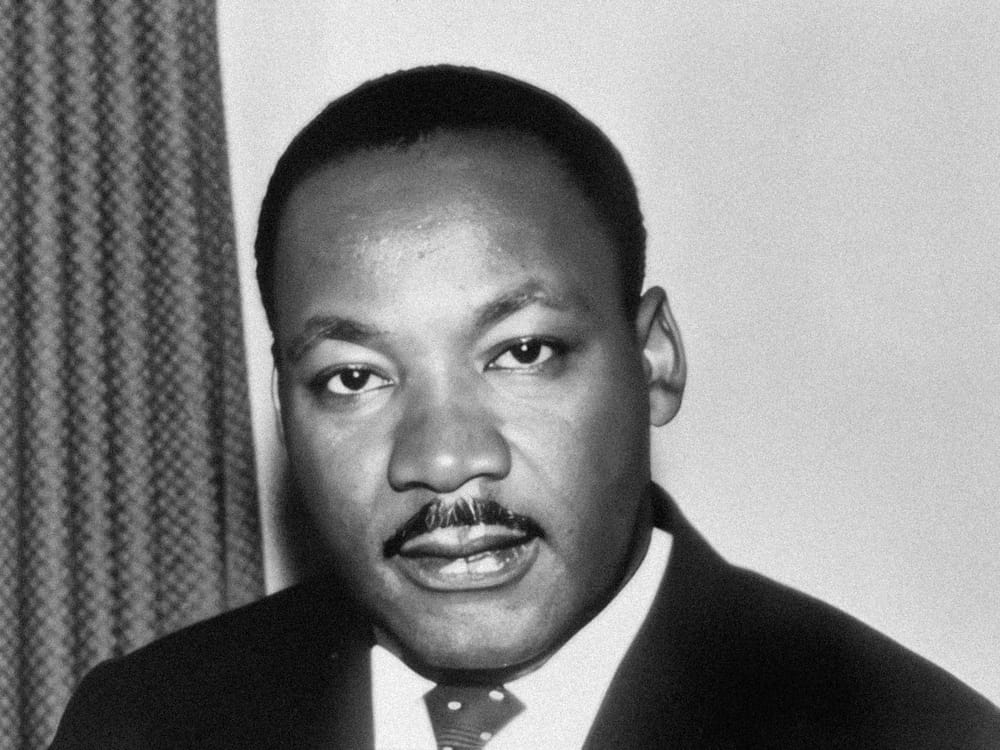

Martin Luther King, Jr was assassinated on April 4, 1968. The national holiday bearing his name was signed into law by Ronal Reagan in 1983 and recognized for the first time on January 20, 1986. It’s hard to conceive how much Dr. King was resented during his lifetime and after his death, given the frequency with which some of the same people quoted and misquoted him to make his legacy align with theirs. Most often cited is a passage from the “I Have a Dream” speech at the March on Washington in 1963.

"I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character," said King. "I have a dream today."

Rarely spoken of from the same speech is an earlier segment where he admonished America for what it had failed to accomplish in the 100 years since the Emancipation Proclamation. In the 60 years since his speech, Black people have fought and refought the same battles as Dr. King. Voter suppression, police brutality, mass incarceration, and income inequality are as prevalent today as then.

"But 100 years later, the Negro still is not free," said King. "One hundred years later, the life of the Negro is still sadly crippled by the manacles of segregation and the chains of discrimination. One hundred years later, the Negro lives on a lonely island of poverty in the midst of a vast ocean of material prosperity. One hundred years later the Negro is still languished in the corners of American society and finds himself in exile in his own land. And so we’ve come here today to dramatize a shameful condition. In a sense we’ve come to our nation’s capital to cash a check."

The first bill proposing MLK’s birthday as a federal holiday was brought to the House of Representatives by John Conyers of Michigan on April 8, 1968, four days after King’s assassination. It wasn’t even given a floor vote. Conyers reintroduced a bill every year, finally getting a vote in 1979. The measure fell five votes short of passage.

Related: The MLK Day of Service Forgets What King Stood For

J. Edgar Hoover, the director of the FBI, was out to destroy MLK. He was worried King might align himself with the Communist Party despite King’s constant preaching that Communism wasn’t consistent with Christian values. Hoover wiretapped King and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) he helped found in search of Communist ties. To be fair to Hoover, he infiltrated every Black organization, including the NAACP, C.O.R.E., student, and church organizations, along with the Ku Klux Klan and the American Indian Movement.

Alongside COINTELPRO, Hoover operated the Ghetto Informant Program, placing over 7,000 informants in poor Black communities across the country. Hoover tapped King’s phones and bugged his home and hotel rooms, sending advanced crews to every city he went to keep tabs. Upon discovering evidence of his infidelity, Hoover sent tapes to Coretta Scott King, Martin’s wife, and had sent a letter encouraging him to commit suicide.

The effort to create an MLK holiday picked up steam after the first vote failed in the House of Representatives in 1979. The King Center turned to support from the corporate community and the general public. Stevie Wonder released the single “Happy Birthday” to popularize the campaign in 1980 and hosted the Rally for Peace Press Conference in 1981. A petition with over 6 million signatures was circulated, the largest in favor of an issue in U.S. history. There were also detractors, including John McCain, who voted against the national holiday in 1983 but later voted for his home state of Arizona, recognizing a state holiday.

“We can be slow as well to give greatness its due, a mistake I myself made long ago when I voted against a federal holiday in memory of Dr. King," said McCain. "I was wrong, and eventually realized it in time to give full support — full support — for a state holiday in my home state of Arizona. I’d remind you that we can all be a little late sometimes in doing the right thing, and Dr. King understood this about his fellow Americans.”

North Carolina Senator Jesse Helms never wavered in opposing the holiday. Helms led a filibuster in the Senate that almost derailed the vote. He produced a 300-page report insisting King was a Communist that contained no proof. New York Democrat Sen. Daniel Patrick Moynihan threw the binder of reports about King to the floor in the Senate chamber, calling them “filth.” Helms called for the early release of other FBI files, which he believed would prove Dr. King’s ties to Communism.

The same Ronald Reagan who signed the bill initially opposed the holiday. When asked about reports that MLK was a Communist, Reagan replied, “We’ll know in about 35 years, won’t we?” That was when those documents were scheduled to be unsealed. They ultimately were unsealed, and instead of showing King was a Communist, they revealed the extent to which the FBI hounded him and others.

When MLK Day became a federal holiday in 1986, in several states, the holiday was shared with others who didn’t embody the same spirit. When states were called upon to create state holidays, some balked while others tainted the day, making him share it with Confederate heroes like Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson. Alabama would establish “Robert E Lee/Martin Luther King Birthday Day,” with Lee given top billing. Arkansas had “Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s Birthday and Robert E. Lee’s Birthday,” Idaho had “Martin Luther King Jr.–Idaho Human Rights Day,” Virginia had “Lee–Jackson–King Day,” with King listed last. The disrespect could be cut with a knife.

The National Football League found itself embroiled in the controversy surrounding the holiday. In 1990, the NFL awarded the 1993 game to Phoenix, contingent upon Arizona establishing an MLK holiday. Arizona had yet to recognize the holiday, and the NFL didn’t want their premier event marred by protests and boycotts. Arizona voted down the holiday, and the 1993 Super Bowl was moved to the Rose Bowl in Pasadena, CA.

Coincidentally, I owned a merchandising company that sold licensed merchandise at special events like concerts and sports events at arenas and stadiums near Orlando, FL, where I lived. At some buildings, I was the joint venture partner of a California-based company called Facilities Merchandising, Inc. (FMI) that contracted with the NFL to sell merchandise at the Super Bowl, wherever it was held. FMI brought managers from buildings they operated nationwide to work the Super Bowl, and the NFL was their highest-profile client.

Related: Why they Fear Coach Prime

There was a lot of publicity regarding MLK Day surrounding the game, partly because it was only there because it was moved from Arizona. This was my third Super Bowl worked, and we had a routine. I flew into Los Angeles on Saturday, January 16. I caught wind while changing planes that the Buffalo Bills would likely be the AFC Champion; the NFC Champion would be determined the next day. The NFC Champion turned out to be the Dallas Cowboys.

Sunday the 17th was a work day. The Rose Bowl Stadium looks beautiful on television, but it’s antiquated and has no space to accommodate the merchandise sold at a Super Bowl. We were set up in a 10,000-square-foot tent in a field across the L. A. River, about a half-mile from the stadium. Our first couple of days consisted of receiving the generic Super Bowl merchandise; once the teams were identified, the team merchandise arrived. We had to piece-count everything that came in, then issue it to pallets that would ultimately be sent to merchandise stands. Because Dallas was one of the teams, sales were expected to be high, and they were. My point is that the first days on site would be hectic, including MLK Day, our second day of work on Monday, January 18 of that year.

On Sunday, the President of FMI, Milt Arensen, approached me and another Black manager, Wayne, who worked for me in Orlando, to ask if we wanted to take off MLK Day. Milt is Jewish; you’d never consider him religious, though his son’s Bar Mitzvah was important to him. He didn’t travel to Orlando once for a scheduled presentation regarding our contract to the City of Orlando because it fell on a Jewish holiday. Wayne and I had never considered that MLK Day would be anything other than a work day. It was awkward for Milt because he could not gauge how significant the day might be to us. We thought we’d be letting down our co-workers, who were friends, as we’d worked together at other events. Taking the day off would have meant sitting in a hotel watching television without transportation while creating more work for everyone else. We declined to take off but appreciated the thought.

Related: Why I Will Never, Ever Work on MLK Day

In many respects, MLK Day has become just another holiday. Most states have dropped their ties to Confederate heroes. There are furniture, automobile, and mattress sales. Federal employees get the day off. After that, it’s hit or miss, depending on your state or company. King has become a hero of those who oppose much of what he stood for.

Last year, Marjorie Taylor Greene praised King while suggesting a new kind of tyranny binds us related to vaccinations. Ron DeSantis claimed MLK would love his bill banning books on Black history. A few years ago, Donald Trump commemorated MLK Day, a day after calling African nations “shithole countries.”

Martin Luther King Day is celebrated on the third Monday in January yearly. This year, it falls on his birthday, January 15. King shares his day with Robert E. Lee in Alabama and Mississippi, so there’s still work. Virginia has given Lee and Stonewall Jackson their own day, the second Friday in January. MLK Day has been joined by the Juneteenth federal holiday every June. Despite the altruistic reasons for celebrating when Texas learned of the end of slavery after the Civil War. I submit it only became a holiday in response to the millions of citizens protesting the George Floyd murder in streets around the world.

Related: White People Should Have to Work on Juneteenth

Juneteenth and MLK Day represent the illusion of change given when real change proved too hard. With each passing year, King’s legacy is homogenized, and MLK Day can now be found on Hallmark Cards. Let’s continue celebrating the day but not stray from the man’s mission. There was reason to celebrate when it first passed, but things shouldn’t end there. MLK Day is a reminder that the goal wasn’t accomplished in the first 100 years after enslavement or the next sixty until the present. It will indeed be a celebration when King’s dream becomes a reality for all and more than just a slogan.

This post originally appeared on Medium and is edited and republished with author's permission. Read more of William Spivey's work on Medium. And if you dig his words, buy the man a coffee.