Prior to its release, Nas’ 2002 compilation album The Lost Tapes—intended to collect and repurpose bootlegged gems that had been circulating on the mixtape circuit—was bootlegged itself. That’s how rabid the demand for Nas music was at the turn of the century.

The 12-song project, which was the brainchild of the Queensbridge rapper’s then-label Columbia Records, culled together stellar outtakes from I Am, Nastradamus, and Stillmatic, hitting a sweet spot that recalls Nasty Nas-era brilliance and delivers on its tagline’s promise: “No cameos, no hype, no bullshit.”

These former throwaways were the furthest things from trash, collectively on par with Nas’ most extolled LPs. Despite a deliberately laissez faire approach by Columbia, The Lost Tapes debuted at No. 10 on the Billboard 200 and, more importantly, gained its own legacy—Rolling Stone dubbed it “the real Stillmatic” back in ’02, drawing a direct lineage to Nas’ debut masterpiece, Illmatic.

The Lost Tapes rewrote the rules for hip-hop back catalog releases and redefined their upper limits. Without this example, it’s unlikely that years later folks like Kendrick Lamar and Drake would’ve dropped their own delicious batches of leftovers, untitled, unmastered and Care Package, respectively. (Ditto for Nas' own The Lost Tapes 2, which, upon its 2019 release, was not as warmly received as its predecessor.)

As The Lost Tapes marks its 20th anniversary today, LEVEL revises archival interviews from 2017 to present a comprehensive look back on the project’s conception, from its storied recording sessions, to the rampant leaks that inspired its concept, to its place in Nas’ legacy.

LOST AND FOUND: THE PLAYERS

Al West: Co-producer of “Drunk By Myself”

Deric “D-Dot” Angelettie: Co-producer of “Poppa Was a Playa”

David Belgrave: Product manager of The Lost Tapes

DJ Doo Wop: Prominent New York City-based mixtape DJ

Julian Alexander: Art director of The Lost Tapes

L.E.S.: Producer of “U Gotta Love It” and “Nothing Lasts Forever”; co-producer of “Blaze a 50”

Larry “Precision” Gates: Co-producer of “Doo Rags”

Lenny “Linen” Nicholson: VP of A&R of The Lost Tapes

Michelle Bell: Co-producer of “Doo Rags”

Nas: God MC (interviewed in 2003, shortly after The Lost Tapes‘ release*, and in 2017)

Poke of The Trackmasters: Co-producer of “Fetus,” Drunk By Myself,” and “Blaze a 50”

Rockwilder: Producer of “Everybody’s Crazy”

—

Lenny “Linen” Nicholson: I was involved with Nas, Trackmasters, and Steve Stoute from It Was Written. I was always around in the studio so I knew all the records that never made the albums, which were some of my favorites. At the time I was recording Stillmatic with Nas, Columbia Records wanted to create catalog, knowing that we were spending millions of dollars in recording budget and trying to see if we had anything commercially viable that we could put in the marketplace that could compete with something the artist would deem his official album. Me and David Belgrave came up with the title, The Lost Tapes.

David Belgrave: We didn’t put out any single or video. We didn’t have a typical radio plan. We didn’t even do a packaging photoshoot with Nas. We just leaned hard on the press and the strength of the records—the records were just so hot. It fit how he was surging during that whole period from “Oochie Wally” into Stillmatic and God’s Son.

Nas: I wanted [my third album] to be a double album. I just seen the way things was goin’. It was moving into that: Tupac, Wu-Tang Clan, B.I.G. I was right there, the next one to get that one out there. That turned out to be I Am…. Songs like “Project Windows” had leaked already, and other records was out there. That killed the whole double album thing.

I had so many songs lying around that are weird that I wouldn’t want anybody to hear—I [was] embarrassed. —Nas (2003)

Julian Alexander: I knew bootlegging influenced where this album came from—it’s basically bootlegged songs and B-sides. To this day I have a shoebox where I keep things that are really close to me, like my private stash. My thinking was, “What if these were not in a big vault, but just like a little stash box where [Nas] kept things that were important to him?”

The photographer is a good friend of mine, Kareem Black. We started collecting things. We went to over by Vernon Ave., by the edge of Queensbridge Park, and found a little spot in the cut. We dug a hole and stuck this box in there. On the album cover, that’s my passport, a mic that I had at my house (it’s just a prop), a couple ones with a $100 bill wrapped around. So we shot this and that’s where the imagery came from. And Kareem shot some pictures of the bridge, of course. I’d done another version of the album cover but I ended up passing this one off to [art director] Chris Feldmann. Chris kinda kept those elements and did his own thing. But the photoshoot, initial design and handwriting on the cover is all me.

+

Poke of Trackmasters: We recorded a lot of records at one time, back to back. Nas didn’t even want these records to come out. All of these records were at The Hit Factory and they started leaking. It was like 40 records, just out there. Sometimes A&Rs would have a DAT tape in their office, next thing you know that shit wanders and fucking [Funkmaster] Flex is blasting off to it. [DJ] Clue and fucking [DJ] Doo Wop had the shit on their mixtapes. It was getting out of control so we had to capitalize on the fact that it was out there and niggas was feeling that shit.

DJ Doo Wop: In the street, people were fiending for that new Nas. All of the DJs was trying to get the shit. There was definitely a big anticipation.

Nas: Usually I work on songs just to get a feel for being back in the studio. And still, songs would leak. Or they would be put to the side, ’cause they wouldn’t be what I wanted on the final cut. Then we’d release the album and we had unfinished records: A verse on a beat, three verses on a beat with no chorus, one long verse on a beat. Whatever it was, we had no home for ’em. Nothing to do with ’em. They’re not records that I wanted on an album, just stuff that we had. So, you know, we started to think about Lost Tapes.

Sometimes A&Rs would have a DAT tape in their office, next thing you know that s--t wanders and f--king [Funkmaster] Flex is blasting off to it. It was getting out of control so we had to capitalize on the fact that it was out there. —Poke of Trackmasters

Al West: It was a few records of mine that were being leaked. At first I was upset because that affects royalties. But I wasn’t upset about gaining the credibility. I was just a young’un, probably like 20, around 1999, so I was honored. But at first, you don’t want your special work leaked for free. So of course your first reaction is going to be, “Yo, who the fuck did that?” A few other producers felt like that too. Like, “Why they leaking the hot joints?” But I got over it. People from the hood would come up to me, like, “Yo, that [“Drunk By Myself”] record is crazy.” And I’m like, “Wow, you heard it?” That made me feel good.

Nas*: I was never totally pissed off, because people was able to enjoy the songs. I was always happy about that.

Nicholson: Leaks were happening so heavily, especially for Nas. It was hard to prevent because if you have samples, they have to go out for clearance. I’d never release any song of his without throwing some obnoxious sound through it. I put a dog barking throughout a song called “Death of Escobar” and sent that out for sample clearance. It leaked, so I knew where it came from. A lot of times we released the records ourselves though, to create a buzz and feed the base because Nas usually took a bit of time between projects.

Belgrave: I know the whole paradigm has changed, but when you think about how Drake releases records—like, bam, bam—that’s basically what was happening for Nas during this phase and it was all fucking great.

Nicholson: I discussed the Lost Tapes idea with Nas and he loved it. As long as he could put it together in a sequence the way he’d do his normal albums, it would be great. I don’t think that it mattered what was out before, because you receive it differently when you have a body of work. That’s why we didn’t release a single. We didn’t want to piecemeal it, we wanted them to absorb the full project. This was something that Nas was very adamant about.

Nas*: I wanted people to hear ’em in the proper way. I had so many songs lying around that are weird that I wouldn’t want anybody to hear—I [was] embarrassed.

+

Poke: Nas was real meticulous with his writing. He would change a verse three or four times—he did that with “If I Ruled The World.” There were joints where he would put down a verse and we didn’t use it. So we would take some of those verses and maybe add a new track and put it on Lost Tapes. Or he might revisit a changed verse and use it for that. We rounded up songs that we had from It Was Written and I Am and decided that we were going to add additional records.

Nicholson: I went in and started going through tons of records, whether I had a verse or full song, and started to piece it together. I was pulling two-inch reels from the studio and seeing if there was something I needed to update. This was strictly my favorites. If it was something that I loved but it was unfinished, I’d ask Nas about it, and he’ll yay or nay it. If it was a true favorite of mine, I’d try to convince him, but it’d have to be his vision, otherwise I’d be doing him an injustice.

Poke: There wasn’t an overall theme because the records are in different places. Sonically, we were trying to make it feel like somebody broke into the vault and just took a lot of masters. We was trying to make it real grimy, real dirty, like something that wasn’t supposed to be released.

When you think about how Drake releases records—like, bam, bam—that’s basically what was happening for Nas during this phase and it was all f--king great. —David Belgrave

Doo Wop: What was dope about [The Lost Tapes] was it sounded like a mixtape. A dope rapper over raw beats. I love songs with singers and all that, but he was just free on that joint. Even the Barry White sample to “No Idea’s Original”—all those joints were raw. Some of them did leak maybe without a third verse, so when the official joint came out, you was getting a little bit of extra shit.

Nas: Mixtape DJs was all about exclusives. So that just fit perfect for what they was doin’.

Nicholson: The point I always like to make when sequencing (especially a Nas album) is keeping it consistent, so you can ride out to it. If you love the first two songs, you’re going to love the first seven. I like to keep you in the mood. I just heard “Doo Rags” setting everything off.

Nas*: When I do shit like “Doo Rags” and “Black Zombies,” that’s the music that I like to make and just play for myself. Everything ain’t gangster shit. It’s just cool shit. I love music.

Michelle Bell: Larry Gates was one of the few producers that would listen to my piano ideas and rough sketches. He and I were working on Britney Spears at the time. I took something over to his house and played the piano for him—I think I was playing it like whole notes, holding the chord. He did that run in the middle of each chord and he was like, “This is so pretty.” I was a terrible piano player, so he replayed what I put together. Typically I’d have melodies or chord ideas and then he would build a drum track.

Larry “Precision” Gates: Michelle sat down at the Wurlitzer piano and started to pluck out a few different notes. She was playing something that was in the vein of Stevie Wonder’s [“Blame It On The Sun”] and “Greatest Sex I Ever Had” by R. Kelly. As soon as I put my hands on it based on what she was doing, I came up with the piano riff. There was no instrumental made that day, I just took mental note of what me and her did.

Bell: I had a verse, melody, and I think a chorus. The song wasn’t that great, but that piano loop was pretty special though. I had a feeling that as soon as he got in the room with Nas, the first thing he was going to play was that loop.

Precision: Corey Rooney and L.E.S. were involved in me coming to the studio. I played four or five instrumentals for Nas; there was no real reaction. I was nervous that I wasn’t going to make the cut. I went to the piano room and started to play that piano riff that me and Michelle made up. Then I started messing around on the MPC3000, brought up a drum beat, started messing around with the nylon guitar to make the hi-hat pattern. From there, L.E.S. had a few ideas, but Nas looked over and said, “Ah man, just let him go.” It was about a 20-minute ordeal. Nas sat down and wrote all three verses right in front of my face. The instrumental [for Stillmatic’s] “Smokin’” was also made in that session. I believe the Wurlitzer sample is the same for both songs.

Nicholson: Precision is one of the few new guys that was able to be in the studio with Nas. It has a lot to do with who his dad is—he’s Roger Troutman’s son—and also me explaining what his musical talent was. Nas just liked the energy.

Precision: I couldn’t understand how he was able to be so rhythmic using so many words, so many syllables, but he just kept everything so in time. He knew exactly what he wanted to say, how he wanted to say it. He knew how to deliver a feeling that was correct for the track. I guess that’s what a real MC does. I think he did the whole thing in one take, and the third verse he ended up punching twice.

Nas*: Living in Queens, you’d see it on different streets en route from the courthouse to the island—they’re still bussing out American youth into the prison system, no matter what. [Like a school bus], except it’s a jail bus. Back and forth. It makes you think, like, “What’s happening?”

Bell: They kind of jacked the track, but it was still awesome. I never fought it, I was like, “Who doesn’t want a Nas song?” Back then it was kind of unheard of to have a female producer on a song, outside of Missy [Elliott]. Larry and I talk about it now and he’s like, “You totally deserve production.” But Nas has always been really gracious about it and we’ve laughed and talked about it a few times. I got tons of street cred from that song, so I’m super proud of that.

Precision: When it was time to do the final mix of that record, the piano part—one of the song’s hallmarks—got corrupted from the Pro Tools file. I ended up having to replay that piano part. So that was not the original piano with the feeling from that same session, which was amazing. There was only four people that heard that original.

Nicholson: “Doo Rags,” “Purple,” “Everybody’s Crazy,” “Black Zombie”—those were essentially newer records. They had to be consistent with the songs that were done during the previous albums, feel like a song he would’ve written back then.

+

Nas*: My thing on “Black Zombies” was: Black men, find your identity. Who are we? What makes me fucked up is when Black motherfuckers bleaching they skin to the point where it destroys their skin. I understand it. I think it’s mental poison to be ashamed of your blackness. But it’s no different than white people or Japanese people tanning. Do whatever you wish with your body. It’s a shame if you hate yourself.

Nicholson: “Everybody’s Crazy” was originally for Stillmatic. Rockwilder came up with some incredible stuff. It just fit.

Rockwilder: That’s one of my favorite tracks that I’ve ever done. It was one of those fresh joints. Me and Nas was in the studio and as soon as I did it, he jumped on it. He loved the beat. Back then when you had to lay a track to reel you had to use a SMPTE code. I was using an MPC3000 at the time—the MPC3000 is weird. When you play a beat, it has a play/start method where you can start and stop it yourself. I told the engineer I don’t want SMPTE, I wanna start and stop the track myself, so it had that live feel. And also there was no samples on that. That was me playing the track.

Nas: I love that track. That shit’s hard. I remember writing that song over and over and over for months and months. I couldn’t kill it like I wanted to ’cause the beat was challenging and the beat was hard. I loved the beat so much I was trying to get the perfect words to it. I spent a lot of time on that.

My thing on “Black Zombies” was: Black men, find your identity. Who are we? ... I think it’s mental poison to be ashamed of your blackness. —Nas (2003)

Nicholson: I remember Hill Inc. did a record for me where Nas went at Puff [“Purple”]. Puff didn’t like that record. Puff called and they spoke, and then that was that. It was a simple conversation. Puff understood he’s a writer [and] that’s what they do.

L.E.S.: We was in Miami when we did “U Gotta Love It.” It might’ve been around the time we was doing It Was Written or right after. I was just fucking around with the sample. I looped it and realized that it was three bars and I was like, “Ain’t nothing you can do with this.” That shit was really like an accident. I played it for him and he was just like, “Whoa, this is dope.” Nobody would ever rhyme on a three-bar turnaround loop—they didn’t know how to. Nas was like, “I’ma do this shit.” He wrote to the beat right there. I had an AZ sample on one of the pads and was hitting it. This is what they want, huh. It came out classic.

Nicholson: A lot of times Nas would go in and freestyle what comes to his head. He’ll sit in there and record a song, but it could be off the top, just based off the energy he’s feeling. Then he may say, “Alright, we’ll keep this, we’ll trash that.” He’ll come back out the booth and finish writing.

Nas*: I freestyled [“My Way”] on my birthday in ’99. I’d carried the thoughts around.

+

Doo Wop: I got “My Way” and the rough version of “Project Windows” [from Nastradamus] in 1999, on the same CD or tape. “My Way” was that joint. It didn’t have a hook on it—it was just the three verses, but I was loving the flow. He was rhyming over the little bells and shit, the keyboard. His flow was right in pocket. Nas in raw form.

D-Dot: “Poppa Was a Playa” was made I guess ’98, ’99. This was my first time working with Nas. That was a Kanye [West] track. Kanye was extremely talented, good spirit and very humble when I met him. He wasn’t in the studio at the time for none of the records, because he didn’t live here—he was in Chicago. Back then, there wasn’t a lot of collaboration on music with Kanye in the initial stages. He would send me tracks and my job was to take the tracks to the next level by adding piano, chords, strings, extra drums, and sound effects. I went in and did whatever little overdubs that I needed to do, and helped Nas with the vocals, adding the hook and mixing. That was the beauty of the co-production. I’d go sell the beats, though sometimes [Kanye] didn’t even know what beats were being sold until after I sold them.

Nicholson: Kanye called me, like, “I did the track.” I was like, “Really? I had no clue.”

D-Dot: To be honest, The Lost Tapes album was a real thorn in my side because of what it did to Kanye. I think that spawned one of the “ghost producing” terms that he came up with. Because Lost Tapes wasn’t put out ’til years after we did it, they never called or e-mailed for credits. I get a phone call from Columbia telling me that the album would be out in a week. When the album came out, they’d just put my name on the record, which clearly wasn’t correct. But I had no control over it. I had to go back and ask them to change the credits and tell them they fucked up. I had to tell Kanye what the situation was and that got ugly because when you’re young and trying to come up and it’s Nas, you want your credits. It looks like D-Dot did some foul shit, but I was never on that with anybody.

Nicholson: It was totally left field for me, because it was one of my favorites, but Kanye was brand new on the scene. He was never in the studio. I had to make sure Kanye was taken care of.

D-Dot: Nas doesn’t need anybody’s help for lyrics. Once he gets direction, if he’s working with a real producer, then he’s off. Everything he came back with was from his mind. Conceptually, we just talked about various ways to have each song have a uniqueness to it, like, how to take subjects that don’t make the typical “I get money, I’m the best” braggadocio. Anything we did, I wanted to have not only standout beats, but standout concepts, lyrics, hooks and sounds. And that’s what he came back with.

+

Poke: Nas comes up with concepts that are food for thought. Imagine looking at a painting and you get a word or a concept that comes to you when you see it. Nas kinda writes that way. He would come up with a few words or a concept and start building from that. So he’ll say to us, “Yo, I got this idea for, like, being in my mom’s womb.” It’s unimaginable until he starts putting words in there and you’re like, “Oh my god.” Just like what he did with the gun record [“I Gave You Power” from It Was Written]. The way that he articulates is nuts. I always thought that he paints pictures with words.

Nicholson: “Fetus” was originally recorded for I Am. That was a very important record. It goes along with the themes that Nas has consistently had in his albums, about giving you the essence of something and taking you along on that journey. Every artist has that one thing. He’ll either take you from the end back to the beginning or from the beginning to the end.

Poke: It’s almost like doing a score to a movie, you basically gotta make something that matches the picture that they give you. We tried to keep it real simple, it wasn’t anything dramatic. We just used MPC60s and we had a Triton or Trinity—I can’t remember exactly which one. Find a hot loop, hot sample, throw it in there and just build around that. We tried to make the drum drive so it had some passion behind it. Sometimes when somebody had the concept, you really gotta listen to what the artist is saying and just stay out of the way. The lyrics was so intellectual, I was like, “Yo stay outta his way. He’s like a instrument, so let him do the lead.”

Nicholson: I had an issue with clearing a sample [on “Fetus”]. It just sat. Chucky Thompson actually had to replay that whole record for me in order for it to get done.

Poke: We were sampling these Latin records, so we weren’t clearing shit. We had to get some musicians in to play it and try to keep the feel of that sample, keep it as dirty as possible but still give it that thing. We had to do that a lot, especially with “Hate Me Now.”

Nicholson: “Fetus” was one of those songs where I was like, “Gosh, I wish people could hear this record.” Thank God I had the opportunity to put it out. “Drunk By Myself” was also from I Am, one of my favorites. As a producer, especially during that time, no one would’ve played that for Nas. Al West was a musician. He played something that resonated with him and it worked.

+

Nas: That one I like a lot, ’cause I put a lot into it. But sometimes you don’t want that… It doesn’t fit the rest of the records that you really want to put out there. So it’s just a record that you have, but don’t really want everybody to hear it.

West: I was just starting off in the industry working with Trackmasters. They were going upstate to Bearsville, [New York], to record a bunch of records with 50 Cent, Nas, I think Noreaga was up there. It was like a resort. One day Nas was like, “Let me hear your beats.” I put on [“Drunk By Myself”] and he was like, “Yo! I need that beat. This shit is crazy, wait ‘til [DJ] Premier hear this shit.” To me, it was like a storytelling beat. I automatically thought if anybody got on it, it’s great for a story. So we was just vibing. Everybody had hella drinks. There’s nothing like the spur of the moment type vibe, like, “Yo! Get in the booth right now.” He did the record right there, wrote it and had his Henny bottle in the booth. Tone and Poke came in and put the sound effects to the track. We all collabed together.

They was just in the studio high as f--k, [thinking] of the most ratchet s--t that could happen. They'd sit around and joke like, 'Yo, imagine n-ggas doing da-da-da' and he’s penning it. That’s how a lot of the ideas be coming. —Poke of Trackmasters

Poke: Sometimes when you get an idea for a record or a concept, you gotta make sure that you’re painting the proper picture. Sonically, in order to do that, you gotta change things or try to tailor it to give it that mood. That happened all the time where it may be a loop, kick, a snare, and some hi-hats. Next thing you know, it’s this big-ass orchestrated piece, but it still sounds grimy. But when you start pulling up tracks, you notice that there’s 30 tracks—that’s what it takes to make it sound like it sounds.

West: If you listen to the song, it’s like you’re riding through the streets. You had the gun, the Henny bottle making noise—motion picture shit. [Nas] made how I felt doing the beat come to life. Sometimes I’ll start reflecting and I’ll put that record on. He didn’t really talk specifics on the meanings. I guess that was how he was feeling that particular day. But you know, Nas is a poet, so he has a great way of putting scenarios into poetry.

Nicholson: When I was working with Nas, he just had his childhood friends with him, people from QB. [His younger brother] Jungle is absolutely instrumental in the vibe, the energy, and the stories. Another friend of Nas from the hood is Lord. [Song concepts and ideas] all stem from their conversations, their camaraderie, their friendship. When we started Stillmatic, it was just me, Nas, and Lord in the Bahamas for three weeks, working, catching a vibe, going through stories. They would often reminisce about a lot of situations. Getting him in a certain headspace was important. Nas reads tons of books, he’s extremely intelligent. He pulls from everything. If he read something poignant, I know what type of record I’m going to get. If I have Jungle, Wiz, and Lord in the studio and something aggressive comes on, I know what kind of record I’m going to get. He’s a living and breathing sponge.

Poke: There was a time where Nas was in the studio and we was just recording for no reason at all. That’s when he started coming up with all of these different concepts. “Blaze a 50,” [N.O.R.E.’s] “Body in the Trunk,” [“Fetus”]—all of those records were done in the same series of sessions. He was in the conceptual frame of mind at that time. They was just in the studio high as fuck, [thinking] of the most ratchet shit that could happen. They sit around and joke like, “Yo, imagine niggas doing da-da-da” and he’s penning it. That’s how a lot of the ideas be coming. “Blaze a 50,” we already had the track. That’s when the track is playing and everybody’s getting lye’d up, so the ideas start coming. That’s how that one came about. You put the track on loop and the pen just starts.

+

L.E.S.: I forgot which album they were working on, but they just needed some more street records and I just went into that Queensbridge dark belly. The muhfuckin’ drums were knockin’ on that bitch. He started rapping on [“Blaze a 50”] but he never finished the song. So he was like, fuck it, I’ma just leave it at one verse. Trackmasters was like, “We should make the beat rewind like this and slow the tape down,” different little shit like that. That’s how I learned to really produce. They knew everything to do. When Nas finished, it took me like a day to find a whole bunch of sound effects and match those to what he was talking about, because the song was so movie script written. It was like a soundtrack.

Rockwilder: You do tracks sometimes and you never know what kind of history is gonna come with it. But to be on Nas’ Lost Tapes is just incredible. He went into a zone.

Belgrave: People just wanted to hear him rhyme and he’s on this creative roll and everything was just right about it. That was a very special time.

Nicholson: To me it embodies everything that Nas introduced to us. Usually people become fans of your first album. I wanted to give you an extension of that growth with a consistent, coherent masterpiece. That’s why I feel it’s still beloved to this day. True Nas fans got a vibe that they were able to stay with consistently. They didn’t necessarily get that with every project until we did Stillmatic.

Poke: It was the no-holds-barred rhymes. It wasn’t for radio, it wasn’t commercialized, none of that. It was just Nas unchained. When Nas was on his bragging shit, niggas ain’t wanna hear that. I think that’s what the allure was. It was so grimy that people loved it. They kinda equated it to Illmatic in that sense, where the rhymes are just insane.

Nas*: I just do what I like. And I’m happy when people love it. I can make a living off of this. Already I made a living off this, so I can continue to make a living putting out songs that only a few people like.

Belgrave: I remember me, Nas, Lenny, and Chris were all in Miami doing the God’s Son album packaging shoot that Jonathan Mannion shot. Early that morning, the numbers came out—Lost Tapes debuted at No. 10 on the Hot 200. For not using all of those traditional means, we definitely got good press. It was just mad celebratory. “Made You Look” was already lurking up in the wings. We just steamrolled.

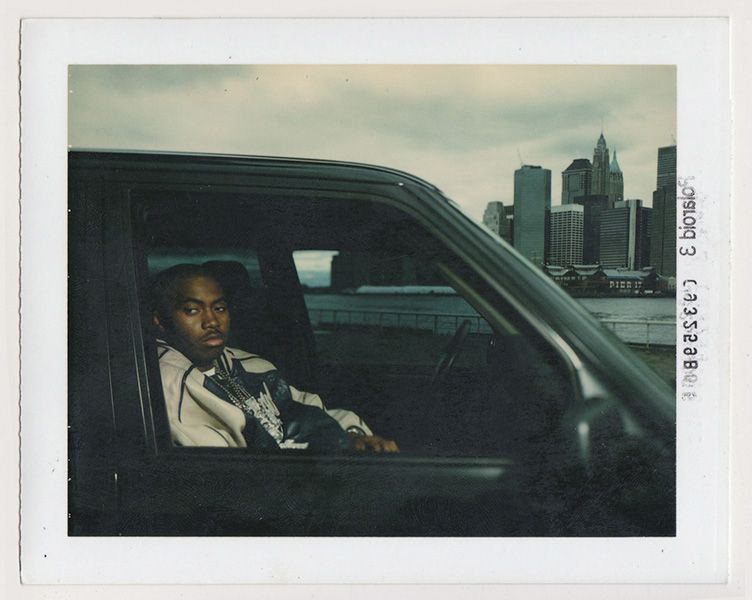

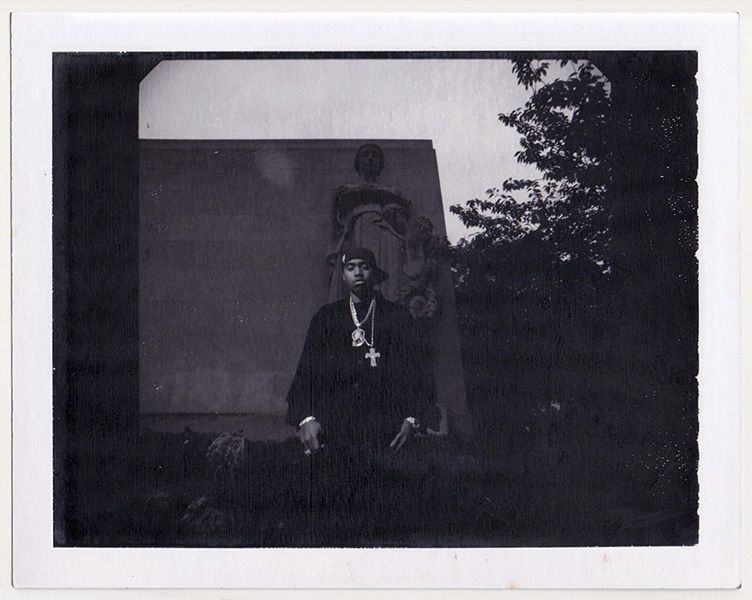

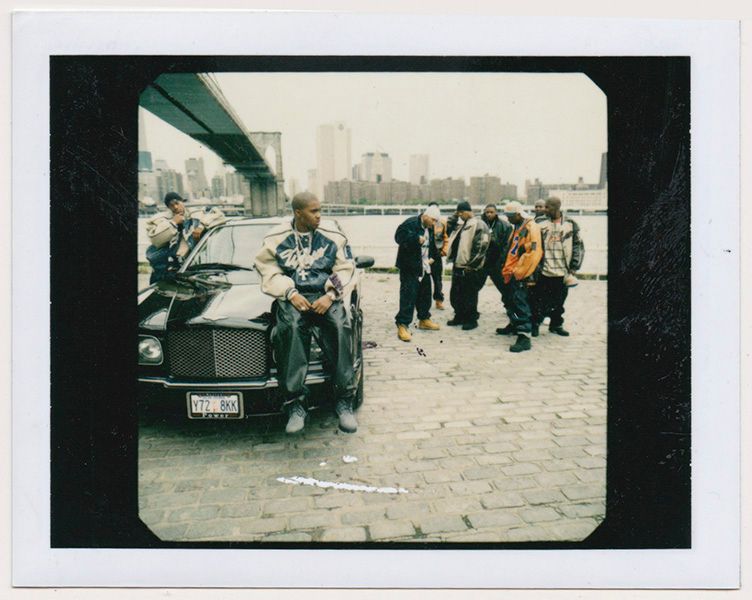

Special thanks to Julian Alexander for providing original polaroid images shot by Kwaku Alston. You can view more vintage photography in Julian’s portfolio.