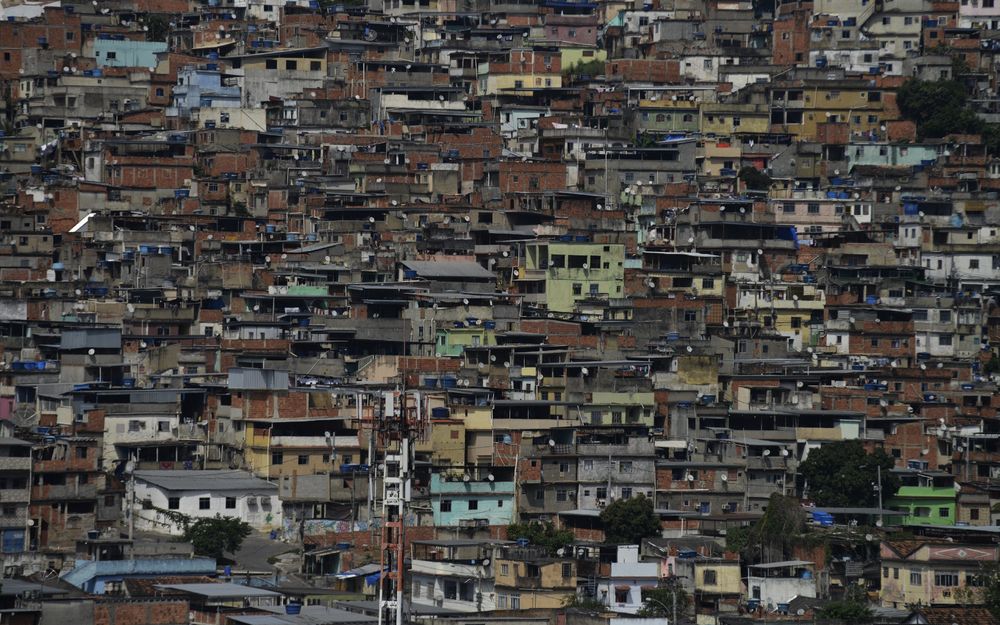

The favelas/56422/">majority of Brazil’s population is Black and mixed-race. That same population also makes up the majority of the country’s poorest and most excluded communities in the outskirts and favelas of major cities. Black and mixed-race Brazilians are 2.7 times more likely than their White counterparts to be murdered, and they constitute more than three quarters of homicide victims in the country.

A longstanding media crisis only exacerbates such patterns. Nearly two-thirds of all municipalities in Brazil qualify as “news deserts,” areas where there is little to no local coverage. Outlets with national reach end up being a community’s primary sources of news, but rarely address relevant issues in that community — such as the lack of food at a city’s public schools or untenable lines at health care institutions. Instead, national outlets only show up to report on violence, criminalizing, and even blaming residents.

The result is a fun house mirror of sorts, skewing residents’ realities and reflecting back a distorted version of their lives. “News deserts directly affect subjects’ understanding of reality,” says Wellington Hack, a journalist and researcher at Universidade Federal de Santa Maria. “Allied to this issue, we still have socioeconomic problems that a large part of the population — especially in developing countries — faces, such as poverty and difficult access to education.”

Without a local press, adds journalist Mariama Correia, who helped research a local journalism mapping project called Atlas da Notícia (News Atlas), “the population is poorly informed about the actions of local/regional public authorities, and this impacts the citizens’ decision-making capacity.”

Yet, change has begun to take root. A number of initiatives have emerged from these news deserts, seeking to give voice to those who are excluded. Even more, these projects — newspaper O Cidadão (The Citizen), news agencies Voz das Comunidades (Voice of the Communities), Coletivo Papo Reto (Straight Talk Collective), Énóis (It’s Us), Maré Vive (Maré Lives), and others — were created by the very communities who have been and continue to be affected by news deserts.

Papo Reto was born in 2013 in Complexo do Alemão, a group of favelas in Rio de Janeiro that the media consistently portrayed as dangerous and violent. The idea, says co-founder Raull Santiago, “was developed with the objective of organizing people, disputing narratives, showing that the favela is not the focus of problems — the absence of public policies for populations like the ones that come from where I come from is the real problem.”

Lana de Souza, another co-founder, points out that Papo Reto isn’t just journalists but activists as well. “The big difference is to be able to align these two areas of action,” she says, “to be able to make and think communication beyond the reportage.”

In order to align those areas, Papo Reto has developed a multimedia approach with the help of community networks in Complexo do Alemão. Filming and photographing alongside its reporting, Santiago says, allows for “video as evidence,” and enables the collective to “mobilize and bring residents together by denouncing how the state acts violently.”

“We need not to be only White, from the elite, formed by the best universities, knowing very little about Brazilian reality to be able to talk about it. A country with a majority of women, Black, and lower-class individuals have their stories told from perspectives that are not theirs.”

This sort of engaged journalism also inspired the formation of news agency Énóis 10 years ago in the São Paulo neighborhood of Capão Redondo — as well as a youth journalism school. “It was important to train these people to allow them to have the technique to tell stories from their points of view,” says founder Nina Weingrill.

The common characteristic to all of these communication initiatives is the idea of allowing those who actually live in the outskirts, favelas, and peripheries of big cities to have their own voice — to take back, in Souza’s words, “the concepts and prejudices related to the favela and the people who live in it.”

Unsurprisingly, given the massive socioeconomic and resource disparities in Brazil, race is an important element of this local news coverage. “We don’t have a specific area to talk about racism in itself at Papo Reto’s website because racism is a fundamental element of everything we talk about,” says Souza. “Who are the people who are dying in this war? It’s all related. When we talk about the war on drugs, like police operations that happen inside the favelas, it only happens because of racism.”

Recognizing race is crucial, in Weingrill’s view, because it helps address the longstanding status quo of Brazilian media. “We need not to be only White, from the elite, formed by the best universities knowing very little about Brazilian reality to be able to talk about it,” she says. “A country with a majority of women, Black, and lower-class individuals have their stories told from perspectives that are not theirs.”

In newspaper O Cidadão, which covers Rio de Janeiro’s Complexo da Maré, favela residents are not referred to as “others,” “witnesses,” or “victims” — they are the protagonists.

“The importance lies in empowering the peripheral population to make their own communication and to be able to counter how the ‘big media’ speaks of the favelas and peripheries as spaces of deprivation and violence,” says O Cidadão journalist Carolina Vaz. “Community media have more authority to talk about local issues, and more competence to do this in the format that most of their audience will understand.”

Traditional media’s failure to cover favela life also motivated the formation of Maré Vive, another community media organization in the same favela. “The corporate media shows only one side, the ‘official one,’” says a representative of the group. “it only listens to the side of the police, but won’t listen to our side.”

The group was born in 2014 after then-president Dilma Rousseff signed an order placing armed troops in the community. “Having a battle tank outside a school is not a normal thing,” the representative says. “This invasion led us to talk: taxi drivers, teachers, photographers, journalists, actors, housewives — we met to make collaborative coverage of this government action. ”

Thanks to the internet, other barriers have fallen as well. In 2005, Rene Silva founded Voz das Comunidades, a news site covering Complexo do Alemão, when he was 11 years old. Since 2010, the site has been receiving international attention for its coverage of the community — not just reporting the news, but also promoting charity events and creating awareness of the many issues residents face.

But age and location aside, all of these initiatives have one thing in common: they try, in Raull Santiago’s words, “to place the favela as the center of transformation and the construction of a more egalitarian and fairer country.” So far they have been achieving national and international praise — but more importantly, they have been giving voice to those otherwise excluded.