In 1990, the Bomb Squad represented the crème de la crème of hip-hop sonics. The almighty production team behind Public Enemy crafted “Fight the Power,” the lead single for Spike Lee’s Oscar-nominated film Do the Right Thing, and provided the pulse for Ice Cube’s classic debut album, Amerikkka’s Most Wanted. The five-man unit was Teflon — until they put together a White rap group with one of the worst names a White group could have: Young Black Teenagers. “Black, to me, is a cultural thing,” said emcee Kamron, who appears in House Party 2 unironically sporting dreadlocks. “A state of mind, a state of awareness.” The blowback was palpable; hip-hop had tolerated White rappers like 3rd Bass, but YBT’s gimmick was a bridge too far.

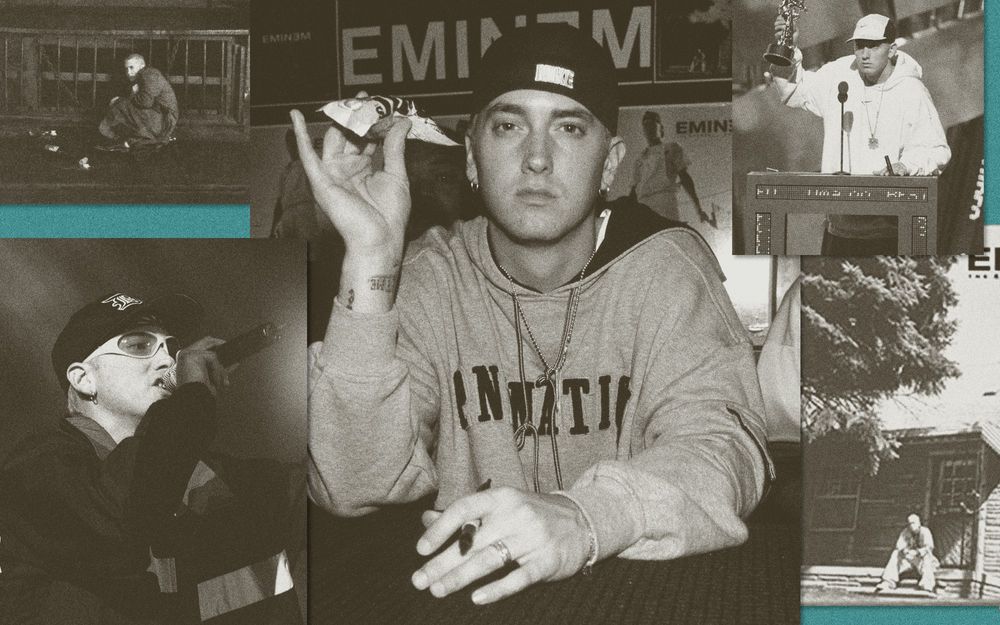

A decade later, the culture was fully grown. And where the Bomb Squad had slipped, Dr. Dre had soared — not just as a producer with a juggernaut label and two classics of his own, but by scoring the greatest album ever authored by a Caucasian rapper. In 2000, respect still eluded most White rappers, especially after punchlines like Vanilla Ice and Mark “Marky Mark” Wahlberg. Eminem and his second studio album, The Marshall Mathers LP, became the lyrically acclaimed, RIAA-certified diamond exception.

The album is a masterful confluence of punk, bluegrass, and subterranean hip-hop that gave life to a singular brand of Americana rap. It gave a voice to voiceless rap lovers who fancied Vicodin and lived in blue-collar cities where Black people were a rarity (think Columbine, Colorado). By the dawn of the aughts, Slim Shady had unearthed his own demographic.

“Before The Marshall Mathers LP, he was mostly shock rap and clever punchlines,” says film producer and director Erik Parker, former senior editor of The Source magazine. “His outrageous content was like a Trojan horse. With it came his artistic rise, along with a legion of White kids and ‘outsiders’ who were underserved by rap’s alpha personas.”

For music capitalists and rap fans of the Caucasian persuasion, Eminem represented the return of the Great White Hope. The rest of the culture wasn’t too happy about this configuration. After Eminem’s major-label debut, The Slim Shady LP, dropped in 1999, rap magazine XXL published a disrespectful illustration of the artist mooning the reader and an unauthorized cover story package titled “A Message to the White Man,” which included a faux Q&A based on quotes cobbled from various Eminem interviews.

And while The Source had given the Detroit spitter culture crowns like Unsigned Hype, Hip-Hop Quotable, and several covers, the mag deprived his albums of that elusive five-mic rating to denote classic material; The Marshall Mathers LP received only four. Twenty years later, Parker, who was music editor of The Source at the time of the album’s release, regrets the album’s rating. “It’s his best work by far,” he says today. “It lives up to all of the key elements that make a classic: overall impact, skill level, [and] historical significance.”

“Instead of just having that 1% fan base, it was the album that made Black people go, ‘Okay, he can really rap.’” — Bizarre of D12

Em responded to the slights as he would in a battle: He clapped back. On the album’s title track, he hit the “cheap-ass little magazine” XXL with a couple nasty combos. “Looking back on it, [provoking Eminem in XXL] was a mistake,” says Elliott Wilson, then editor in chief at XXL and current chief content officer at Tidal. “But it did lead to a classic moment.”

Two years after The Marshall Mathers LP dropped, rapper and Source co-owner Ray Benzino compared Eminem to Vanilla Ice, claiming that if Em were Black, he’d be no more successful than the less-heralded lyrical rapper Canibus. They traded diss records, one of which called Eminem “the rap David Duke.” Eminem severed ties with the magazine and squashed beef with XXL, posing for the latter publication in early 2003 alongside Dre and their newly signed breakout star, 50 Cent. “Personally, it changed my life,” says Wilson, who outsold The Source for the first time with that pivotal cover. “It validated everything I believed could happen.”

Those who tried to paint Marshall as a culture vulture failed to understand that Eminem was neither a Vanilla Ice nor a member of Young Black Teenagers. This pale horse to behold was a unicorn.

The gold is in the irony. In his early days, Eminem was to hip-hop what Black folks have been to America. He’s from the bottom — reared on the side of 8 Mile Road where poverty was life — and was raised by a culture that doggedly oppressed his talent, dreams, and purpose. Like brave Black men pre–Civil War, his calling to battle was met with mobbish resistance. When allowed to join predominantly Black ciphers, he was marginalized. Until he began rhyming, that is. “It was always a White Men Can’t Jump situation every open mic,” says Bizarre, Em’s childhood friend and fellow member of rap group D12. “Then, after the first 10 bars, they’d start changing their minds.”

What separated Eminem from most artists who sell 10 million copies of a single album is that he mined his diamond from the underground. Although he was already a multiplatinum Grammy winner, Marshall Mathers knew that Slim Shady wasn’t platinum in the streets. In order to attain that coveted respect, the White man had to jump over giants. Like Rocky Balboa returning to his original training quarters to beat the bigger, Blacker Clubber Lang, Em tapped back into his battle rapper roots and spent the album’s buildup stacking bars under the most luminous lights.

There were his phenomenal performances on Dr. Dre’s 2001 album. He rescued the Notorious B.I.G. underground gem “Dead Wrong” with the first four bars, then upstaged Redman on the The Nutty Professor II soundtrack. But perhaps Slim’s most outsized and underrated feat came on Funkmaster Flex and Big Kap’s 1999 platinum compilation, The Tunnel. Over a Rockwilder beat, the White boy blacked: “Hip-hop is universal now/It’s so commercial now/It’s like a circle full of circus clowns/Up in the circuit now/But now that White kids like it/They tell me that I can buy it/But as soon as I get on the mic it’s like the night gets silent/Either that or booed/So I keep an attitude.” On an album that featured heavyweight pens like Nas, Jay-Z, and Kool G Rap, Em came away with the standout verse.

“Because of [his race], he had to work harder,” says Atlantic Records A&R Riggs Morales, a former music editor at The Source and A&R at Em’s label Shady Records. “Like if you’re of color, you have to work harder than the White dudes at any company.”

“White people need to be made uncomfortable by White people — and Em did that. He made White people super uncomfortable with their truth.” — Mr. Porter (formerly of D12)

But if it’s peak Eminem you’re after, that only came with The Marshall Mathers LP. His best album was an amalgamation of masterful songwriting (“The Way I Am”) and Olympic lyricism (“Sick sick dreams/Of picnic scenes/Two kids, 16/With M16s/And 10 clips each/And them shits reach/Through six kids each”), baked under the genius of Dr. Dre. At the album’s equator are tracks like the rap-meets-yacht-rock concoction “Who Knew” and the 45 King–produced storytelling masterpiece “Stan,” on which Em brilliantly writes from the perspectives of an unstable fan and concerned superstar. The latter track landed a new term into the cultural lexicon.

“It all worked because we could see it was authentic,” Wilson says. “He really did have this messed-up childhood and tumultuous situation with his family.”

The Marshall Mathers LP delivered 27-year-old Marshall Bruce Mathers III the status he spent his entire life chasing: rap god. He tossed the styrofoam trophy inscribed “the greatest White rapper of all time” and entered legit top five MC discussions. If 2000 Jay-Z was Hova, Eminem was White Jesus. The wavy-haired Caucasian who hung over your grandma’s plastic couch was now nailed into your proverbial bedroom wall next to Nas and Wu-Tang Clan posters. “He went Larry Bird on that album,” Morales says. “It wasn’t even a color thing anymore.”

“It was his coming-of-age album,” Bizarre adds. “It was validating. Instead of just having that 1% fan base, it was the album that made Black people go, ‘Okay, he can really rap.’”

The Slim Shady persona was born from the late rapper Proof’s insistence that each D12 member create an alter ego. Aligning chart success with cosigns from rap purists and the greatest hip-hop producer to walk the planet allowed Eminem’s Mr. Hyde to grow hip-hop into one of the top music genres worldwide. It gave the antagonist a currency his skin promised but Detroit never paid: privilege. An American privilege that his darker peers did not possess.

Sure, Black rappers are allowed to lyrically smack and degrade Black women at their leisure. But Slim Shady owned the carte blanche to “rape sluts” and murder his ex-wife on compact disc. Imagine DMX penning a verse in which he slits a White woman’s throat and dumps her body, or Nas responding to Jay-Z’s diss track “Super Ugly” with a tale about killing his daughter’s mother.

“Em played by a different set of rules,” Parker says. “Rappers like Rakim, Jadakiss, or Jay-Z came from a space where being self-deprecating and overly playful with your words cost you the respect of your peers, social ranking in your hood, the approval of fans. Em was able to rise on a parallel track because he posed no threat to the alpha status. His authentic Whiteness allowed him to be free.”

While there aren’t many MCs who have been sued by their mothers for $10 million, raping your mom on wax remains harsh retaliation. Bizarre may claim those outlandish lyrics were justified (“His mom was certified crazy,” he says), but the apple didn’t fall far from the tree. Maybe that’s why Marshall was a moth to the flame of taboo. There are few topics more sensitive to the hip-hop community than homosexuality. For Eminem, it was a playground. In fact, The Marshall Mathers LP is his most homophobic output. Some variation of the word “faggot” appears 13 times across the album’s runtime, among other anti-gay slurs. The invitations to his penis are egregious. There’s a skit that depicts rival Detroit duo Insane Clown Posse fellating a fictional character named Ken Kaniff. Would Redman’s Doc’s Da Name 2000 go platinum with a similar interlude on its track list?

“We never thought a White MC could be that skillful and a superstar. He knocked all those doors down. Now the world doesn’t even look at Mac Miller in the context of, ‘Oh, he’s a White rapper.’” — Elliott Wilson

“It was a sign of the times, where the rawer you are, the iller you are,” Morales says. “A lot of stuff hasn’t aged well. Especially anything [homophobic].”

In 2001, the Journal of Criminal Justice and Pop Culture compared Em’s album to a study on misogyny in gangsta rap. Out of 490 songs released between 1987 and 1993, 22% contained lyrics articulating murder and various forms of assault toward women. The Marshall Mathers LP clocked in at 78%. It was permissible for Marshall to call Christina Aguilera a whore and Britney Spears a retarded bitch; to joke about impregnating J.Lo (Diddy’s girlfriend at the time) and send vitriolic middle fingers to teen-pop faves like NSYNC, Backstreet Boys, and Ricky Martin. (Who would say “fuck you” to Will Smith, of all people?) Whether multiplatinum, paraplegic, or deceased, no one had immunity from Eminem’s aim. Bizarre, who credits himself for inspiring Em’s shock-value style of rap, says, “When he started speaking like [actor] Christopher [Reeve] and talking about him being in a wheelchair, I thought he took it a little too far.”

The privilege The Marshall Mathers LP granted Em ran deeper than just crass shots at the famous and helpless. When his frat-boy trolling caught heat from gay activist groups (GLAAD), religious figures (James Dobson), vice presidential wives (Lynne Cheney), and the entire country of Canada, he became a sort of trailer-park Chuck D fighting the powers that be. He took aim at the very establishment that gave him his autonomy. When America’s biggest artist rubs his country’s nose in its own urine, it’s a big deal. When that artist is a natural brunette turned blond, it’s impossible to ignore.

“People forget how crazy the world was back then,” Wilson says. “We didn’t have social media, but he was really getting under people’s skin. People were really protesting him, and it was really shaking up America.”

Marshall not only took his arrows like Ali posing for Esquire, he also fired back with glee. He didn’t simply call out America, he mocked and berated it — laughed at the hypocritical accusations that his music fueled the fire within the country’s violent youth. He poked at the convenient overlooking of questionable and highly influential MTV programming or requests for censorship at the contradiction of the First Amendment. When parents wagged fingers of judgment, Em pointed back at their opioid bottles. And for all the misogyny criticism, a 2001 Teen magazine poll revealed that 74% of the girls surveyed would still date Marshall Mathers. Not even the Grammy board could resist him. “There’s no question about the repugnancy of many of his songs,” said Michael Greene, president of the National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences, in 2000. “But it’s a remarkable recording, and the dialogue that it’s already started is a good one.”

“White people need to be made uncomfortable by White people — and Em did that,” says producer and rapper Mr. Porter, also a former D12 member and a childhood friend of Marshall’s. “He put a spotlight on White America. He made White people super uncomfortable with their truth.”

Em’s upper-class status also gave him an artistic freedom not shared with the majority of rappers wrapped in melanin: He was able to simultaneously be a chart topper and spitter of labyrinths. That is the Venn diagram center every top MC aspires to hit. Slim struck the bull’s-eye with “The Real Slim Shady,” arguably the year’s most lyrical radio rap single. Twenty years ago, very few were climbing Billboard with verses as dexterous and intricate as Eminem’s.

“The album pushed boundaries on how far you can take super-lyrical rap,” says Morales, citing “The Way I Am,” the album’s second single. “Dude’s cadence and bars and perspective is aligned flawlessly.”

“C’mon,” Porter says. “You don’t know a rapper more technical.”

In 2000, the most remarkable lyricists were rhyme technicians like Ras Kass, Big Pun, and Pharaohe Monch. Pun needed R&B singers Joe and Donnell Jones to be competitive on the airwaves. Some proclaimed that Em’s pen was a doppelgänger of Monch’s, yet the Queens rapper didn’t receive radio love until his B-boy mosh pit classic “Simon Says.” Not even a symphonic collaboration with Dr. Dre (“Ghetto Fabulous”) could give Ras Kass a hit. The truth was, historically, rappers weren’t allowed to flow like a riptide and have their lead single go quadruple platinum. There’s a reason Kendrick Lamar paid Em homage throughout his career.

“Maybe his popularity is there because of his Whiteness,” Pharoahe Monch says. “But I think Eminem keeping lyricism as a conversation every time he releases a record still benefits Royce Da 5'9", Pharoahe Monch, Black Thought, and whoever else chooses to be lyrical.”

Although The Marshall Mathers LP sold 1.7 million hard copies its first week — setting a record that would remain until Adele broke it 15 years later — the album’s true significance is that it is Eminem’s magnum opus. Jay-Z had The Blueprint. Raekwon had Only Built 4 Cuban Linx…. Mobb Deep’s catalog truly begins with The Infamous. “This was the album that legitimized him with everyone,” Morales says. “If you had an issue [with his skills], it was gone now.”

For a snapshot of the album’s seismic influence, compare the pre–Marshall Mathers LP decade of White rappers like Everlast and MC Serch with the post-2000 landscape of Action Bronson, G-Eazy, and the late Mac Miller. By conceiving his own republic of rap, with a new demo to tow, Eminem homogenized the White rapper. “Here was a rapper who was truly breaking the color barrier,” Parker says.

“We never thought a White MC could be that skillful and a superstar,” says Wilson, who served as executive producer for VH1’s television show Ego Trip’s The (White) Rapper Show in 2007. “He knocked all those doors down. Now the world doesn’t even look at Mac Miller in the context of, ‘Oh, he’s a White rapper.’”

Eminem heard the message to the White man loud and clear. He’d heard it all his life. He listened to it throughout his climb onto rap’s Mount Rushmore. Jay-Z went on record saying (slightly inaccurately) that the only MCs selling major records in 2002 were Nelly, Em, and himself. It was a big reason why, the year prior, he entrusted Marshall to accentuate his very own magnum opus. Jay, uncharacteristically, repurposed a Royce Da 5'9" song that Em produced and obliterated lyrically and added it to The Blueprint. Some say the White boy bested Hov.

But that’s a whole other conversation.