Everything looks more momentous in hindsight, but there’s no denying that February 11, 1990, contributed more than its share to the zeitgeist. Nelson Mandela was released from prison. Buster Douglas beat Mike Tyson. And a rapper and dancer from Oakland, California, dropped a rap album called Please Hammer Don’t Hurt ’Em. It wasn’t MC Hammer’s first success — his major label debut, Let’s Get It Started, had gone double platinum — but it would most definitely change things. Powered by the earworm that was “U Can’t Touch This,” PHDHE went on to become hip-hop’s first diamond-certified album, and with 18 million sold worldwide, still stands as the genre’s bestselling album of all time.

That’s not to say that it was all love for Hammer. The artist, the art, and the way he capitalized on his success all received blowback — from both hip-hop and the world at large. Thirty years is a long time, though, and while it’s easy to look back and dismiss the album as a long-ago trivia answer, it felt a little different for those who were there. Given that a few LEVEL editors were in high school when the album dropped, it felt only right to convene an old heads’ summit to revisit it all. Uh-oh, uh-oh, uh-oh, uh-oh…

Peter Rubin, executive editor: So let’s set the scene. February 1990: Where were we?

Aliya S. King, editor at large: I graduated from high school in June of 1990. So in February, I’m in East Orange, New Jersey, getting ready to finish up my last year — I just found out I’ll be going to Rutgers, so I’m pretty checked out of high school. I’m only 16, because I started school early, so I remember feeling really young and really old at the same time.

Peter: Finishing high school at 16 is crazy. Jermaine, were you on that prodigy tip too?

Jermaine Hall, editor in chief: I was not on that prodigy tip. I was a junior in high school at LaSalle Academy just trying to make it to track practice. Living in Queens, making that trek to Manhattan every day, just hoping that we didn’t get robbed by any Decepticons.

Aliya: [Laughs] Sorry, that’s not funny.

Peter: Decepts were out!

Jermaine: Yes, they were.

Peter: This brings up a caveat for this conversation: None of us are from the Bay Area, which gives people a completely different slant on Hammer’s role and what this album was — because you’re both East Coast and I’m from the Midwest. February 1990, that was my freshman year in high school. The thing that tipped me off about what was happening with the Hammer album was that that spring, the track team got “U Can’t Touch This” T-shirts.

Jermaine: Oh no!

Peter: And for that to happen in Indiana? This had hit a different level. Hammer had already dropped an album, so hip-hop knew him. “Turn This Mutha Out” had been huge.

Aliya: And “Pump It Up”!

Jermaine: “Pump It Up” was in heavy rotation — we had this thing in Queens called The Box; you could call a number and request videos.

Aliya: The Box is why Hammer became a thing on the East Coast! 2 Live Crew too.

Peter: The Box helped break a lot of regional acts — add Sir Mix-a-Lot to that list.

Aliya: The Box was pretty much social media. I would see it at my grandma’s house in Newark, and you could see who was calling in because you could see the phone numbers. “Dude, how you ordering from The Box when you said you was down South with your grandparents but I see your phone number poppin’ up?”

[Laughter]

Jermaine: I remember when I first saw “Pump It Up,” which was the first [Hammer video] playing heavy on The Box, I thought, “Damn, this dude can dance his ass off.” I don’t remember the lyrics because we always thought they were terrible. But dancing was a big thing for us. I remember buying the 33-inch to “Turn This Mutha Out.” I rocked with that record.

Aliya: I was looking at the album today and I cannot figure out how he was able to afford the samples he had — he samples “When Doves Cry”!

Peter: He used “When Doves Cry” and “Soft and Wet,” he used Rick James on “U Can’t Touch This,” he used “Mercy Mercy Me” —

Jermaine: Yoooo, “Help the Children”! That’s right!

Aliya: How was he able to do this? It’s 1990; by this point, you’ve got to open up your pocketbook to get a sample.

Peter: The year before, De La Soul’s first album had come out and that album had one of the first major lawsuits about sampling, right?

Aliya: And MC Hammer is not doing the Turtles! He’s using platinum songs from platinum acts!

Peter: So when “U Can’t Touch This” became as ubiquitous as it was, did it feel like the next logical step?

Aliya: East Coast kids were still very firmly, “This guy is wack. I don’t care how many commercials you got, I don’t care how many dancers you got.” By the time I started working at The Source in ’99, people were finally begrudgingly giving Hammer his props.

Jermaine: He did have love in the Bay. It could just be a very East Coast bias.

Peter: And he had gotten a reputation in the Bay by having a huge crew of dancers and backup performers [before] he was even signed — that was his live show. It’s crazy that all that pageantry was there from the beginning. But it felt like everybody else dissed him. 3rd Bass, LL Cool—

Jermaine: Serch and company definitely dissed him. In the “Gas Face” video, Serch uses an actual hammer, and they were literally kicking the hammer’s ass.

“I never expected lyrics from him; it was always more like a traveling Broadway show.”

Aliya: September 1990, I’m moving into my dorm. By this time, MC Hammer has just won the entire year. We can’t escape him. Everyone hates him, can’t escape him. Then A Tribe Called Quest drops “Check the Rhime,” and Q-Tip says, “Proper — what you say, Hammer? Proper.” Everyone thinks that’s a diss, but I saw Q-Tip as begrudgingly acknowledging him. He was never the thing for me, but I never did understand why people were so angry with this dude doing his thing. He wasn’t pretending to be anything. He wasn’t Vanilla Ice!

Peter: But it did feel like there was a culture war inside rap around it. It wasn’t about a coastal thing; it was completely an aesthetic-slash-sound thing.

Aliya: We were still looking for acceptance in a way that a lot of people didn’t admit. Who doesn’t want a Super Bowl commercial? The song “Pray”? That was the first and last rap song my dad — God rest his soul —would ever fuck with.

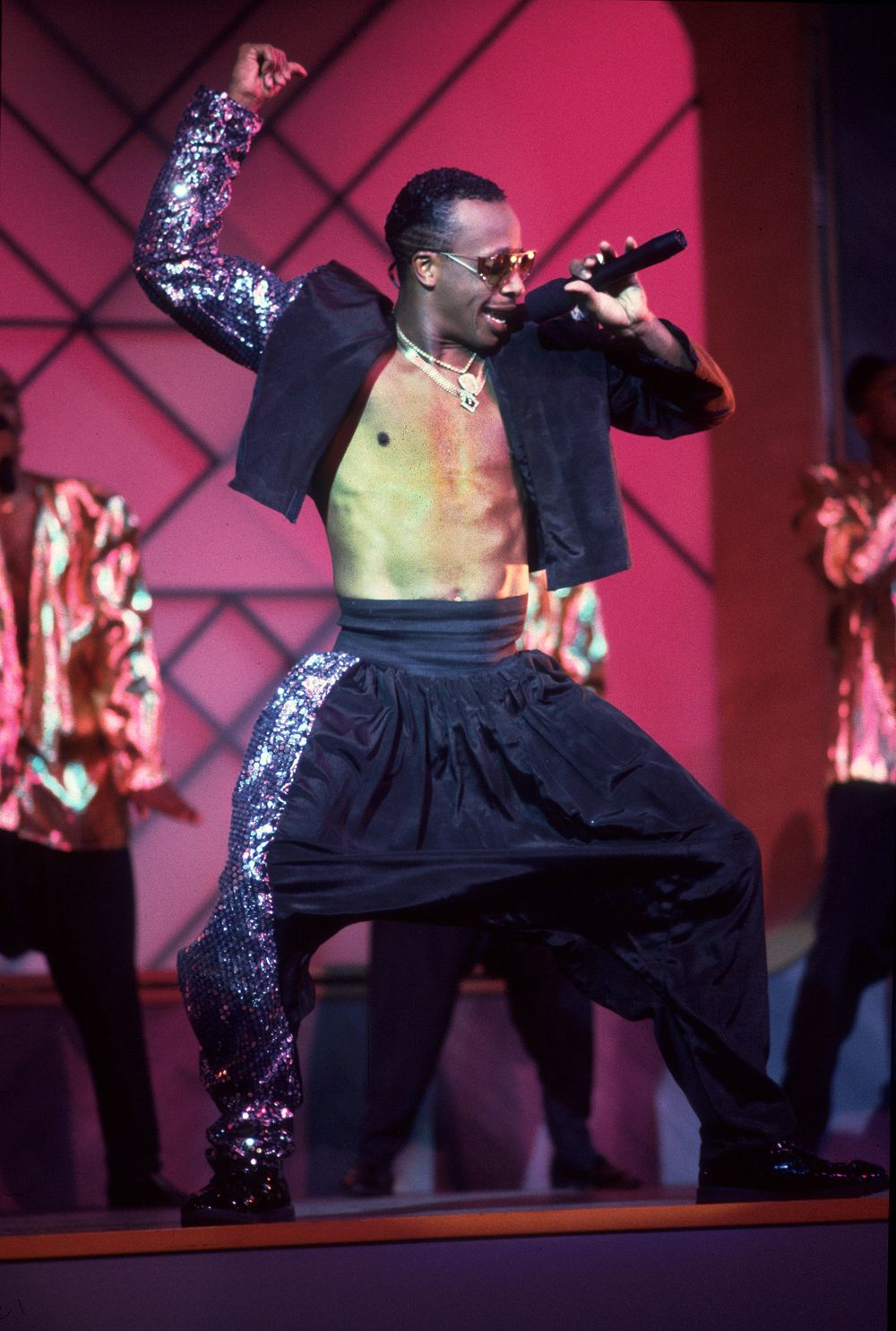

Jermaine: I never expected lyrics from him; it was always more like a traveling Broadway show. You knew the guy was gonna dance his ass off, you knew Oaktown’s 357 was gonna kill it. You have to respect the choreography that Hammer put together for those shows.

Aliya: I did not know where MC Hammer was from, and a lot of your appreciation for hip-hop was regionally based. So when NWA came out, even though they weren’t speaking to me, I respected that they were opening up this new world for me and I knew who they were talking to. So I never would have imagined back in 1989 to ’90 that he was from the hood. I really didn’t see it that way! I saw this as just some poppy guy from, I don’t know, someplace.

Peter: Also, we weren’t strangers to poppy sounding or dance-forward hip-hop — Kwame and Kid ‘n Play was all in the late ’80s, early ’90s. That up-tempo “let’s have a good time” vibe was around.

Jermaine: It’s not the sound, it’s the show production. Big Daddy Kane was a three-man production!

Aliya: And that was extravagant. “You got two dancers?!”

Jermaine: This dude had a whole squad of people dancing in unison. It was different!

Aliya: We were also in a time where you couldn’t really go outside cultural norms, and that’s all MC Hammer did. Nobody’s wearing Hammer pants until we see him wearing them.

Peter: That’s a great point. We were hearing Hammer in the context of all this other shit that we were steeped in — but meanwhile, little kids and parents are falling in love with Hammer. That shit was like “Baby Shark” and “Old Town Road” in one song.

Aliya: It was both — in one person with 25 backup dancers. Was “U Can’t Touch This” bigger than “Old Town Road”?

Peter: I just looked this up before we talked, thankfully: The song never went #1 on the Hot 100 — but the album spent 21 weeks at #1, including 18 consecutive weeks.

Aliya: Part of the reason why I think he was able to take over in this way is that for the most part 1990 is not a banner year for hip-hop.

Jermaine: But it’s “Super Freak”! The melody is undeniable. It’s gonna make you move.

Aliya: But hip-hop? We’re still reeling from 1988, and Wu-Tang is somewhere scratching its ass and preparing to get in the studio — and along with everybody else, is going to turn hip-hop on its head in ’94. But in ’90, it’s pretty quiet.

Peter: A Tribe Called Quest dropped their first album in ’90. Ice Cube’s first solo joint.

Jermaine: It’s not quiet on the West Coast.

Peter: 1990’s a weird one — there were big albums, like Fear of a Black Planet, but it’s not one of those mythical years like ’88 or ’92. It had these two huge crossover phenomena, though: Hammer and Vanilla Ice.

Aliya: There was no Biggie, there was no Pac, there was no Wu-Tang. There was no huge breaking act to take attention away from Hammer.

Jermaine: For us in Queens, it was that first Tribe album.

Aliya: But what new artist came out in 1990 and changed everything?

Peter: Everyone who dropped an album in 1990, it wasn’t their biggest album. Fear of a Black Planet was huge —

Aliya: — but Nation of Millions was a culture-defining album.

Peter: Exactly. People’s Instinctive Travels was big, but it wasn’t like Low End Theory. So big albums, but not necessarily one of those banner years. And into that comes Hammer. Not only does the album dominate the charts for a solid six months, but for the next year or two dude is everywhere. Commercials. A cartoon!

Aliya: One of the issues that people had with him — in hip-hop, anyway — was being a sellout. I always thought, “When did he ever sell in?” It’s not like he was a certain way and then switched up his style to get money. Him doing a KFC commercial was not Mary doing a commercial for Burger King crispy chicken — which turned out to be very problematic for her 20 years later.

Jermaine: It did ramp up with that second album — naturally, though.

Aliya: Do we think of him as a minstrel? Do we think that he was shucking and jiving and coonin’? Is that how we thought of him back then?

Peter: The commercials definitely represented a shift for me. Like when I saw dude using his Hammer pants to act as a parachute — I don’t even remember if that was Taco Bell or KFC, but I felt…

Aliya: Icky?

Jermaine: I don’t think that’s specific to Hammer. As a culture, we always have a problem once we see our people doing those commercials. Like Mary, we were like, “Nah, this is not it.” Maybe Pepsi and Michael? Maybe we accepted that one?

Peter: The Sprite ads that had like Grand Puba and Pete Rock were maybe the first ones I remember that I was like, “Oh, they’re doing this the right way.”

Jermaine: Sprite did it properly.

Peter: And then at some point, Puff could somehow appear in a Pepsi ad in a way that felt on brand.

Jermaine: It’s a money grab for these artists. Why wouldn’t they?

Aliya: Right, but hip-hop has never been forgiving of that stuff. We want you to get your money, but it has to be on our terms and in the way we think is acceptable. Was it around the same time that LL did the infamous Gap commercial with the Fubu hat on? We were all cheering for that because he was still speaking to us while he’s getting his check. So we appreciate that — but chicken is always gonna be problematic.

Jermaine: [Laughs] Don’t do it!

Aliya: That check is never gonna be worth it.

“We want you to get your money, but it has to be on our terms and in the way we think is acceptable.”

Peter: Jermaine, after we decided to do this, you put the album on in the car with your 13-year- old.

Jermaine: Jordan was not rockin’ with that.

[Laughter]

Peter: How does a kid today feel about Please Hammer Don’t Hurt ’Em?

Jermaine: He kept it really short — he was like, “This is wack,” and then he put his headphones on.

Aliya: What song was on?

Jermaine: We started from the very beginning, so it was maybe three or four in. “Yo Sweetness,” maybe?

Aliya: I’m intrigued by your knowledge of the album.

[Laughter]

Jermaine: It was so ubiquitous when it was out that you can’t help but remember them. I definitely remember the album starting with “Here Comes the Hammer.” And “Pray” was all over the place.

Aliya: You tell Jordan that he wouldn’t have been able to do that in 1990! If that was on the radio, you gotta sit the whole ride to school and back with that shit coming on every 10 seconds. Part of how we felt about him was that we couldn’t control how often we would see or hear him. It was up to the rest of the world. If we could’ve been streaming our own shit, maybe we wouldn’t have gotten sick of him!

Peter: And outside the New York area, there was still novelty to hearing rap on the radio. There was no free way to hear it for a lot of us — everything had to be tape-trading or just buying what we could. I didn’t have cable. I didn’t have videos other than what’s on at friends’ houses. So the videos weren’t getting worn out for me either.

Jermaine: I would buy a ton of Columbia House under different names.

Aliya: I still owe them money!

Peter: That was the hustle for sure.

Aliya: When I started playing the album this morning, my 12-year-old daughter had her headphones in. She took one out to hear what I was playing, immediately put it back in — but when “U Can’t Touch This” came on, she took her headphones out, and immediately started singing along and doing the Hammer dance, which I swear I had no idea she knew.

[Laughter]

Aliya: The whole thing — shoulder shimmying, all of it. She was like, “Mom, it was just a commercial.”

Jermaine: A Super Bowl commercial!

Peter: The gift that keeps on giving. So the fact that she knew the reference and knew the dance brings us to a good question. It’s easy to go back and say when we were 14, 15, 16 years old it hit us this way or that way, but 30 years later, what’s the legacy?

Jermaine: For me it was how far hip-hop could travel in a pop landscape. That’s what I took from it. Later we’d see what Puff could do when he came in but still stayed true to what the art form should be. Puff is sampling-insane too! He just had a different caliber of MCs to work with, to put on top of those beats.

Peter: This album was the peak of up-tempo hip-hop for sure—not in quality, but more of an inflection point. It set the stage for all the darker shit we would end up seeing with Big and Nas, and because of the way popularity breeds backlash maybe even helped ignite that grimier roughneck thing that East Coast rap grew into in the early ’90s.

Aliya: So for me, I think that considering where we are right now‚ — we all know that 2019 was Lil Nas X’s year — it’s prophetic, maybe? Is hip-hop proud of Lil Nas X? That’s what interests me, because I think by this point hip-hop is proud of Hammer. We want him to win. We’re not mad he did a Super Bowl commercial. Everyone who dissed him 30 years ago wishes they could count on a check every year based on a little dance that they made up. So I wonder for someone like Lil Nas X, who’s looked at as kitschy and who had a “Baby Shark” type of phenomenon just like Hammer — but where’s he gonna be in 30 years?

Peter: Plus the meme god has new platforms to extend his celebrity — which Hammer didn’t.

Aliya: Exactly. I’m curious to see what hip-hop will be for him, and how hip-hop will embrace him. Jermaine, 30 years from now, when your son and my daughter are our age, what’s going to be the conversation about him?