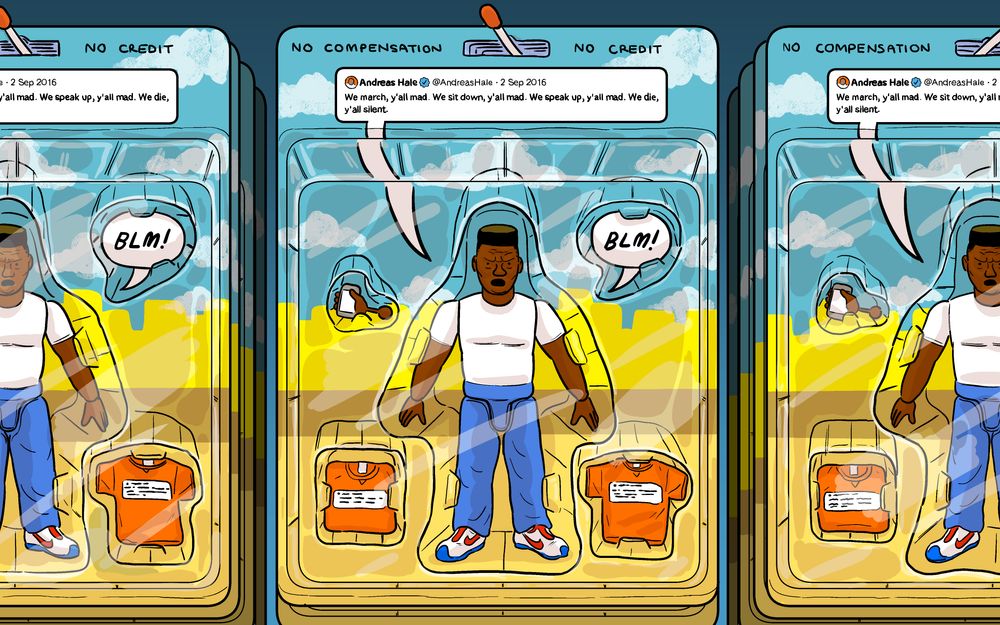

The revolution will not be televised, but it damn sure will be commodified in a country with capitalism as its economic backbone. Especially if it ends up in the palms of those who aim to turn Black pain into profit.

I’m not arrogant enough to suggest that my tweet on September 2, 2016, sparked some kind of uprising. But I do know there are disingenuous people out there who will shamelessly steal your words and try to become the official outfitter of nationwide protests for financial gain. I’ve seen it first-hand.

Imagine what it’s like to watch something you came up with being sold without your permission. There are no misunderstandings or misconstruing. It is, quite literally, word-for-word thievery. And not one or two words. Eighteen words. Four commas. Four periods. You’ve likely come across them one way or another.

We march, y'all mad. We sit down, y'all mad. We speak up, y'all mad. We die, y'all silent.

— Andreas Hale (@AndreasHale) September 2, 2016

Imagine being a comedian and someone takes your joke. But the comic doesn’t just borrow the concept and make slight alterations before presenting it to his or her audience in an attempt to claim it as their own. They lift it verbatim. Same cadence. Same punchline. Since that comedian is more famous than you, the joke reaches more people.

At first, you may be flattered. But then the joke becomes that comedian’s joke. And that comedian’s joke is now being told all around you by people who are oblivious to the fact that it was your joke.

“Remember that time [insert comedian here] said [insert your joke here]? I love that joke.”

Here you are, listening to your own joke. Only, it’s not yours anymore. It’s theirs. Maybe it’s funnier because of who is saying it now. Maybe not. One thing is for sure, you received nothing for it.

You’d be pretty pissed off about it, right?

But this wasn’t a joke or just an idea. There was an emotional attachment to these words that resonated with many people due to heightened racial tension in America.

You’ve seen the words on social media, on signs at protests, on cheaply made T-shirts, coffee mugs, tote bags, even a damn apron. Take a look, they’re in a book. Really. Check out the Google results. It’s impressive how far those words made it.

But do you know what you don’t see? Where the words came from.

People are profiting from my words.

And it sucks.

The genesis of my “y’all mad” tweet came from watching conservative America stew in anger over Colin Kaepernick’s NFL pregame practice of taking a knee while the national anthem played. Of course his silent protesting was in response to the rampant police shootings that had claimed the lives of Alton Sterling and Philando Castile—two Black men whose horrifying final moments were shared endlessly via social media.

The uproar reached a boiling point. Kaepernick had enough. So he decided to take a stand. Or rather, to take a knee.

Conservative pundits speaking on outlets like Fox News lambasted the quarterback for his choice of non-violent protest. I found it interesting that all these lily-white voices bubbled to the surface to criticize how we choose to peacefully protest but were conspicuously quiet regarding the root of the problem: innocent Black people dying at the hands of law enforcement. The apathy was appalling.

Common sense suggests we wouldn’t need to protest without a cause. Yet when we march, racists insist on telling us the appropriate (i.e. respectable) way to do so. During the Civil Rights Era, when demonstrators would perform sit-ins after being denied service due to the color of their skin, they were harassed and arrested for trespassing, disorderly conduct, and disturbing the peace. These days, when we speak out on racism in America, trolls call us race-baiting troublemakers who are stirring a pot for something that doesn’t exist.

But when our bodies are riddled with bullet holes and we’re laying in pools of our own blood courtesy of those sworn to protect us, that’s when they have nothing to say?

I was fed the hell up.

I didn’t consider who would like the “y’all mad” tweet or if it would have any major impact. After all, I’m a writer; I spend much of my day on syntax. Twitter is often my sounding board where I can express myself without an editor.

But then it took off:

We march, y'all mad. We sit down, y'all mad. We speak up, y'all mad. We die, y'all silent.

The likes and retweets began racking up quickly. Peers, people with large social media followings, celebrities—all were interacting with my tweet, keeping it circulating on feeds before I could get a grasp on what was happening.

At first, I was flattered that something I tweeted reached so many people. But like the game of Telephone, with every share, the message remains but the messenger—in this case, me—dissolves. Especially once I began to see people copy and paste my tweet—18 words, four commas, four periods—and repost as if it was original. And those tweets began to get more engagement than mine.

Still, I figured it was no big deal. Honestly, as long as the message resonated with people, I was fine with it. Ideas are meant to be shared, after all. But things changed once that tweet became intellectual property that was being used to line other people’s pockets.

I became annoyed and weighed down by complicated emotions. My intent was never to commodify the revolution. Yet others were doing exactly that—and making big bucks in the process.

I balked when I saw an online shop selling hoodies adorned with my tweet’s exact phrasing.

And then I began to receive text messages from friends who saw my words being sold on Gilden tees in random corners throughout the 50 states. They sent me pictures of these shirts.

And people were buying them.

I’d turn on the TV and see protests with people wearing those words or carrying signs with them written across. They had become a rallying cry. And one of the most ubiquitous items of the uprising.

A full year after I tapped that blue tweet button, images of LeBron and Kaepernick surfaced with my words photoshopped onto their T-shirts. People praised them for sporting a piece of clothing with such a bold statement. Unfortunately, they never wore such apparel. But that only made the shirts more coveted and the words more omnipresent—original author unidentified.

I became annoyed and weighed down by complicated emotions. My intent was never to commodify the revolution. Yet others were doing exactly that—and making big bucks in the process. They never thought to ask for my permission. They aren’t splitting the proceeds with a charity that’s in need. The money isn’t going to the NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund or Color of Change. Just the Shopify accounts of those looking to capitalize on what was hot.

I reached out to several of these online stores selling my words. I didn’t necessarily seek them out. My friends would send me links to virtual shops that were peddling someone else’s words.

I remember one interaction especially. I didn’t ask for money; I asked for credit.

And you know what they did?

They blocked me.

In 2018, I decided enough was enough. I had some shirts of my own made with my since-viral tweet and sent them to people I knew. Lena Waithe wore one for a Vanity Fair shoot—no Photoshop necessary. The aim was to try to reel the tweet back in and donate the proceeds to various charities. But I would need to sell enough to offset the cost.

Unfortunately, I was too late.

The capitalists capitalized and I was tardy for the party. And without an active racial conflict, the general public didn’t necessarily feel the need for those words. Things had somewhat gone back to normal. Because what’s activism without something active, right?

I say that in jest…kinda.

As expected, the topic had died down with the massive. Activism in the mainstream tends to fizzle out when the shell casings of the bullets that violated Black bodies are no longer hot. True activists are proactive rather than reactive. They fight 24/7/365. They don’t need to see blood on the leaves for their activism to heighten. But I digress.

Some time had passed with no real incident that sent us back out into the streets. The sitting president openly advocated and fully embraced racist, xenophobic, and misogynistic rhetoric to empower his voting base. That was bad. But it was our new normal.

And then February 23, 2020 happened.

The fuse was lit when a group of White men cut Ahmad Arbery’s life short for no good reason other than jogging while Black in Glynn County, Georgia. We wouldn’t see the video until May 5.

And then March 13, 2020 happened.

The wick burned when Breonna Taylor was torn down by an unnecessary hail of bullets that were a byproduct of an equally unnecessary no-knock warrant executed by plainclothes officers in Louisville, Kentucky.

And then May 25, 2020 happened.

The powder keg exploded when the Covid pandemic forced the world to witness Derek Chauvin nonchalantly put a knee to George Floyd’s neck for 9 minutes and 29 seconds. Or, until his life expired. All this brutalism over a counterfeit $20 bill.

This seemed bigger than the last time because we were all connected through our devices. It felt as if our eyes were being held open so we could watch the world burn. We had no jobs to go to, friends to see, travel destinations to escape to. We were locked down. The 21-year-olds who were still in high school when Kaepernick first took a knee had now found their purpose.

This was the time to put it into action. We spilled back into the streets in protest.

And then my words were everywhere all over again: tees, tanks, flags, face masks, onesies, stickers, pins, throw pillows, hats, phone cases. Virtual stores and Etsy accounts had popped back up in an effort to cash out with revolution merch. The plagiarized tweets were back, too. This time, there was so much distance from the initial tweet that my name had almost been completely detached.

My timeline was flooded with people pointing out the egregious heists. I appreciated everyone who reached out but I also stopped caring as much.

Without social media, my words would not have traveled as far. But because of it, someone else can benefit from something they didn’t have a hand in creating.

Some have asked why I didn’t copyright my tweet—all 18 words, four commas, and four periods—ahead of time. Imagine that. What kind of pretentious douchebag would I have to be to file a copyright in advance for a tweet I think is going to resonate with the masses? Also, that’s not Twitter’s purpose. It’s often an emotional outpouring at the spur of the moment. I didn’t conceive that tweet for weeks in advance and schedule it to go live. I typed what I felt when I felt it.

Twitter’s Terms of Service outlines instances such as mine. They protect users from having tweets appropriated. But the area is still very gray. The Copyright Alliance laid it out as simply as “if you come across a particularly catchy tweet, it’s probably not the best idea to turn that tweet into a t-shirt line without permission.”

It just felt like far too much trouble, time, and effort to obsess over. I had other things to do rather than send cease-and-desist letters to online merchants. That train had left the station.

However, a similar issue made the news in 2017, when a shirt worn by Frank Ocean at New York’s Panorama Festival became a viral sensation, only for folks to realize the online merchant who made the shirt had lifted it without permission from a student’s 2015 tweet.

The two sides eventually came to a compromise. That’s cool, I guess.

What do I want? Credit would be nice. But if you decide to shamelessly turn a profit off someone else’s words, perhaps ask for permission. Or, you know, offer them a cut. Even better, donate the profits to the cause those words support.

But, really, I want what most people want: acknowledgment.

It’s the gift and curse of social media. Without it, my words would not have traveled as far. But because of it, someone else can benefit from something they didn’t have a hand in creating.

Maybe this column will spark something within someone to make a change and protect the little people from having their words stolen for profit.

Maybe not.

For those who’ve made money slinging poorly designed T-shirts with my words on them or gained followers by using my words to go viral, congratulations. You did it. And you’ll probably do it again.

I purposefully opened this op-ed with words largely attributed to the legendary Gil Scott-Heron, whose poem and song "The Revolution Will Not Be Televised" was released in 1971. Those words still ring true to this day. And many people don't credit him for it.

Did he come up with it first? It doesn't really matter, does it? Because those words will live forever, no matter where they came from or who profited most.

Like it or not, that’s the American way.