The largest angels rarely live the longest. For centuries, intellects and clergymen from the Eastern Hemisphere have spoken on existence being dictated by purpose. It’s been said throughout a myriad of cultures that once a person has completed his or her education, as student and teacher, their time in human form expires. Wherever your spiritual philosophies lie, Earl “Dark Man X” Simmons being a gift not only to music, but, more importantly, to the society of music lovers should be universal comprehension. Yes, the present was DMX’s presence. Moreover, the gift was a sum of his God-given gifts. Aside from the Dog’s rare ability to go rhyme-for-rhyme with Jay-Z or single-handedly alchemize a flawed film into a hip-hop classic, his greatest contribution was deliverance.

X was a pastor in every sense; a vessel entrusted with a single celestial word that only his tongue could deliver. A gravel-voiced teacher and documentarian, he showed us the real — our beauty, our ugly, our faith. He warned: Never lose sight of your demons if you intend to escape their web. He articulated the best because he showed more than he told. Yet, he never allowed vanity to sully the mission. He has slipped and fallen in front of us. He showed us that it was easier for him to uplift the world than himself. Imagine the Greek titan Atlas in a wheelchair.

DMX injected totality and spirituality into a hip-hop scene that at the time was as inebriated as it was distracted. This was the back end of the 1990s. The first half saw reality rap raise hip-hop music’s bar via cinematic rhymes. Nas and Biggie and Prodigy and Raekwon lead the Big Apple-powered renaissance, giving listeners HD views of the cold benches of Queensbridge Housing Projects, bubbling prayers inside of Pyrex Vision pots, hustler’s regrets and suicidal thoughts, MPVs that were fat. By the decade’s midpoint, successful rap artists wanted an escape from the struggle. Hip-hop was growing along with the bank accounts of its stars. Sean Combs wanted to change the narrative, which was understandable — even plantation slaves got to sing and dance on Sundays. Thus Puffy instructed everyone to wave their first Rolex in the sky. While the images of Bentleys, platinum and diamond shimmers, and yacht rides atop turquoise waters were hip-hop accurate (for a minority few), they weren’t a complete picture of Black life of the era.

DMX knew that his innocence and right to choose was sacrificed in order for the world to better love its scars. His tragedy is your gift.

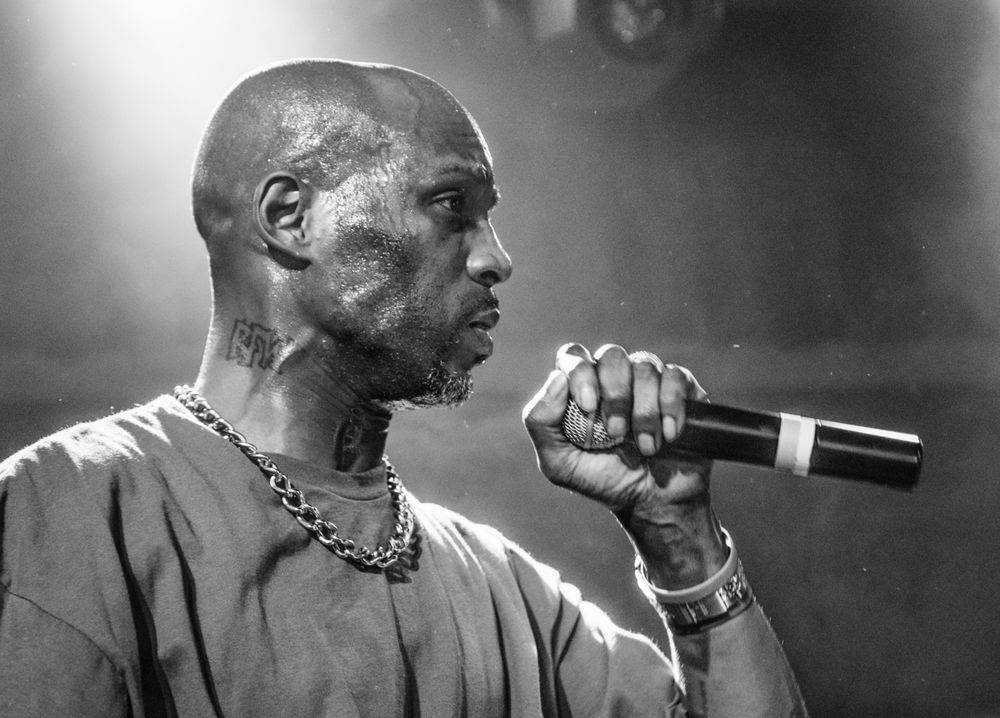

Enter a shirtless, hangry DMX in stark black and white. Physically — baldheaded, shirtless, tattooed, chiseled — he best represented the Black man of every prior decade. The dog chain he wore uniformly spoke to both oppression and liberation for himself as well as his people. Without uttering a syllable or growl, he recalled Shaka Zulu, or Denzel Washington’s Private Trip in the film Glory, or Levar Burton’s Kunta Kente in Roots. But DMX belonged to no one more than clean-headed, shirtless Tupac Shakur. It’s almost unfathomable to accept that Pac’s successor was more raw and more spiritual. They both single-handedly moved the world.

Pac passed in 1996. In 1997, African-Americans were still in a ravaged state due to racism and the crack era of the ’80s. Devastating legislation like the infamous Crime Bill of 1994 removed Black men from Black households, beheading many Black families. People of color arrested for marijuana offenses were receiving more jail time than some violent criminals. Life as a minority in America rarely came with Hype Williams’ fisheye lens. From Compton to N.O. to Yonkers, shit was still dark and hellish. DMX delivered a full reflection of the Black narrative by becoming the four-legged antithesis of the Shiny Suit Era. Diddy’s flashing lights showed the abundance and celebratory side of hip-hop’s moon, but X represented the cratered, shadowed flip side. Even crazier, he held this position while in a love/hate relationship with the moon.

Hip-hop was the conduit for DMX’s greatest demon. At the tender age of 14, he became the mentee of a local criminal who, like X, aspired to rap for a living. Young Earl Simmons had deep love deficiencies and abandonment issues. So the fact that his mentor praised his embryonic rap talent meant the world. Until his final day on Earth, he never understood why his mentor would pass him a blunt laced with crack cocaine. It’s enough to make any man hate the conduit. Nevertheless, X clutched his favorite three letters (G-O-D) and personal palindrome and persisted on. He never stopped leaning into his purpose, even when distracted. Even when fallen. DMX knew that his innocence and right to choose was sacrificed in order for the world to better love its scars. His tragedy is your gift. There’s no greater thug love.

Read more: DMX Is Finally Happy