On a chilly day in March 2022, Grant Williams stepped out of his Infiniti SUV and walked through the snow and hail to the middle of the basketball court in the Stapleton projects to see the new Wu-Tang Clan “W” emblem painted at its center. The logo was yellow against the black asphalt, the same colors used on the group’s first album. The design was laid down in the fall, but Grant hadn’t seen it. As the road manager for Wu-Tang Clan’s Ghostface Killah, Grant spent weekdays working from home booking flights and calling promoters and weekends on tour.

“We [Grant and Ghostface] always had this plan and we were gonna do some type of music together,” Grant said.

COVID-19 made touring over the last two years a stop-and-start affair. “We only have a few dates left,” he said. “I wish I was back on the road so I could just knock it out.”

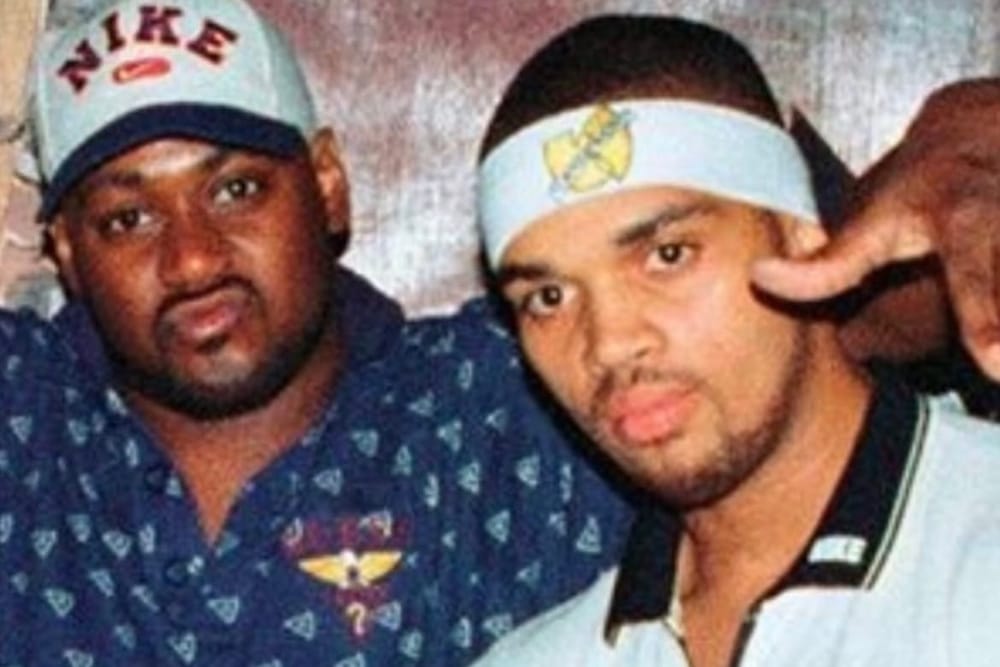

The pause gave him a chance to go back to Staten Island, catch up with old friends, and visit the housing project where at 11 years old, he met Dennis Coles, aka Ghostface Killah. “My mother and his mother; his family and my family, we've always been tight,” Grant said. “Me and Ghostface are more like brothers.”

On the benches, which used to line the courtyard inside Stapleton, Grant says he and Ghostface once sold crack. On those same benches, the two gathered the raw material for what would become one of the most heralded rap careers in the genre’s history. With Grant by his side, Ghostface began to stitch together arresting narratives of growing up in poverty and selling crack to survive.

At eye level, Stapleton in the winter of 2022 didn’t look special. Just another collection of unadorned, government-owned and -operated buildings. It is mid-century brutalist efficiency—bricks, mortar, cinder blocks, and almost no flare. The outdoor breezeways, fronted by metal fencing, connect the apartment to the elevators in the middle of each building.

“It looks like a prison with the tiers. Prison looks just like this,” Grant said.

But it was from these projects, and nearby Park Hill apartments, that Wu-Tang Clan emerged. Their rise in the hip-hop world was both improbable and unprecedented. The group wasn’t a spin-off of an established rap crew, and no hip-hop act blessed them with a guest appearance to help launch their career. The bulk of the clan hail from Staten Island, which was not exactly a breeding ground for early rap music like the South Bronx, Harlem, or Queensbridge. “Wu-Tang was able to see what was going on in other boroughs and be influenced by it while at the same time developing their craft at their own speed without the competition, hype, or pressure that rappers in other parts of the city might have felt,” S.H. Fernando, Jr., author of the 2021 book From the Streets of Shaolin: The Wu-Tang Saga, told me.

Wu-Tang stirred its own buzz by working their records on college radio, touring historically black colleges, and building a critical mass of die-hard fans who soaked up the music as fast as the group could produce it. Their fans and the group united under the Wu-Tang “W,” which became a symbol of a hip-hop insurgency. Those same fans bought into the group’s comic-book-like origin story: Wu-Tang transformed their homebase of Staten Island into a place they called Shaolin, an invention drawn from equal parts real life in Black and Latino working-class sections of the borough—Park Hill and Stapleton–and the Shaolin of the Shaw Brothers martial-arts movies shown in the old theaters of the pre-Disney Times Square. The nine-man crew of rappers from Staten Island and Brooklyn, told stories of despair laid over soul samples from The Emotions, The Charmels and Dave Porter.

Related: The 6 Most Inappropriate = Wu-Tang Clan Names For Your Baby, Ranked

Wu Tang’s rise came during the crack era. Their drug-dealer-themed rhymes at times felt autobiographical, and their ties to the local drug trade were not lost on the cops in Staten Island. “When they saw us become successful, pulling up in front of the projects in limos to take our friends to rap shows, the cops didn’t like that,” Grant told me. “So they just sat there and watched us.”

More than 30 years later, the logo, which singularly encapsulated the band, its sound, and the world from which the music came, had returned home. The Wu-Tang “W” on the basketball-court blacktop was both a tribute to a time and place in the housing project's history and an attempt at branding. Grant paused over it for a second and then walked along the asphalt pathways, which were so wide the cops used to roll their cars through for drug raids. A steady cascade of snowflakes fell from the sky. Some got caught in Grant’s short, black hair, which bends in deep waves like the sea rolling in a storm. His face looked pained as he stopped at a spot just outside the court, about 100 feet from the logo.

“That’s where they said the guy dropped the hat,” Grant said, pausing at the same spot.

A green baseball hat emblazoned with the black flag and the Wu-Tang logo in the upper right-hand corner became the critical link between Grant Williams and the murder of a local drug dealer named Shdell Lewis on April 5, 1996. Flying off the head of the suspect that evening, the wing-like W of the Wu-Tang symbol tumbling to the pavement, it was a random castoff in the cacophony of pounding feet, quick deep breaths, and shouts following the murder, but it helped seal Grant’s fate and send him to prison for more than two decades for a murder he didn’t commit.

The trial of the People of the State of New York v. Grant Williams—a case that was thin on motive, plagued by conflicting eyewitness testimony, and not thoroughly investigated—played out over the course of two weeks in November 1997, but the forces had been building for decades. Poverty, a drug war, a gun war, and racialized politics created the conditions that made it easy to incarcerate someone with Grant’s background, robbing him of the chance to tell his story the way his friends did.

“I was accused of this murder,” Grant said. “That right there ruined any type of career I even thought about having because they incarcerated me unjustly

Click here to read the full story.

Truly*Adventurous crafts mind-boggling true stories and reported narratives, across a wide range of genres and topics. Their digital magazine can be found here.