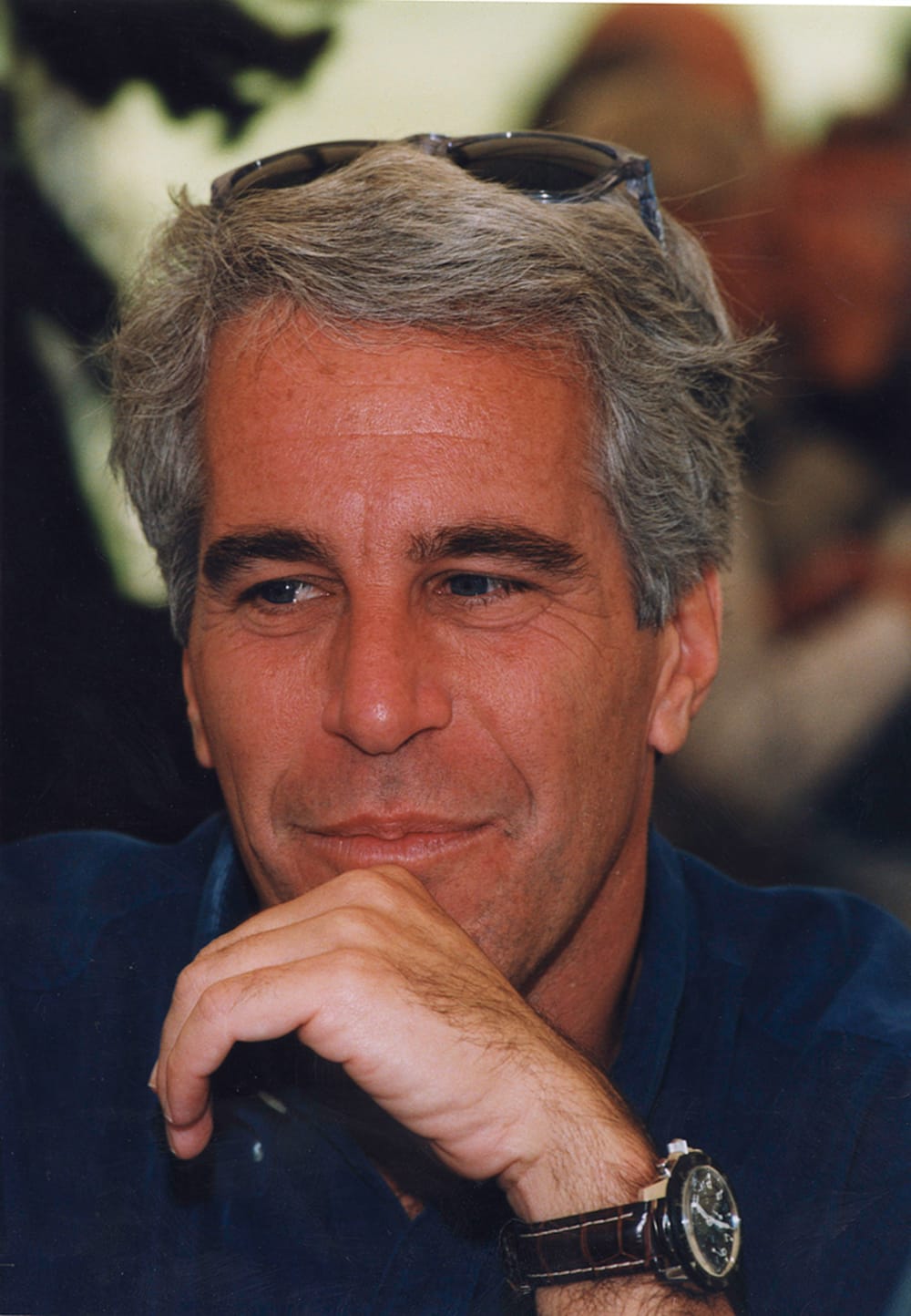

America has always had men like Jeffrey Epstein. What changes across the decades isn’t the behavior — it’s the architecture that protects it. From the Gilded Age forward, the United States built a lattice of legal loopholes, institutional silences, and elite networks that allowed wealthy men to exploit vulnerable young people with near‑total impunity. The story isn’t about individual monsters. It’s about the system that made them possible.

This is the first half of that story — a century of patterns that repeat with eerie consistency. In the decades before the 1870s, wealthy men had legal access to enslaved women, as the rape of a slave wasn’t a crime. Enslaved women could not refuse, testify, or seek protection.

During slavery, forced breeding and rape were a business, designed to meet the needs of the workplace through domestic breeding. In areas with no slavery, indentured servants and apprentices had some legal protections, but were facing a vast power differential. Rich men held all the cards then, and they do now.

1870s — The Gilded Age Blueprint

The 1870s mark the beginning of America’s modern wealth class. Industrial fortunes exploded, cities swelled, and the law lagged far behind the realities of urban life. In this decade, the first documented patterns emerge: wealthy men exploiting minors in environments where poverty, immigration, and child labor create endless vulnerability.

Age‑of‑consent laws in many states set the age at 10 or 12, a legal framework that effectively sanctions exploitation. Urban vice commissions in New York, Boston, and Chicago begin reporting cases of “gentlemen” frequenting brothels where girls are barely in adolescence. Police corruption is endemic; officers were paid to look the other way, and newspapers rarely printed the names of elite offenders.

1880s — Industrial Wealth Meets Urban Vulnerability

By the 1880s, America’s cities were bursting with new arrivals — immigrants, rural migrants, and children working in factories or domestic service. Investigative journalists uncovered brothel networks supplying minors to businessmen and political bosses. Reformers document cases where wealthy offenders are quietly released while poor men face harsh sentences for similar crimes.

Philanthropic “rescue homes” for girls keep detailed records of abuse, but the names of wealthy perpetrators are often redacted or replaced with euphemisms like “a man of standing.” The legal system is not designed to protect minors; it is designed to protect reputations.

Rescue homes in the 1880s were owned and controlled by middle‑ and upper‑class reformers, churches, and wealthy male philanthropists. They claimed to ‘save’ girls, but they operated as institutions of moral discipline, not empowerment. The machinery of protection became more sophisticated, and the victims more invisible.

1890s — The First National Scandals

The 1890s brought the first national conversation about elite sexual exploitation. Journalists exposed trafficking rings in major cities, revealing how minors are moved across neighborhoods — and sometimes across state lines — to serve wealthy clients.

Reformers push to raise the age of consent, explicitly citing cases where powerful men evade prosecution because the law defines a child as a consenting adult. State legislatures debate reforms, but the resistance is fierce. Business interests argue that raising the age of consent will “criminalize respectable men.”

New York held its Committee of Fifteen Investigations, which conducted undercover investigations into brothels and disorderly houses. Their reports documented:

- Minors trafficked to “men of standing.”

- Brothels were operating openly because the police were bribed.

- Girls as young as 13 were forced into prostitution.

4. Elite clients whose names were removed from public reports.

The protection of wealthy men was no different then as it is now, where an Epstein client list has yet to see the light of day.

1900s — Early Hollywood, Railroads, and Political Machines

The turn of the century introduces new industries — film, railroads, mass entertainment — and with them, new concentrations of power. Early Hollywood is a closed world where studio bosses control the careers of teenage actresses. Political machines in cities like New York and Chicago protect wealthy donors from scandal.

Railroad barons and industrialists appear in vice reports tied to underage prostitution networks. Private detectives, hired by corporations and political bosses, specialize in suppressing scandals before they reach the press. Gossip columns in publications like Puck and Judge were full of innuendo about wealthy men and young girls, but then, as now, they weren’t willing to name names.

1910s — The Mann Act and the Federalization of Morality

The Mann Act of 1910, passed amid the “white slavery” panic, is intended to combat trafficking. Instead, it becomes a tool used unevenly and often unjustly. Federal cases reveal interstate trafficking networks serving wealthy clients, but prosecutions disproportionately target poor men and Black men, while elite white offenders evade charges through political connections.

Black Heavyweight Champion Jack Johnson was arrested twice on Mann Act charges. The existence of a Black Champion who had beaten white men for his crown infuriated many people. When they couldn’t find a “Great White Hope” to beat Johnson in the ring, they charged him because he’d flaunted white women in their face.

Investigative commissions document how philanthropy becomes a new form of protection. Wealthy men donate to charities, churches, and civic institutions that, in turn, shield them from scrutiny. The public sees moral reform; behind the scenes, the old patterns continue.

The federal government now has the tools to intervene — but rarely uses them against the powerful.

1920s — Hollywood, Wall Street, and the Roaring Twenties

The 1920s were a decade of excess. Hollywood becomes a global cultural force, and Wall Street fortunes soar. Both industries generate documented cases of minors being exploited by powerful men, but the mechanisms of concealment grow even stronger.

Studio fixers, private investigators, and friendly police departments bury scandals involving underage performers. Wall Street elites use private clubs and “gentlemen’s apartments” where minors are trafficked. When police raids occur, the names of wealthy clients vanish from reports.

The press, increasingly dependent on advertising from film studios and financial firms, avoids stories that could damage powerful industries.

The pattern is unmistakable: the richer the man, the more invisible the crime.

1930s — The Great Depression and Institutional Silence

The Great Depression reshaped American life, but not the underlying dynamics of exploitation. Youth homelessness rises, creating new vulnerabilities. Social workers and juvenile courts document cases involving wealthy benefactors exploiting minors, but records are sealed or anonymized.

Private schools, churches, and youth organizations quietly remove staff after allegations involving minors, often relocating them to new positions without public disclosure. Hollywood’s studio system becomes even more centralized, with contracts, morality clauses, and private detectives used to bury scandals.

The 1930s solidify a culture of institutional silence. The mechanisms of protection — sealed records, private settlements, internal investigations — become standard practice.

By the 1940s, the United States had already built a century of habits around protecting wealthy men from accountability when minors were involved. But the modern era didn’t simply inherit those patterns — it refined them. New institutions, new technologies, and new forms of wealth created even more sophisticated ways to hide exploitation. Here is how impunity matured.

1940s — War, Mobility, and Expanding Networks

World War II reshaped the country. Millions of Americans moved across states and continents, and with that mobility comes new vulnerabilities. Youth homelessness spikes in port cities. Federal agencies document trafficking routes involving minors, but the focus is on “morale,” not protection.

Military police and early FBI files contain cases where elite suspects are quietly dropped to avoid political embarrassment. The logic is familiar: the war effort must not be tarnished by scandal. Hollywood, now a global propaganda engine, becomes even more insulated. Studio bosses, directors, and powerful intermediaries operate behind a wall of patriotic necessity. The war years reveal a truth that will echo for decades: national priorities often override the safety of the vulnerable.

1950s — Respectability Politics and Hidden Abuse

The 1950s are remembered as an era of stability, but beneath the surface lies a culture of silence. Suburbanization and “family values” create a façade of moral order that institutions are desperate to maintain.

Private schools, churches, and youth organizations develop internal processes for handling abuse allegations — almost all designed to avoid publicity. Juvenile courts seal cases involving wealthy defendants. Newspapers refuse to print stories that might disrupt the image of postwar prosperity.

The victims are often blamed or dismissed. The perpetrators are described as “pillars of the community.” The institutions prioritize reputation over truth. The 1950s perfected the art of quiet removal — transferring an accused man to a new city, a new school, a new parish, without ever acknowledging the harm.

1960s — Social Upheaval and Media Blind Spots

The 1960s brought a cultural revolution, but not for the children most at risk. The sexual revolution loosens norms for adults, but minors remain unprotected. Runaways flock to cities like San Francisco and New York, where sociologists document older, wealthy men exploiting them in exchange for shelter, food, or drugs.

Investigative journalists begin uncovering cases involving political donors and entertainment figures, but editors kill stories to avoid libel suits. Media consolidation means a handful of executives decide what the public is allowed to know.

Universities quietly handle cases involving faculty and underage students. The pattern is unchanged: institutions protect themselves first. The decade proves that cultural change does not automatically translate into structural protection.

1970s — The First Cracks in the Wall

Watergate-era skepticism transforms journalism. Reporters begin questioning the institutions that once seemed untouchable. Exposés reveal cover-ups in schools, churches, and youth organizations. Civil suits involving wealthy defendants become more common, though many end in sealed settlements.

Hollywood and the music industry face early public scrutiny for relationships with underage performers. The public begins to see the outlines of a system that has been operating for a century.

But even as the truth surfaces, the consequences remain limited. Wealthy men hire better lawyers. Institutions hire better publicists. The machinery of protection adapts. The 1970s introduced accountability as a possibility — but not a guarantee.

1980s — Money, Media, and the Rise of NDAs

The 1980s are a turning point. Deregulation, Wall Street wealth, and the explosion of private capital create a new class of ultra-rich men with unprecedented access to legal and media resources.

Non-disclosure agreements become a standard tool for silencing survivors. Reputation management firms emerge, specializing in burying stories before they reach print. Private investigators intimidate witnesses. Lawyers negotiate settlements that seal records indefinitely.

Youth homelessness rises, creating new vulnerabilities exploited in documented trafficking cases. Federal agencies uncover networks serving wealthy clients, but prosecutions remain selective. The 1980s mark the shift from institutional silence to legalized silence. The system no longer relies on shame or secrecy — it depends on contracts.

1990s — Globalization and the Internet Era

The 1990s brought globalization, international travel, and the early internet. Wealthy Americans now have access to global networks, and federal investigations document international trafficking routes that mirror earlier domestic patterns.

Civil suits reveal how philanthropy becomes a tool for reputation laundering. Wealthy men donate to museums, universities, and charities that, in turn, shield them from scrutiny. Media consolidation means fewer gatekeepers, but also fewer independent investigative outlets.

The early internet exposed some cases but also created new avenues for exploitation. Survivors begin to find each other online, forming the first digital support networks capable of challenging institutional silence. The decade shows how global mobility expands opportunities for exploitation, while the legal system struggles to keep up.

2000s — The Epstein Template Fully Forms

By the 2000s, the architecture of impunity is complete. Private wealth reaches levels unseen since the Gilded Age. Hedge funds, tech fortunes, and global finance create a class of men who operate beyond traditional oversight.

Federal and state investigations document cases where wealthy men use private jets, private islands, shell foundations, and elite social networks to access and traffic minors. Law enforcement agencies face criticism for lenient plea deals and deferred prosecutions involving elite defendants.

Civil suits reveal long-running networks of enablers: lawyers, fixers, recruiters, publicists, and institutions that looked the other way. Survivors use the internet to bypass traditional media gatekeepers, forcing long-suppressed cases into public view.

The Epstein case is not an aberration. It is the logical culmination of 130 years of structural impunity — a system built layer by layer, decade by decade, to protect the powerful at the expense of the vulnerable.

Conclusion — The Pattern, Not the Man

When you trace this history from the 1870s to the 2000s, a single truth becomes impossible to ignore: America not only failed to stop men like Epstein, it built the conditions that allowed it to thrive.

The mechanisms changed — from corrupt police to sealed court records, from studio fixers to NDAs, from political machines to global networks of wealth — but the outcome remained the same. Vulnerable young people were exploited. Wealthy men were protected. Institutions prioritized reputation over justice.