In the introduction to Tricia Rose’s seminal book Hip Hop Wars: What We Talk About When We Talk About Hip Hop — And Why It Matters, she laments that the national paranoia around the art form has robbed the culture of artistic validation — and worse, strengthened the conditions that fueled its urgency. “In this climate,” she writes, “young people have few … honest places to turn to for a meaningful appreciation and critique of the youth culture in which they are so invested. The attacks on black youth through hip hop maintain economic and social injustice.”

Unfortunately, not much has changed about the world or the business of hip-hop in the 13 years since Rose’s book dropped. The largely still White-controlled industry of rap is marketed even more through the apertures of misogyny, self-destructive behaviors, and unapologetic greed. And somewhere out there roam the rap moguls of the universe, building and swapping Black culture like house flips.

Hip-hop has always had room on its stage for different sensibilities, even from the beginning. There have always been rappers who prove the exception to whatever marketing rule was in place at the time. Wherever there was a Kurtis Blow party jam, there was a delightfully gruesome Just-Ice bleacher beater. NWA and X-Clan debuted within a year of each other. Big Boi and Andre 3000 co-existed on six albums. Contrast needn’t be contradiction.

To the music’s detriment, that duality has largely been reduced over and over again to a pissing contest over who is the most hardcore. Work that strives for different values has to work twice as hard to break through. Fortunately, rap has never been all of any one thing, and sometimes genuine concern finds a way. So let’s be clear from the outset what I’m not making a case for: a checklist of soft rappers. I have no dog in a battle over whose hip-hop masculinity is more toxic. This isn’t a compendium of cats who aren’t gangster or can’t handle themselves in a barroom brawl with Nicki Minaj. This is a celebration, an overarching look back at who loved us upon a time, and who may still do so now; rappers who, for a moment in time, really wanted your life to be better and wrote a song to prove it. With all of the rapitalists currently using “the culture” to build up shovel-ready brands, only to sell them off to the highest White bidder, a little reflection on the moments when rap cared about your well-being doesn’t seem like a bad idea.

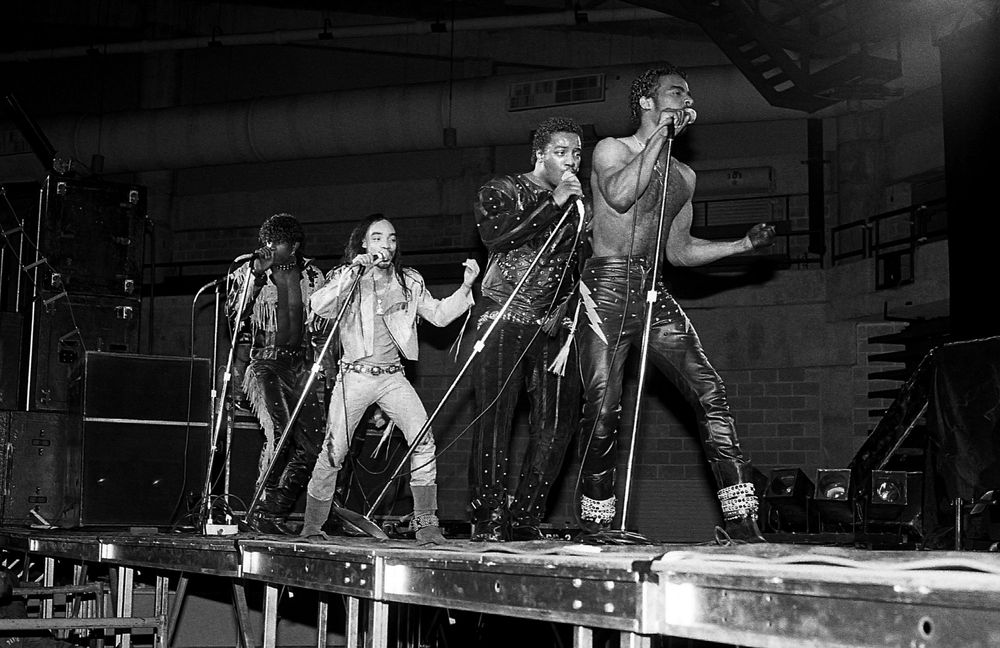

Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five “The Message” (1982)

Released at the ramp-up of the Reagan era, this song was the hip-hop equivalent of Marvin Gaye’s album What’s Going On?: A still-funky socially relevant artistic statement that captured its time while still being ahead of it. “The Message” cut through the party line of good time rhymes, opting instead to give voice to people the evening news wouldn’t touch. The group would repeatedly mine this vein to lesser effect — maybe because the man who had written their anthem had retired from the game — but “The Message” set a bar for conscious rap that still hovers above the field.

Kool Moe Dee “Go See the Doctor” (1986)

Why is my thing-thing burning like this?

Do you know how hardcore you have to be to put your own genitalia on the table in a rap song in an unflattering way? Moe Dee made a case for safe sex in hip-hop before anybody knew they were allowed to write songs about the act. This song is like having your boy being extremely real with you before you go to that house party that will otherwise end poorly.

LL Cool J “I Need Love” (1987)

The GOAT of rap love songs. LL had just dropped what was perhaps the hardest rap song anyone had ever heard (“I’m Bad”) the month before this came out; maybe an ode with such blinding sensitivity could only have come from the cat who was on the throne. The message was clear: Being a real man isn’t all about stepping on Oreo cookies. Sometimes you have to open yourself up to get the finer things in life, like an earnest love.

MC Lyte “I Cram To Understand U (Sam)” (1987)

Released when the emcee was just 16 years old, “Cram” managed to deliver both hard-won relationship wisdom and anti-drug awareness. When you consider that Lyte dropped this at a time when not being the target of macho derision was an alien concept, the storytelling flow of this cautionary tale doubles as a self-respect mantra.

Stop the Violence Movement “Self Destruction” (1989)

West Coast Rap All-Stars “We’re All in the Same Gang” (1990)

These two ensemble jams hit right as the waxing of gangster rap met the waning of conscious rap. For a brief moment in the year between these two songs, it almost felt like hip-hop could change the world. It was a time when rappers were attempting to create actual social movements, though most didn’t last very long. The songs ring a little naive now, but back then it was a big deal to see rappers who were perhaps not cool in real life uniting for a cause we could all relate to — and for what we were sure was almost zero money. It felt like they were in the movement with us.

Kanye West “Jesus Walks” (2004)

Including this one breaks a personal rule for me. I am not prone to giving West props on principle. But before the MAGA hat and public meltdowns, West took a few years to pen this classic and more genuine prototype of the musical faith-wrangling he commits now. He wasn’t the first rapper to insert questions of belief into their work, but he is probably the one who most successfully — and firmly — thrust it into the mainstream on his own terms.

J. Cole “Be Free” (2014)

This haunting song was released on the heels of the killing of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri. Compared to a lot of the literal and aesthetically romantic content of his catalog, this one sticks out for its chant-like delivery and politic. Cole did not avail himself with as much aplomb last year during the George Floyd protests, getting caught up in an unwinnable beef with Noname, but his 2014 effort reminds us that we’re all just trying to feel our way to the right answers.

Kendrick Lamar “Alright” (2015)

The hook of this struggle anthem alone got many of us through a year when Black lives seemed very much in season. Still raw a year after the Michael Brown shooting, in 2015 America was hit with the death of Freddie Gray at the hands of a Baltimore police. Kendrick would release “Alright” as a single two months later, and its lyrics — shouted at protests throughout the country — charged the ongoing demonstrations with hope.

Drake “God’s Plan” (2018)

Drake amplified what was otherwise an anemic take on faith by shooting a companion video in which he spends its entire budget — just under a million dollars — on random acts of charity. Unsuspecting people and organizations become the recipients of random shopping sprees, enormous donation checks, free toys, and wads of cash. Did he later shoot a video that’s basically just a Zillow ad? He did. Will Certified Lover Boy, whenever it drops, continue whatever shreds of altruism “God’s Play” displayed? Probably not. Yet, “God’s Plan” remains the single best use of a musical hook as the inspiration for concrete, grassroots change in recent memory.