest and Mardi Gras, featured in Creole heritage events, sold by local designers in the French Market, and taught in workshops on Creole history. It’s especially visible in the Tremé, the Seventh Ward, and among families who trace their lineage to the gens de couleur libres.

What happened in New Orleans in 1786 was never just about fabric. It was about a government trying to force a hierarchy back into place at the very moment it was slipping from its grasp. Free, light‑skinned Black women — many of them daughters and granddaughters of plaçage, many of them legally free because of the very laws the colony had created — had become too visible, too successful, too elegant, too close to the privileges white society believed belonged only to itself. The tignon was supposed to mark them, contain them, remind them of a status the law insisted they carry even when their lives told a different story.

But the women themselves refused to shrink. They wrapped their hair in silks and bright colors, tied their tignons high, and turned a badge of restriction into a declaration of presence. In doing so, they exposed the truth Miró’s edict could not hide: that power is never as stable as those who wield it imagine, and that identity cannot be legislated into invisibility.

The tignon law has long since vanished, but the impulse behind it has not. Across centuries, Black women’s beauty, autonomy, and visibility have continued to unsettle the societies that depend on their labor while policing their expression. The story of the tignon is not an artifact — it is a reminder. A reminder that every attempt to control Black womanhood has been met with creativity, defiance, and an insistence on being seen. And that, perhaps, is the real legacy of 1786: not the law itself, but the women who refused to let it define them.