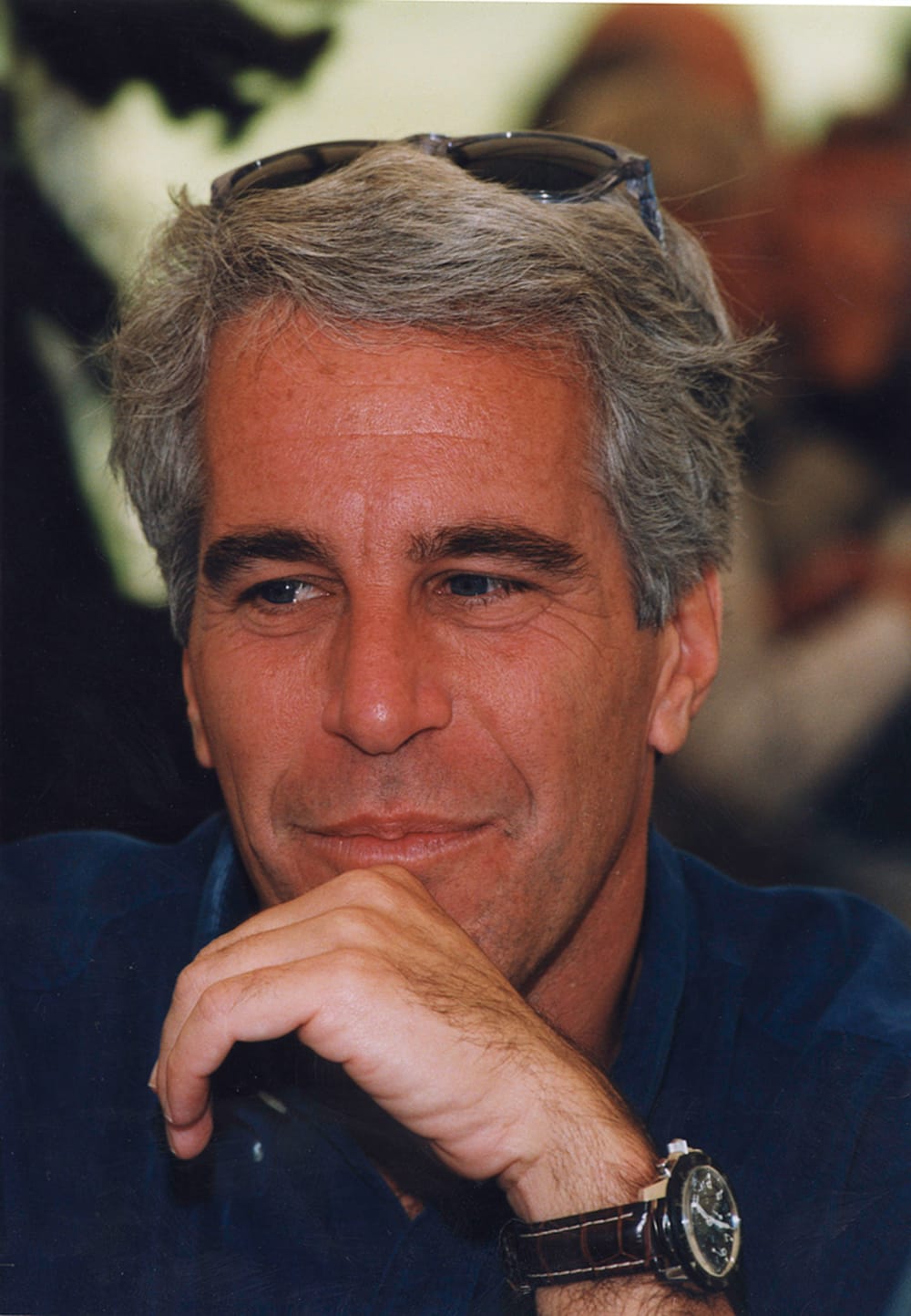

The least negative thing I can say about Jeffrey Epstein is that he certainly knew how to live large. At the peak of his holdings, Epstein owned a 7‑story Upper East Side Manhattan townhouse (9 East 71st Street), a waterfront Palm Beach mansion on El Brillo Way (358 El Brillo Way), an 800‑sqm luxury apartment on Avenue Foch in Paris, and the sprawling Zorro Ranch in New Mexico (about 10,000 acres with a 26,700–33,000 sq ft main house). Those properties don’t include Little St. James Island in the U.S. Virgin Islands, where the main compound was estimated at 20,000 sq ft, with multiple guest houses and staff buildings.

I’ve never lived in a mansion of any size, nor in any residence the size of Epstein’s dwellings (except the one in Paris). Still, I have watched The Gilded Age, Bridgerton, Downton Abbey, and Upstairs, Downstairs, which suggested that even in this modern era, it takes quite a staff to run those buildings, even when Epstein and Maxwell weren’t in residence.

Even before batches of the Epstein files were released, we’ve known the names of several of the workers who saw the comings and goings of Epstein’s visitors.

In New York, Lesley Groff was the executive assistant who worked out of the townhouse. Cimberly Espinosa was an office assistant who had testified in multiple civil cases. Epstein had drivers and security staff, some of whom were named in depositions.

In Palm Beach, Alfredo Rodriquez was the former house manager who kept a black book of contacts and notes. Rodriquez was arrested for obstruction when he tried to sell the book rather than turn it over. The book is allegedly in federal custody, but no portion of it has been released as part of the Epstein files. Nadia Marcinko lived in the house and has been described as an “assistant,” “girlfriend,” and sometimes a “co-conspirator” in court filings. Sarah Kellen was the scheduling assistant who managed the flow of girls and massage appointments. Adrianna Ross was a former Eastern European model who worked as a household assistant in Palm Beach. Kellen, Marcinko, Groff, and Ross are the four “co-conspirators” in the 2007–2008 federal non-prosecution agreement, which kept them from testifying against Epstein and others.

During the 2019 investigation, federal agents interviewed boat operators, groundskeepers, and maintenance workers. But none of these interviews have been released in full, and none of the staff have spoken publicly. On Little St. James Island, survivors have described housekeepers cleaning rooms after encounters. The staff were instructed never to speak to guests, workers were told to avoid certain buildings, and there were strict rules about where they could walk. Some staff reportedly quit abruptly after witnessing disturbing behavior. But almost none have spoken publicly.

Multiple sources describe a culture of non‑disclosure agreements, verbal warnings, strict compartmentalization, and fear of losing employment. Workers were told, “Don’t ask questions,” “Don’t talk to guests,” and to “Stay away from certain areas.” I believe that, like the staff on all the fictional shows I’ve watched, the Epstein staff knew all the inner workings of the operation and, like any good workers, learned to anticipate the needs of their boss and regular guests.

Overnight guests at an Epstein home would have been greeted, had their luggage brought to their room, and some would have scheduled massages. Repeat guests might request a particular girl. This would have been seen to by Sarah Kellen in Palm Beach and someone else at the other estates. Special needs would have been addressed, allergies noted, special diets accommodated, seating charts for meals prepared, and rooms assigned based on Epstein’s dictates.

The staff, including pilots, would have known who was coming and going and, in many cases, who they were with while at the estate. If investigators really wanted to know which men the girls were trafficked to, they could start by asking the people who know, along with a full release of the Epstein files, with the men’s names not redacted. The people currently testifying before House Committees are those least likely to say anything. Ghislaine Maxwell has already taken the 5th. Does anyone expect Bill and Hillary Clinton or Les Wexner to spill their guts? Donald Trump, who we learned was talking to the Palm Beach police about Epstein and Maxwell as early as 2006, could tell us a lot. He said everyone in Palm Beach and New York knew about how the girls were being used.

For all the headlines, all the court filings, and all the speculation about powerful men, the truth is that the people who could answer the simplest questions about what happened inside Epstein’s homes have never been asked — or never been required — to speak. The staff who changed the sheets, prepared the meals, scheduled the “appointments,” carried the luggage, cleaned the rooms, and watched the comings and goings were closer to the daily reality of Epstein’s operation than any lawyer, journalist, or investigator. They saw who arrived unannounced. They saw who stayed overnight. They saw which doors were closed, which rooms were avoided, and which girls were brought back again and again. They lived inside the machinery.

And yet, almost none of them have spoken publicly. Not the housekeepers on Little St. James. Not the groundskeepers or boat captains interviewed by federal agents. Not the assistants protected by the 2007–2008 non‑prosecution agreement. Not the workers who were told to keep their heads down and their mouths shut. Their silence is not mysterious — it is structural. It was built into the way Epstein operated, reinforced by NDAs, fear, dependency, and the knowledge that the people they served were powerful enough to make problems disappear.

But silence is not the same as ignorance. These workers know what investigators claim they cannot prove. They know which men were present, which girls were trafficked, and what patterns repeated across New York, Palm Beach, New Mexico, and the Virgin Islands. They know because they were there. And if the goal is truth — not mythmaking, not selective outrage, not another round of redacted files — then the path forward is obvious. Stop pretending the answers are unknowable. Stop shielding the people who enabled the system. And start asking the staff who lived inside it.

The story of Epstein and Maxwell is not just about one man and one woman. It’s about the network that protected him, the institutions that failed, and the workers who saw everything but were never permitted to speak. If we want accountability, their voices — not the sanitized files — is a source of truth.