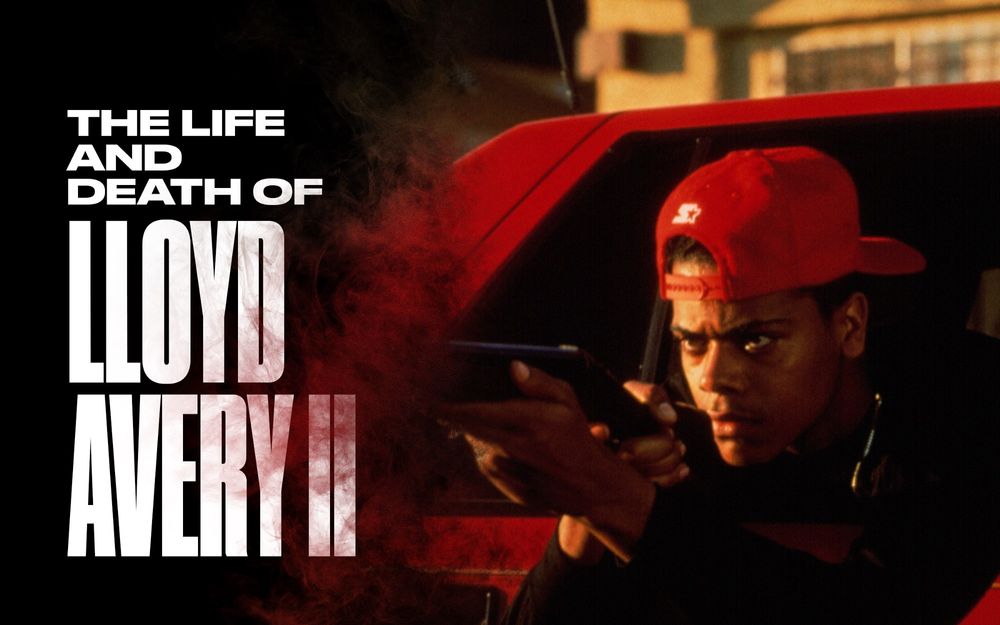

Based on numbers alone, Lloyd Avery II’s character in Boyz N the Hood is a minor role. Four scenes. About eight lines of dialogue. At most, two minutes of screen time. He’s listed in the credits as Knucklehead #2, but fans of the film know him as the Blood who shot Ricky. He’s best remembered emerging from that cardinal red Hyundai clutching a sawed-off shotgun like he’s death incarnate, set to perpetrate one of the most tragic movie murders of all time. Radiating intensity, Avery’s charisma elevates this nameless henchman into an iconic villain.

“Lloyd had a presence that I think was undeniable,” says Robi Reed, the veteran casting director known for her work with Spike Lee and other Black filmmakers. “When people refer to that ‘it’ factor, it’s really intangible — you just know when you see it.”

Avery’s breakthrough occurred in one of the most important films of the 1990s. Boyz N the Hood earned John Singleton, its 23-year-old writer and director, Academy Award nominations for Best Director and Best Original Screenplay. It also made a ton of dough (more than $57 million at the domestic box office against a $6 million budget) and catapulted the film careers of Singleton, Angela Bassett, Ice Cube, Morris Chestnut, Nia Long, and future Academy Award winners Cuba Gooding Jr. and Regina King.

Boyz N the Hood changed Avery’s life as well. But all he got was a rep. Soon after the film’s 1991 release, Avery moved into the Jungle, a Bloods-affiliated neighborhood in South Los Angeles, where he was said to have connections with the Black P-Stone set. He often wore red with Chuck Taylors and khakis and grew so affixed to the streets that he had “JUNGLEZ” tattooed above his left eyebrow. In other words, the actor who played the Blood who shot Ricky had turned into The Blood Who Shot Ricky.

Avery was couch-surfing with friends and family when the wanted posters went up in the fall of 1999. Now a struggling actor and rapper, he seemed personally and professionally lost since his debut in Boyz. “People I ran into were always like, ‘What’s going on with Lloyd? It seems like he’s self-destructing,’” says his younger brother, Che Avery.

Avery’s behavior had turned alarming, even for someone with a tattoo on his face. Since turning 30 in June 1999, Avery had been fired from a film for accidentally breaking into a prison and nearly dismissed from another after threatening to murder the director. He left his longtime apartment to share a Hollywood crash pad with four surfer bros he just met. That arrangement ended when he maced his roommate’s mom. He also maced former MTV VJ Downtown Julie Brown at a nightclub.

He stole a bike to get to work. He stole a car to get to work. He was said to have packed a gun to a casting call and a witness said he wielded a gun during an argument on the Venice Beach boardwalk. He was violent one minute, then weepy and contrite. He also started going to church, though he rarely made it inside the building. “He would get dressed, go, be there, but would leave prior to the lesson and walk around the grounds,” Carol Avery, his aunt, remembers. “I figured he was struggling and Satan was pulling at him to keep him from hearing the lesson.”

The past was catching up with Avery, and he knew it. All the while, he was harboring a secret.

The murders occurred on July 1, 1999, in the Jungle. According to police reports, at around 4 p.m., Avery approached Annette Lewis and Percy Branch, who were sitting under a tree near Santa Barbara Plaza. After a short argument, allegedly over a drug debt, Avery pulled out a .45 caliber pistol and fired at Lewis before shooting Branch in the stomach. Lewis died later that day. Branch passed away three weeks later due to complications from his gunshot wounds.

Avery didn’t exactly go into hiding afterward. He filmed two movies while on the run and pursued his film career up until his arrest on the morning of December 8, 1999, following a police chase outside of his grandmother’s home near Beverly Hills. Sentenced to life in prison following a trial in December 2000, Avery’s downfall was complete. But another Lloyd Avery emerged in jail: a devout Christian nicknamed Baby Jesus. His bid for redemption, however, ended on September 4, 2005, at the hands of his cellmate, Kevin Roby, a devil worshipper who signed his name “Satannic Christ.”

Though some questions surrounding his death have never been answered — including who decided it was a good idea for Baby Jesus to share a cell with Satannic Christ — Avery’s loved ones still grapple with how he landed in prison in the first place. “No one could put their finger on it,” says Doran Reed, the brother of casting director Robi Reed and one of Avery’s closest friends. “People that knew Lloyd were like, ‘What the fuck? How did Lloyd turn into a gangster?’”

In the 15 years since Avery’s murder, he’s become a hood legend and an internet phenomenon of sorts. A YouTube video from April 2020 titled “The Story of Lloyd Avery” has received more than 4.8 million views. Predictably, he’s also a meme. I first wrote about Avery in 2007 for KING magazine, and his story has stuck with me ever since. When I started re-reporting the story last fall, the goal was to answer Doran Reed’s question: How did Lloyd Avery turn into a gangster?

Consider this a spoiler alert: There is no consensus as to what caused his breakdown. Among the reasons his friends, family, and colleagues cite are a bad breakup, bipolar disorder, a chemical imbalance, general mental health issues, daddy issues, the hood, the movies, hood movies, gang culture, hip-hop culture, drugs, and disappointment over his career. No single incident triggered Avery to break bad. Avery’s journey from Hollywood to Pelican Bay State Prison is a complicated one.

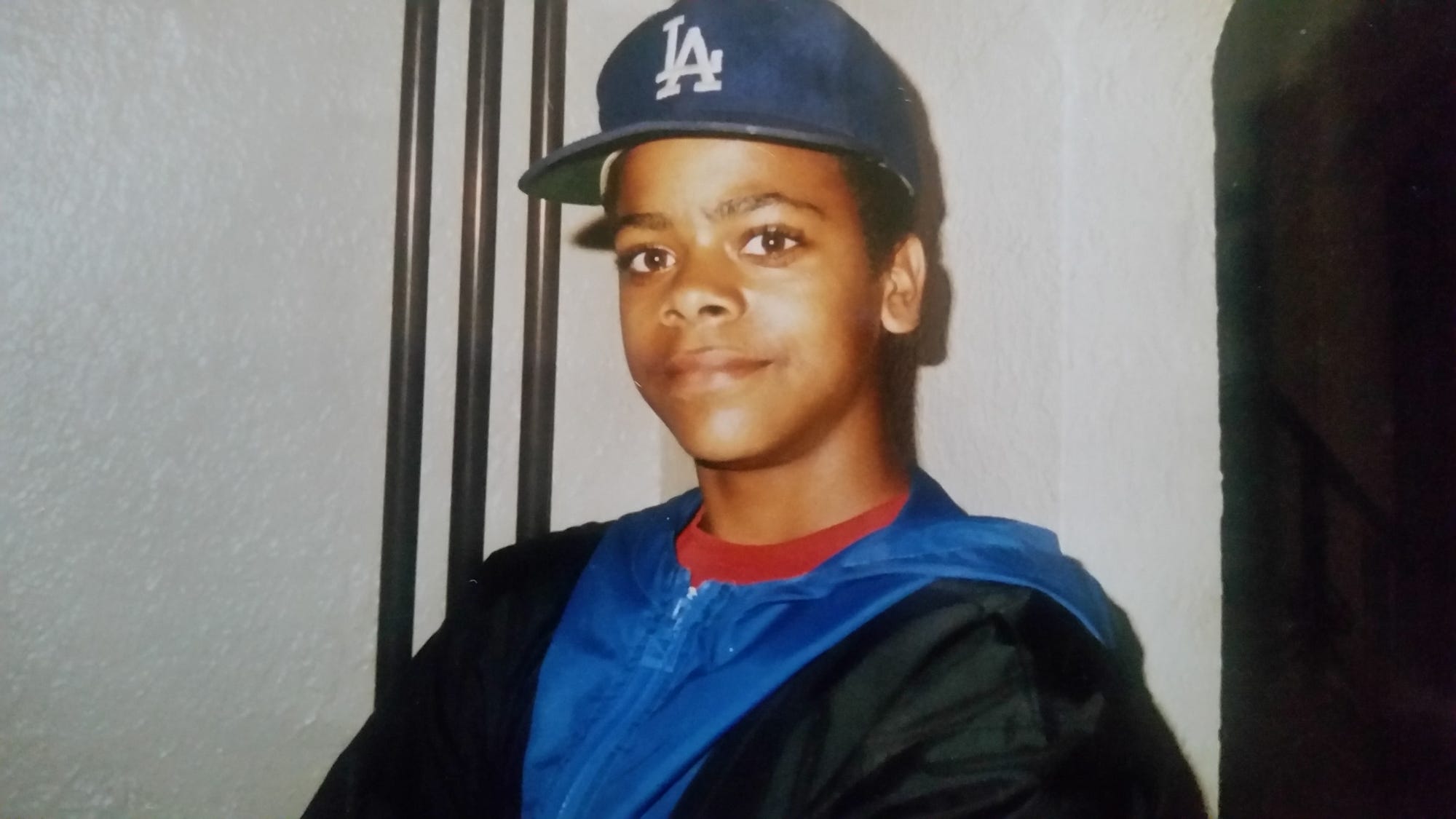

He wasn’t raised a gangster let alone a killer. Avery grew up with a pool in his backyard in View Park, a working-class L.A. neighborhood next to Baldwin Hills, aka the Black Beverly Hills. “We were silver spoon kids,” Che says. “We never needed for nothing.”

Lloyd Avery Sr. was an expert plumber, electrician, and carpenter with his own business while Linda Avery was a stay-at-home mom until the late 1980s, at which point she got a job at a bank. A good education took precedence in their household, and she enrolled the children into school integration programs. As a result, Lloyd Avery attended Beverly Hills High School. There, he lettered in baseball and water polo. For kicks, he sometimes did donuts near the swim gym in his brown Pinto. He could be shy, but more often than not, he was the class clown snapping jokes. He was a fun person to sit next to during a lecture. And though he didn’t date much, the girls loved him and his long eyelashes.

BHHS was not unlike the fictitious West Beverly High School on Beverly Hills 90210, where privileged scions cruised campus in their Beamers, Benzes, and Bentleys. Avery comfortably navigated this world despite his blue-collar roots and the brown Pinto. The children of Quincy Jones, Smokey Robinson, and Clarence Avant were among his closest friends.

The students attended house parties on the weekends, gathering in mansions while the parents vacationed in Palm Springs or Cabo. It was all unsupervised and a little seedy, complete with bathroom hookups and lines of coke in the laundry room — that Less Than Zero scene. Avery didn’t drink or do drugs. He instead played a game called party and pouch. “Steal shit at parties just to steal shit,” Doran Reed explains.

Avery was more of an attention-getter than an aspiring criminal. An agitator with a high-pitched laugh, he wasn’t interested in gang culture until after Boyz. That didn’t mean things never got violent. Comedian Robin Harris once attacked Avery at a Jet magazine photoshoot minutes after meeting him. “I don’t know what Lloyd said to him,” says Avery’s friend Brent Rollins, the art director and graphic designer who created the logo for Boyz N the Hood. “All I remember is that Robin Harris was choking him against a sofa.”

Avery had a gift for probing insecurities, sarcasm, pushing buttons, and incessant needling to provoke a reaction. But that was just one part of his personality. “He had a mischievous streak and a really sweet streak,” Rollins says. “The day before Christmas Eve, he would drive around to people’s houses to give them Christmas cards. Who does that?”

Avery was impulsive, often causing plans to go awry. It’s how he landed in jail for the first time. One night in 1988, Avery, Doran Reed, and some friends were leaving a UCLA party in Westwood when a group of frat brothers approached. Avery made a crack, words were exchanged, and a fight erupted. Three gunshots then rang out just as a patrol car roared down the street. Avery, who didn’t fire the weapon but was carrying a fake ID, spent three days in jail. His friends grew concerned afterward, not so much because of what happened but because of his reaction to it.

“What scared me was that Lloyd was laughing about it,” says Avery’s friend Keith Davis. “He told me that he really liked jail. It’s like, how the hell do you get locked up and you just enjoy it? He was so flippant.”

Avery worked gigs alongside his dad after dropping out of Los Angeles Trade-Technical College, but he didn’t want to follow in his father’s footsteps despite being a gifted handyman in his own right. Avery’s passion was music. Lloyd Sr. disapproved, so much so that he once took a baseball bat to his son’s SP1200. “He wasn’t all that happy with the choices Lloyd had made,” Linda Avery says. “But what his father wanted for Lloyd wasn’t for Lloyd.” Avery learned a lesson from the incident, though not the one his father intended. In June 1990, he was arrested for stealing studio equipment from a Guitar Center.

Around this time, Avery got his big break. His friend John Singleton was making his first feature film. As Avery put it during his murder trial, “I met the right person at the right time, and they put me in a movie.” When they met, Singleton, an Inglewood native, was the star of the Filmic Writing program at USC and a two-time winner of the Jack Nicholson Screenwriting Award. He combined prodigious talent with what could be called a monomaniacal drive to make movies. Shortly after graduation, Columbia Pictures agreed to film Singleton’s script for Boyz N the Hood with him as the director.

Like most locals in the cast, Avery was on set to show support whether he appeared on the day’s call sheet or not. Co-stars remember him as affable and humble. He took direction well from Singleton, who meticulously prepared Avery for his big scene: how to point the gun. What to do with his eyes. How to appear simultaneously cold-hearted and menacing because there is a difference between the two miens. No detail was too small. The day did not get off to a promising start though. Cuba Gooding Jr., whose character was preparing to witness his best friend’s murder, was a method actor at this point in his career and sat in his trailer brooding all morning. When Avery greeted him before shooting started, Gooding snapped, “Don’t fucking talk to me right now!” A production assistant diffused the situation.

Despite the friction on set, the resulting scene is a seminar on building tension, culminating in Avery’s appearance. “That shot of him out the window holding the gun is iconic,” says Malcolm Norrington, a college friend of Singleton’s who played Knucklehead #1. “John was so happy when he got that shot.”

Boyz N the Hood made Avery an instant celebrity around Los Angeles. At 6’1” with hazel eyes, he was easily recognizable and glided past the velvet rope at nightclubs. Initially, he enjoyed the newfound fame and aspired to capitalize on it. He hired an agent and went on auditions. The future seemed unlimited. “A very handsome young man,” Boyz N the Hood casting director Jaki Brown once wrote me over email. “I remember thinking, with more acting experience he would be a leading man one day.” Avery’s music career began to take off during this time as he produced “Push,” the lead single on actress Tisha Campbell’s debut album, Tisha. A blast of New Jack Swing, it was featured on an episode of Martin.

As for Avery’s next acting gig, he was cast in Singleton’s follow-up, Poetic Justice. The role of Thug #1 hardly sounds like a step up from Knucklehead #2, but it was part of Singleton’s plan to nurture Avery, who was, after all, an untrained actor. Avery’s cameo, where he once again murdered an innocent character, is the sturdiest thread connecting Poetic Justice to Boyz N the Hood. It’s a far different film from Singleton’s debut. A road-trip movie and love story, Poetic Justice centers on themes like loneliness and trust and features Maya Angelou’s poetry. It’s quieter and slower than Boyz but also unfocused. The film bombed with critics and underperformed at the box office.

Poetic Justice disappointed Avery as well, and he let Singleton, and everyone else at the film’s premiere, know. As the closing credits rolled, Avery stood and shouted, “That shit was wack, John.” The incident didn’t end Avery’s friendship with Singleton, but it was the latest instance of “Lloyd being Lloyd,” as the actor’s inappropriate outbursts were termed.

Avery was now staying with Quincy Jones III, the producer and filmmaker known as QDIII, in the Jungle, where Avery already was a legend because of Boyz N the Hood. “He probably got a pass for the fact that he killed someone as a Blood on film,” says Baldwin C. Sykes, a Compton native who played Monster in Boyz and says he receives similar treatment because of his actions on film. “Up to this day, I have people say, ‘Monster, you shot the Blood — you represented. You should be down with my hood.’ And I’m like, ‘I’m not down with a hood. That was an acting role.’”

Avery had a different response. Knucklehead #2 was his claim to fame. It defined him. If he wanted to be famous, he could relive that moment. And that’s what happened.

His friend Keith Davis remembers the first time Avery claimed Blood. “We were shopping at the Slauson Swap Meet,” he says. “Some Rollin’ 60s came up and were like, ‘You’re the guy from Boyz N the Hood?’ ‘Yeah, that was me.’ ‘You shot Ricky, right?’ ‘Yeah, that was me.’ ‘Hey cuz, you really a Blood?’ ‘Yeah, what’s up, Blood?’ I was looking at him like, ‘What?’ Lloyd just kinda laughed. They asked him if he was a Blood, and it clicked, ‘Yeah, I’m a Blood now.’”

It made little sense and not just because Avery grew up near Crip territory. He knew the hazards of gangbanging. The streets had already claimed his younger brother.

Che Avery was admitted to UC Berkeley and UCLA after notching a 3.6 GPA at Beverly Hills High. He didn’t attend either school, though. As he stated in a Los Angeles Times article from 1992, he “just felt some kind of attraction to the streets.” Unlike his brother, he didn’t befriend the rich kids at BHHS, though he says he partied with a Menendez brother on prom night. He dressed in Eazy-E cosplay, and while he wasn’t gangbanging yet, he felt he had an image to live up to.

He formed a crew, the DGFs, which stood for Don’t Give a Fucks. Each night promised a new adventure, with the DGFs looking for trouble after getting wasted on Olde English. In time, Che became feared. “Che once came to a party with Lloyd and I,” Doran Reed says. “This whole other gang is there. All of a sudden, Che starts throwing rocks at them. The other gang was like, ‘What the fuck is going on?’ One of them recognizes Che and was like, ‘Che? Oh, let it go.’ That whole gang was there, and they didn’t fuck with Che. That’s a little insight into how crazy Che was.”

Che graduated from the DGFs into the Rollin’ 60s, the notorious Crip set from the other side of Slauson. Now he was expected to put in work, a nebulous term that even now Che struggles to define. “If you wanted to establish yourself as someone in your hood to be reckoned with, if you wanted to earn your stripes or even give your neighborhood a name, if you from a neighborhood and you already have a reputation of being troublemakers or being the toughest, then you have to not only defend your neighborhood but let’s go over here to such-and-such’s neighborhood and put in work without saying too much. Put in work — terrorize them, whatever comes with that.”

In essence, putting in work is the price for acceptance and the camaraderie that comes with it all, which is the gang’s chief appeal. But putting in work invites retaliation, as Che learned. He lost two close friends to gang violence in the summer of 1990. Afterward, he was consumed with rage. He started carrying a .22-caliber revolver, which made him feel invincible. A series of armed robberies and B&Es followed.

Thirty years later, he feels lucky to be alive. “All of the stupid nights just doing stupid, stupid shit, every fucking night,” he says from his Augusta, Georgia, home. “Just senseless. Senseless, brother.” Che is a man of a certain era. Call him a throwback, that dude in grease-stained overalls who can fix anything. When I mentioned that I was insulating my bedroom, he interrogated me about foam caulk and the air conditioner sleeves found in Bronx apartments. “Che was like some sort of savant,” Brent Rollins says.

Despite his wild early adulthood, he had the sagacity to know that the streets were a dead end, and he renounced gang life before pleading guilty to nine felony charges of armed robbery. Over the next four-plus years, he bounced around the California penal system: Chino, Richard J. Donovan, and Jamestown, where he fought fires alongside other inmates. Prison was cruel — a Mexican gang robbed him for $40, a cellie ratted him out for sharpening shanks, he did a stint in the hole — but he grew as a person while incarcerated. The man once dubbed BK (as in Blood Killer) befriended members of former rival sets and learned carpentry and cabinet making, adding to the skills he accrued under his father and at Trade Tech. And when he was released from prison in March 1996, he vowed to finish school, start a business, work hard, be a good man, a good son, and never go back in. But much had changed in his family during the past 57 months.

“When I went to jail, Lloyd was a goody-two-shoes,” he says. “By the time I got out, he already had a case.”

Lloyd Avery, in fact, had multiple cases when his brother was released from prison, and he soon added burglary and weapons possession charges to his arrest record. QDIII once compared his former roommate’s way of life in the Jungle to that of Bishop in Juice. Every day got a little crazier.

Much of Avery’s aggression stemmed from the fact that he wanted to be a star and was coming to terms with the realization that it wasn’t happening. Opportunities like Boyz N the Hood had come so easily that he believed it would always be that way. He didn’t prepare for auditions — that is, when he bothered showing up. “I auditioned him once,” Doran Reed says, “and if that’s how he was auditioning, he wasn’t going to get anything.”

What Avery excelled at was burning bridges. Singleton was fond of Avery and found his practical jokes endearing, like the late-night prank call that led to the filmmaker directing Michael Jackson’s “Remember the Time” video (a story he recounted in 2017 on The Real). But Avery continued antagonizing him even after his stunt at the Poetic Justice premiere. “He called John ‘a punk ass nigga,’” Norrington says. “It got to the point where John stopped taking Lloyd’s calls.”

Avery’s music career had also stalled despite his industry connections. And so he doubled down on the streets, and the streets embraced him.

When he moved into the Jungle, he had the respect of an OG due to a murder he committed on film, but Avery wanted to earn his stripes. He put in work, and the BGs showered him with the attention he craved; Che Avery says he once came across someone with Avery’s face tattooed on his forearm. Avery also had ink done, tattooing the letter “J” in Olde English font above his left eyebrow. A few weeks later, he filled in the rest.

There was no shortage of people who grew up with Avery who wanted to help him, but as his best friends grew up and, for the most part, moved on, he became increasingly isolated. Even QDIII distanced himself from him. “He would call my house at random and be like, ‘I’m the king of the streets. I’m the hardest,’” QDIII once told me. “I told him everything is all good, but I had to take a break.”

At the start of ’99, as he approached turning 30, Avery lived alone in an office building in Santa Barbara Plaza with a shared bathroom down the hall. For money, he cashed small residual checks and washed cars for $5 a pop. Police believe he also sold crack.

Avery could’ve done as his brother had and returned to school. In March 1999, Che, now the father of a two-year-old son, won a Trade Tech scholarship and was gifted $2,500 in tools. His brother Zanjay and little sister Tikco had also graduated from college, but Lloyd fell deeper into the streets.

Avery fled the Jungle in April 1999 after an altercation with members of the Nation of Islam. He cleaned out his apartment in the middle of the night and stayed at his grandmother’s house until receiving some unexpected good news: He had booked a movie in New Mexico.

Filming on Lockdown started on July 14, 1999–13 days after the murders of Lewis and Branch — in Cell Block 4 of the Penitentiary of New Mexico. The location was the scene of one of the deadliest prison riots in United States history. Known as the Old Main, this section of the prison was shuttered in 1998. Still, reminders of the violence lingered, like the ax marks from where snitches were decapitated. It was an anxious set. At the end of the day, the crew would often unwind at a bar.

Avery preferred to remain in his hotel room. On the one occasion he attended, he ended up fighting actor De’Aundre Bonds. Chris, the tattoo artist on set, broke up the scuffle, leading to Avery feuding with the hair and makeup department. “He said he was going to find me and my family when we got back to L.A.,” says makeup artist Melanie Mills, “and that he was going to murder us.”

Avery was already a pariah on set. He scrapped with Gabriel Casseus following their fight scene, threw a tantrum after filming the scene during which his character was thrown into a freezer, and continuously riled Master P, one of the stars and producers of the film. “P’s guys would come to me and say, ‘Do you want us to fuck him up?’” director John Luessenhop says. “‘No, please leave him alone.’” In response, the producers cut some of Avery’s scenes. His exit from the film was imminent.

On the day Avery was fired from Lockdown, he was spotted smoking a sherm stick on the back of a grip truck during his lunch break while blasting music from a stolen boombox. (A sherm stick is a joint or cigarette dipped in the embalming fluid formaldehyde that elicits effects similar to PCP.) When asked to return the radio, Avery stormed the makeup room and lunged towards Mills. Chris, the towering tattoo artist, intercepted Avery, punching him in the face and splattering blood everywhere. Master P’s entourage then chased Avery off the set and toward the new prison facility down the road. Avery, who was in full wardrobe dressed as a prisoner, scaled a tall barbed-wire fence. Sirens blared. Guns were drawn. Avery had infiltrated a working prison. The film’s line producer, a former Navy SEAL demolition expert, had to plead with guards and snipers to stand down. Once subdued, Avery was ordered to leave the state of New Mexico.

Despite getting fired from Lockdown, Avery felt rejuvenated about his acting career upon returning to L.A. He went on auditions and even wrote a movie script titled G in a Bottle. “It was like [Kazaam], that movie where Shaq was a genie,” says Christine Chapman, an agent at Privilege Talent and Models, the Beverly Hills firm that represented Avery. “This kid finds a bottle and out comes this ex-gang member who changed his ways. It was actually kind of good.”

Avery befriended and eventually moved in with Chapman’s son, an aspiring model named Sean Spraker. After a night of partying, Avery crashed at the studio apartment of Spraker’s childhood friend, Jeremy McLaughlin, another Privileged client. For the next three months or so, he didn’t leave. “We couldn’t really do much about it,” Spraker says. “No one wanted to confront him.”

During this time, Avery landed his meatiest role to date as gangster G-Ride in the low-budget indie Shot. Roger Roth, the film’s writer and director, says he was blown away by Avery’s audition. Whereas most actors would’ve opted for big emotions during the scene he read, Avery underplayed it. Roth had found his G-Ride. His life would never be the same.

In Shot (originally titled Focus), G-Ride allows a White photographer named Robert, a stand-in for Roth, to ride with his gang and document life in the hood. In a way, Avery went method for the role. He asked Roth to address him as G-Ride and kept his prop gun tucked into his waistband. Avery was G-Ride at this point. Like the character, he was a gangster. He was also a chaperone for White tourists in the hood, like the roommates who tagged along to buy weed in the Jungle or Roth who filmed in South Central. The role came naturally to Avery, and it shows in his performance. “He’s one of the best actors I ever worked with,” Roth says. “He could nail every line. He could make you believe it. He could make you feel it.”

For the first time since Boyz, Avery was invested in a film. He wanted the final product to be real and true, and he protested when anything — a line of dialogue, a stitch of wardrobe — felt Hollywood. Roth went along with him. To get it right, he peppered Avery, now a technical advisor on the film, with questions about the hood and even his own past. “I asked him if he was ever involved in killing. He just gave a smirk,” Roth says. “I even thought it was kind of cool. It didn’t register, the heaviness of having to kill someone.”

The relationship between star and director came to mirror that of G-Ride and Robert. Avery bullied and intimidated Roth. On multiple occasions, he promised he would kill him. “I’m going to wait until your ass motherfucking thinks that I motherfucking forgot about it, motherfucker,” Avery would tell Roth. As for how he was going to kill him, Roth says, “I don’t repeat the threat. I don’t even tell the people closest to me. This way, I just know it died with him.”

Reflecting on his time with Avery, Roth is silent at first. He remembers sitting in his car, crying, paralyzed in fear, and the nights he spent sleeping in his secret editing suite. “Every hair on my arm is standing, and my entire face is numb,” he says. “I feel like he’s here right now. I’ve never felt that way before. … I believe in the afterlife, so that’s possible.”

He sounds out of breath. “When I think back on Lloyd, I think it’s one of the greatest missed opportunities,” Roth says. “Had he been able to control himself and not commit a double murder, there is no doubt he would have been a big success.”

Avery was arrested outside his grandmother’s home on December 8, 1999, following a tip from Spraker; the roommates fell out after Avery maced Spraker’s mother, Christine Chapman, during an argument at the Privileged offices. Avery was almost fatalistic about his arrest. As lost as he was at the time, he knew that prison offered him a chance to turn his life around, as it once did for Che. He found salvation in Dennis Clark’s congregation in L.A. County Jail.

Clark, the senior chaplain at the county jail, first noticed Avery in the front row during one of his services. Avery was eager to learn, and soon he was meeting the chaplain in his office for daily chats about God. Whenever Avery committed himself to something, he went all in. Religion was no different. “His faith was as real as any man’s faith I’ve ever known,” says Clark.

Avery carried his Bible into court each morning during his December 2000 trial, but from the prosecution’s opening statement, it was clear that this version of Lloyd Avery wasn’t being judged. It was The Blood Who Shot Ricky who was on trial. “What is this case about?” deputy district attorney Hoon Chun asked the jury. “You’ve heard the phrase art imitating life. Well, this is a case about life imitating, and even exceeding, art.”

There were holes in the case. The murder weapon was never recovered. All three eyewitnesses who identified Avery had credibility issues, including the star witness who had asked for money in exchange for testimony. Another eyewitness claimed that the shooter was 5’7” and dark-skinned, while Branch, the victim who died three weeks after the shooting, told police that Avery wasn’t the shooter. Police also accidentally destroyed shell casings from two shootings involving Avery from the spring of 1999 — a drive-by on Hillcrest Avenue and a shootout at the Islamic Center — that were said to match the ballistics from the murders. “It’s an embarrassment, certainly,” Judge Robert J. Perry said from the bench. “It is shoddy police work, unquestionably.”

Then Avery took the stand. He argued with Chun when the lawyer downplayed his popularity and offered a weak alibi for his location at the time of the murders. “Somewhere in Hollywood,” he testified. Avery was convicted on two counts of first-degree murder and sentenced to life in prison. He arrived at Pelican Bay in March 2001.

If Lloyd Avery is famous for one thing other than Boyz N the Hood, it’s that correctional officers took approximately 38 hours to find his body after he was murdered by his Satan-worshipping cellmate. To understand how something like this happens, consider that Avery’s death was the 18th homicide inside Pelican Bay as of 2005 since the prison opened in December 1989.

An Air Force Academy dropout serving life for raping and murdering his sister, Kevin Roby became Avery’s cellmate in August of 2005. Avery, a true evangelical, sensed an opportunity in their living arrangement. “I know God has him around me for a reason,” he wrote to Clark, the chaplain, in a letter dated August 29. “He knows very well that I am a devout Christian, and I pray for him to the Lord every day that he gives his life to God.”

According to documented reports, on the evening of Sunday, September 4, 2005, the spiritual dispute between Avery and Roby turned violent. “He was pushing his agenda to convert me to Christianity, which led to us fighting,” Roby told the Criminal Perspective podcast in 2020. The clash ended with Roby choking Avery unconscious, causing him to bleed into his lungs. He then placed Avery’s body in bed under the covers. Over the next day and a half, correctional officers made 11 counts of the inmates, including a standing count at 4:30 p.m. on Monday. Each time, Avery was tallied. Roby, meanwhile, ate double rations, wrote a flirtatious letter to one of Avery’s pen pals, and, if he’s to be believed, tied a string around Avery’s arm and tugged his limbs like a marionette to fool the correctional officers.

Shortly before the Tuesday noon count, Roby positioned Avery onto a pentagram he drew on the cell block floor. The walls were painted with Avery’s blood as part of a Satanic ritual that Roby intended as a warning to God. “He is next on the agenda once I accomplish what I want to accomplish in this realm,” Roby said during the podcast interview. Correctional officers handcuffed Roby and transferred Avery’s body to the infirmary, where he was administered CPR even though he was already decomposing. He was pronounced dead at 12:10 p.m.

Back in Los Angeles, Linda Avery had picked up her grandson from school when she received a letter in the mail from her eldest son. Minutes later, the prison called.

From the start, the family doubted the official account. Che Avery, who flew to Pelican Bay that evening, became suspicious upon viewing his brother’s body. It smelled like “old death” he thought. The family conducted a private autopsy, which slightly contradicted some of the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation’s findings. Whereas the CDCR listed aspiration of blood as Avery’s cause of death with blunt force trauma a contributing factor, the family’s autopsy stated that the cause of death was blunt force trauma complicated by aspiration of blood. It also described the injury to Avery’s skull, a 1.5-inch abrasion on his temple, as “suggestive of either a blow due to a flat surface such as a carpenter’s hammer or impact on a similar type surface.”

The reference to a carpenter’s hammer led the family to believe that maybe Roby didn’t act alone, but the blunt force trauma from that sort of weapon is in line with Roby banging Avery’s head on the stainless-steel sink in their cell. There is no evidence that correctional officers were involved with Avery’s death.

Believing a trial would bring new information to light, the family urged local authorities to file charges against Roby. But the Del Norte County district attorney refused, citing the fact that Roby, who confessed to the murder, was not eligible for the death penalty. The state attorney’s general then declined to supersede the local DA. A wrongful death lawsuit was also considered until the NAACP and Johnnie Cochran’s firm passed on representing the Avery family; coincidentally, Cochran once represented Lloyd Avery’s uncle, Dr. Herbert Avery, after the renowned obstetrician sued the Los Angeles Police Department for police brutality.

Meanwhile, the CDCR started two investigations under the supervision of the California Inspector General Office’s Bureau of Independent Review: one into Avery’s death and the other on the conduct of the correctional officers. Released in early 2007, the report found that the correctional officers failed to follow basic procedures such as removing Avery’s body before photographing the crime scene and, of course, for failing to notice that he was dead in his cell for 38 hours. Following an appeal, five officers received disciplinary actions ranging from a 5% pay cut for 45 days to a 10% pay cut for six months. When informed of the officer’s punishment, Linda Avery replied, “So they just got a little tap on the hand. Crazy.”

The correctional officer who discovered Avery’s body refused to comment. “I have nothing to say about it, man,” he said when I contacted him in November of 2020. “I’m retired. It’s no longer a part of my life.”

Another correctional officer with knowledge of the situation who asked not to be identified told me in 2007 that missed counts are not uncommon. “These [prisoners] are assholes. These aren’t nice people. So you’re trying to get your count done, and there is one person who refuses to stand. Are you going to count him?” he asked. “We like a quiet day. We cherish a quiet day. I know all these officers involved in this case. They didn’t do this on purpose. Was it lazy? Sure. Do they have absolute regret? Yes. To me, if there is any mystery here, it’s why was Roby taken from single-cell status to being in a double? Who cleared it? Prison officials don’t clear it. That’s management.”

In 2007, Pelican Bay officials declined to answer questions regarding the matter, citing “third party confidentiality and other individual privacy concerns.” Pelican Bay’s public information officer did not respond to questions sent last fall despite promising to do so by the start of 2021. Further attempts at communication have not been returned.

Che Avery moved to Augusta in 2008 in search of a fresh start. Instead, he found reminders of his past. “There are Crips and Bloods out here,” he says. “And they seriously think they’re Crips and Bloods and claim streets from L.A. There are guys out here from Hoover Crip. There are guys out here from Rollin’ 60s, so they say.”

When I reconnected with him in November of 2020, I asked about his brother’s legacy. Why has Lloyd Avery’s story resonated with so many people for so long? At first, he punted on answering, then he turned the question around on me. “Why did he have such an impact on you? Why are you so interested in the story?” he replied. “It’s a good story, bro.”

He kept talking and talking until returning to his brother’s demise. “He died in God’s favor,” he says. “That’s what this story is about.”

Che keeps some of his brother’s belongings in his garage. There’s the BMX bike Avery rode on the morning of his arrest and the Bible he studied in prison with its highlighted passages and notes scribbled in the margins. Che credits his big brother with bringing him closer to God, closer to believing in Jesus. Avery’s presence is felt in other ways, too.

Che’s youngest son is named Lloyd. “Looks just like him, too,” Che says. “It’s a good name. I didn’t want it to get lost. Wanted to hand it down.”

Comments

Leave a comment