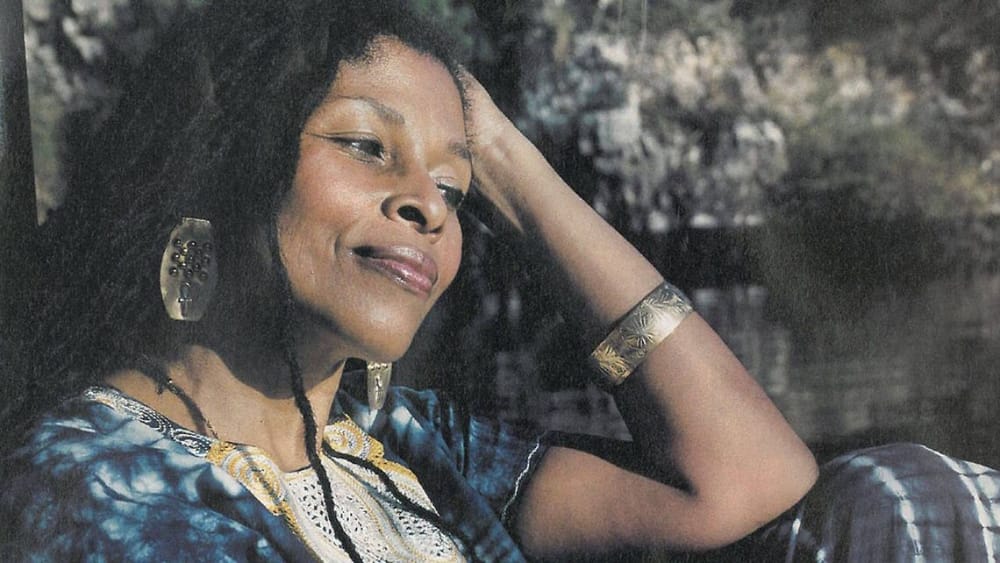

Upon learning that Assata Shakur, the Black revolutionary who spent the last four decades in exile in Cuba, died a free woman this week at the age of seventy-eight, many began to celebrate her legacy. While media outlets often labeled her a terrorist on the FBI's "most wanted list," and government officials offered millions for her bounty over the years, many people see her as a hero, someone unfairly targeted for their political beliefs. Now, as a form of poetic justice, her words, captured in her writings and filmed interviews, are accessible to the public. To understand why so many have chosen to honor her life and fight for freedom, consider her experience—not just as a Black leader, but as someone relentlessly targeted by law enforcement.

Lennox Hinds, an attorney who represented the National Conference of Black Lawyers, the National Alliance Against Racism, and the Commission on Human Rights, described a widespread pattern of human rights violations within the United States. Officials targeted Individuals because of "their race, economic status, and political beliefs." Hinds pointed out that Assata Shakur became a target as part of the "COINTELPRO strategy," in which federal authorities presented "fabricated evidence," and engaged in "spurious criminal prosecutions," to subdue the Black liberation movement. For example, the FBI led a campaign against the Black Panthers' Free Breakfast for School Children Program, looking to destroy rations and criminalize members of the organization despite their community work.

Authorities accused Assata Shakur, born JoAnne Deborah Byron in 1947, of committing a litany of crimes. In New York, they claimed she took part in an armed robbery in April of 1971, but the charges were later dismissed due to lack of evidence. Prosecutors accused her of taking part in a robbery in Queens during August 1971, but she was acquitted of these charges. Then, U.S. Southern District of New York City officials claimed Assata took part in a bank robbery in September 1971. The case resulted in a hung jury, and when prosecutors tried again, the case resulted in an acquittal. While her opponents portray Assata Shakur as a wanton criminal, a pile of acquittals and dismissals points to an unjust system, one desperate to incriminate a Black woman.

Sadly, this list of criminal charges was only the tip of the iceberg, as government lawyers continued to accuse Assata Shakur of committing heinous crimes. They charged her with kidnapping a drug dealer in December 1971, but she was acquitted. Next, they accused her of killing a drug dealer in 1973, but those charges were dismissed. The same outcome occurred when prosecutors in Queens County, New York, accused Shakur of attempted murder of police officers. Their overzealous pursuit of Assata Shakur was not unrelated to her role in the Black Panther Party and later the Black Liberation Army. It was because of her beliefs that they relentlessly investigated her.

After years of investigating Assata Shakur, prosecutors finally succeeded in bringing her up on charges that stuck, in a legal sense. They accused her of killing a state trooper along the New Jersey Turnpike. Her defense team argued that the injuries she sustained made it impossible for her to have been the shooter, as she had her arms raised in surrender when she was fired upon. Prosecutors didn't present any evidence, such as gunshot residue or fingerprints, to prove she fired a weapon. Still, the all-white jury convicted Assata in 1977, and a judge sentenced her to life in prison. Two years later, some members of the Black Liberation Army helped her escape by posing as visitors. She would later seek political asylum in Cuba, where she would spend the rest of her life, free but in exile. She once referred to herself as a "20th-century escaped slave" because of the bounty government officials placed on her head. Given the nation's history, this comparison seems fitting.

When imprisoned, Assata Shakur endured harsh conditions. She received inadequate healthcare after suffering physical trauma, was routinely isolated from other inmates, and had limited time to speak with her attorney and family members. Even during her pregnancy, Assata had to advocate for quality care. She spent at least twenty months in solitary confinement in two separate men's prisons, as well as time in mixed and women's only prisons. In Hinds' report, he noted, "she has never on any occasion been punished for any infraction of prison rules which might in any way justify such cruel and unusual treatment."

Far too often, Black defendants are denied proper legal counsel. Sometimes, all or mostly White juries assume Black defendants are guilty, while judges tend to impose harsher, longer sentences for Black people. One study published in the Quarterly Journal of Economics found that all-white jury pools convict Black defendants 16 percent more often than White defendants. So, while an all-white jury claimed Assata was guilty of the crimes prosecutors accused her of, many of her supporters believe their decision was biased, one affected by her race, gender, and political beliefs. This is essential context, as some conservatives are claiming that those on the left are celebrating someone who killed an officer. Those who consider Assata Shakur a hero believe she has been unfairly persecuted. Fidel Castro, a Cuban revolutionary and political leader, once referred to her as a "true political prisoner" of the United States.

“Throughout amerika’s history, people have been imprisoned because of their political beliefs, charged with criminal acts in order to justify that imprisonment,” Assata Shakur wrote.

Law enforcement officials arrested and, in some cases, killed members of the Black Panther Party. In 1968, Oakland police killed Bobby Hutton, the party's first treasurer and recruit. And, in the following year, Chicago police killed Fred Hampton and Mark Clark, leaders of the party, during a pre-dawn raid. In 1976, the FBI's counterintelligence program that targeted the Black Freedom Movement ended, with a Senate committee saying their actions were "indisputably disregarding to a free society" and "gave rise to the risk of death and often disregarded the personal rights and dignity of the victims." But the damage was done, as many Black people were harmed through the process. Also, the litany of charges made against them perpetuated racist stereotypes in the eyes of the public, portraying Black people as more likely to engage in criminal behavior.

Assata suffered injuries from New Jersey state troopers in May of 1973, as a bullet pierced through her left shoulder and shattered her clavicle. "Doctors testified Shakur's bullet wounds were likely consistent with her hands being raised." Yet, this evidence didn't make a dent in the jurors' preconceived notions.

"Black revolutionaries do not drop from the moon. We are created by our conditions," Assata wrote. As long as racism deprives Black people of equal rights and liberties afforded to others, then there will always be the need for a resistance movement, which Shakur referred to as a Black Liberation Army. I wish I could say that what happened to Assata Shakur, the unfair nature of the trial she endured, and her persecution for political beliefs, was an outdated threat. However, the Trump administration has signaled its interest in targeting Americans based on their political beliefs.

A memorandum entitled, "NSPM-7," directed the Secretaries of State, Homeland Security, and Treasury, as well as the Attorney General, to "coordinate and supervise a comprehensive national strategy to investigate, prosecute, and disrupt entities and individuals engaged in acts of political violence and intimidation designed to suppress lawful political activity or obstruct the rule of law." This includes "entities" that hold various beliefs such as "anti-Americanism, anti-capitalism, anti-Christianity, support for the overthrow of the U.S. government, extremism on migration, race, or gender, hostility toward those who hold traditional American views on family, religion, or morality." In this political environment, even speaking about the ills of racism as Assata did is enough to make someone a target of spurious investigations.

Assata Shakur was a freedom fighter, someone who believed that "Nobody in the world, nobody in history, has ever gotten their freedom by appealing to the moral sense of the people who were oppressing them." Far too often, those who endure injustice are deprived of agency, their voices smothered out by those in positions of power. We saw this during the chattel slavery era when Congress members were gagged and prevented from reading or considering petitions from enslaved people. Fredrick Douglass, the famed abolitionist, suggested, "Power concedes nothing without a demand. It never did, and it never will." It's no wonder that enslaved people participated in at least 250 uprisings before the Civil War. Grossly unsatisfied with their conditions, many liberated themselves. When White colonists rebelled against the British monarchy, historians described their crusade as heroic. However, Black men like Charles Deslondes and Nat Turner, leaders of enslaved people's uprisings, were often portrayed as criminals, if they're mentioned at all.

Research suggests racism persists in America's criminal justice system. The Prison Policy Initiative found that the per capita arrest rate for Black Americans was more than twice the rate for White Americans. This suggests that our system is not as fair and impartial as some claim. A report published by The Death Penalty Information Center found that Black people were 7.5 times more likely to be wrongfully convicted of murder than White people, a risk that was greater if the victim was White. America, the same country that boasts of freedom and democracy, has a reputation for treating Black people as second-class citizens. Indeed, many Black people have endured punishment without committing any crime at all.

Assata's remaining free is like a silver lining in an otherwise gray sky. And while those who personally knew the godmother of Tupac Shakur and the mother of Kakuya Shakur will surely feel grief in her absence, hopefully, her memory will bring them some comfort. In her autobiography, she wrote, "It is our duty to fight for freedom. It is our duty to win," words that now seem to encourage future generations to carry the torch. And at a time when free speech in America stands on shaky ground, and anti-racists risk being targeted for their political beliefs, Assata's narrative is more than historical; it's also painstakingly relevant to what Black Americans are experiencing in the modern era.

This post originally appeared on Medium and is edited and republished with author's permission. Read more of Allison Gaines' work on Medium.