Illustration: Moya Garrison-Msingwana

I’m 34 years old. It’s a weird age, teetering between being in touch and stuck in my ways. And I know I’m not the only one standing at the intersection of Young Buck and Old Head. Every time something comes along, whether it’s slang or pop culture or a new tech platform, you confront the same question: Am I too old for this? That’s why I’m here — to work through these conundrums on your behalf, on a weekly basis. Together, hopefully, we can face some harsh truths about our own washed-ness.

I’m sure you already know this now that we’re four episodes deep, but every Sunday night for the next month or so will be like church, the NBA Finals, Roots, and a trip to the barbershop all rolled into one. That’s because ESPN’s The Last Dance has landed early — one of the few positives to come out of the pandemic — and the docuseries about Michael Jordan’s ’90s-era Chicago Bulls dynasty is the content we desperately need. The show is the perfect blend of nostalgia, badassery, hero worship, and cursing. But, as is the case with everything in sports, it’s also ripe for debate. In particular, the show has become a reason for NBA fans (and, really, Michael Jordan and LeBron James fans) to relitigate the argument of the greatest basketball players of all time.

First of all, that’s absolutely the corniest possible way to watch the documentary. Ten hours of incredible content filmed over the course of the 1997–98 season, and you use it to look for ways to tear down legends? Second, it’s virtually impossible to measure sports across eras. The athletes are different. The nature of the game is different. The length of the shorts is different. But that won’t stop the people who lived through the Jordan era from proclaiming that the time they loved the most is the greatest ever and nothing can compare.

Those people are insufferable.

We all understand how nostalgia works, how there’s a natural human instinct to love the things from our formative years more than anything that comes after. But if I may offer a counterpoint: That’s a depressing way to live.

I’m sure you’ve known someone who refuses to acknowledge anything as great if it came after they graduated high school. They don’t think the NBA was any good after Jordan retired. They don’t think there’s been a rapper worth anything since The Blueprint came out. Every new artist is trash. Every great basketball player is soft. Clothes are too tight these days. Sneakers are too complex—“Whatever happened to Air Force 1s?” they might say. X-Men hasn’t been good since the Dark Phoenix saga. Thundercats was the last great cartoon. And NBA Live 95 was the best basketball game ever made.

We all understand how nostalgia works, how there’s a natural human instinct to love the things from our formative years more than anything that comes after. But if I may offer a counterpoint: That’s a depressing way to live.

Imagine living like that. Imagine cutting yourself off from a universe of great experiences out of a refusal to see the beauty of what’s new.

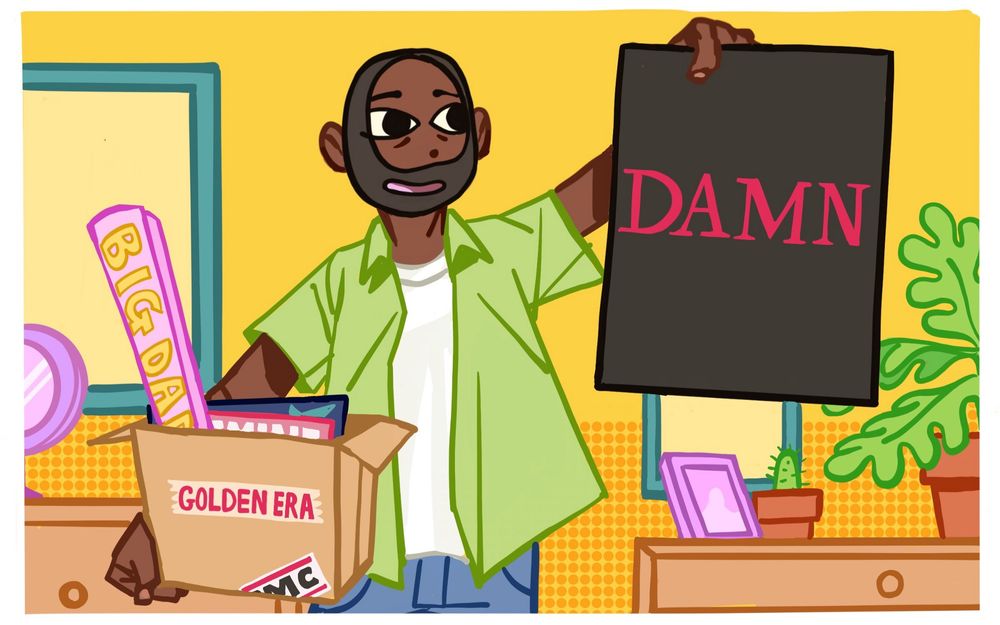

For instance, let’s take Kendrick Lamar. Good Kid, M.A.A.D City might be the best album of the past decade. To Pimp a Butterfly won a Pulitzer. Damn is damn near flawless. Kendrick has been the best bar-for-bar rapper in the world for years. But when I mention him to my peers as someone who might go down as an all-time great, they immediately scoff: “He’s no Jay. He’s no KRS. He’s no Rakim.” Are we sure? What exactly makes Kendrick Lamar immediately dismissed as someone who can hold up to those legends?

I get the same reaction when I say that the 2016–17 Golden State Warriors might be the best basketball team ever assembled. Where’s the argument? They won 16 out of 17 playoff games and ended the season winning 31 of the final 33 games. They had two MVPs, a defensive player of the year, and one of the best defenders of all time. But people like to fight back with teams from the ’80s that looked like they were on their way to an All Lives Matter rally. There isn’t a substitute-teacher-in-the-face-ass jump shooter in the world who would know what to do with Kevin Durant. And the entire league’s head would explode if Steph Curry showed up in the ’90s pulling up from 35 feet. I’d even argue that the 2010s was the best decade of basketball we’ve ever seen. But if an era pops up that’s better in 10 years, I hope that I can acknowledge its greatness and superiority.

The thing I don’t get about these nostalgia purists, these “Golden Era Warriors,” is their resistance to the joy of watching greatness unfold before our eyes. I love Jordan and the Bulls as much as anyone, but imagine how great the NBA would be if we had enough great players that #23 wouldn’t even crack the top 10 anymore. Think about the level of play we’d have every night.

Imagine if albums as good as Ready to Die or Illmatic popped up every month. That sounds like musical nirvana.

What it’s really all about is taking ownership of greatness — wanting to feel like the thing we loved is ours and ours alone. Not only is that selfish, but it’s tamping enjoyment under the guise of loving something. But this isn’t what love even looks like.

So here’s what you can do instead as a real grown-ass person. Love the things that you loved when you were growing up. But love them enough to know that they set the groundwork for the greatness you’re witnessing now. What’s more important than how we love the past is how we love the people around us — especially those coming along behind us, seeing our footprints. A little bit of “in my day” mock-bitterness is fun, no question, but once you take that past good-natured banter and toward “I’m dying on this hill” territory, all you’re doing is diminishing the things they hold dear and the memories that will shape them. It’s simple: Loving people means accepting what they love. All you have to do is get over yourself.

…Witcha hatin’ ass.