“So, did you watch it?”

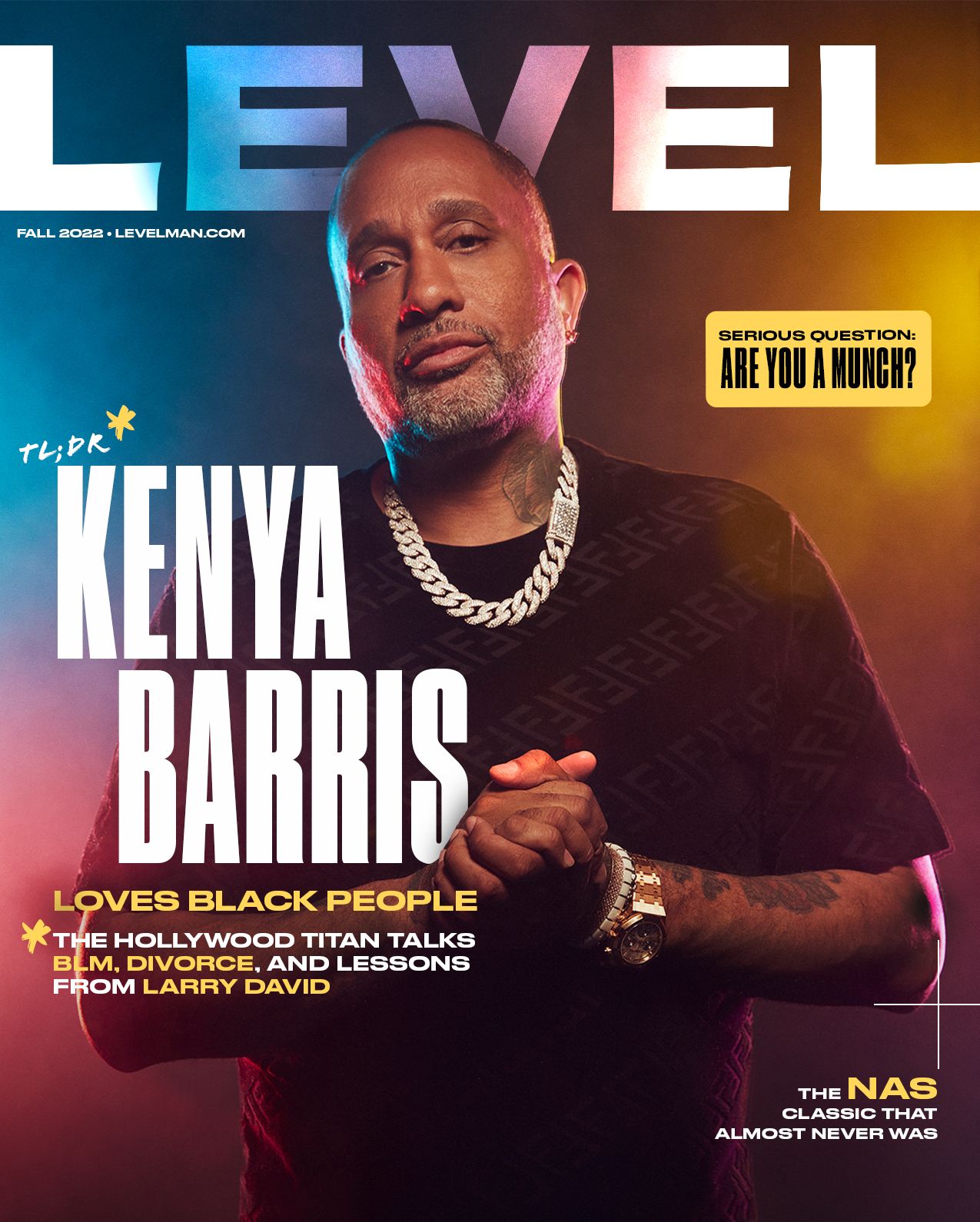

Kenya Barris, the man who created Black-ish and the many -ishes that followed, sits up in his seat.

“I did. Last night,” you reply, readying yourself for what you knew would come next.

“What did you think?”

He searches your eyes for clues.

“I enjoyed it.”

“Did you really enjoy it?”

Barris is folded into a cushy sofa in a plush hotel room overlooking Central Park. At the moment, he’s grilling you—no, pressing you. For thoughts. “Honesty.” Any criticism with which to bludgeon him. Some impression of his latest Netflix production, Entergalactic, an animated special created alongside Kid Cudi, who simultaneously released a soundtrack album of the same name.

“I’m a huge Kid Cudi fan,” says Barris, who serves as executive producer of the Fletcher Moules-directed “television event,” as it's been dubbed by Netflix. “It’s the first time an album and a show have kinda come out together. Each track on the album relates to a track on Entergalactic. And they converge in such an organic and symbiotic way, it takes you on an adventure that’s immersive. I want it to be a breakthrough moment.”

Entergalactic is living up to that expectation. To be sure, the love story here abounds with romance movie tropes—boy meets girl, loses girl, and gets girl back. But the animation adds a wisp of whimsy that uplifts the tale, and the music swells into the images. It’s a vibrant millennial cool, a vibe all the way through, with up-to-the-minute fresh characters voiced by the likes of Jessica Williams, Timothée Chalamet, Ty Dolla $ign, Jaden Smith, and Cudi, himself.

"There is something truly beautiful about the soul of Black folks. But I want to put us in a position where that soul speaks to everyone."

Barris, who saw this project to completion as one of the remaining shows from his dismissed Netflix deal (more on that later), is beaming with pride. Sorta. Despite his gut telling him he has a winner, he’s grown accustomed to taking criticism. He relishes in it. He’s a machine that filters bad words and negative thoughts into good stories, great shows. Barris has made it his trademark. So much so, he casted himself as a neurotic self-loathing Larry David type in his Netflix show BlackAF (more on that later, too). He admits he cares too much about critics and trolls who take aim at his work. You get the impression he has an addiction to disapproval. And it’s insatiable.

Today, Barris is looking to spread the word about his new show that “he can’t help but love” but feels tortured for succumbing to his optimism. Therefore, he needs negative input for balance. Some grounding. The voices cannot find him here, 40 some-odd stories in the sky, so he seeks them out.

“I expected not to like it,” you say. “The animation took a moment to get fully lost in.”

“Oh man, I felt the same way about [Spider-Man: Into the] Spider-Verse,” he responds. “I went to the premier of Spider-Verse and I was like, I don’t know, this feels a little janky. Then I watched it again and again. And I realized they broke convention.”

Entergalactic is just one of many projects Barris is helming these days. He recently untangled himself from a $100 million production deal with Netflix in favor of a position as principal of BET Studios, a production entity under the Viacom umbrella. Residual projects from his Netflix deal include You People—an inevitable 2023 blockbuster starring Eddie Murphy—and a comedy series with Vince Staples. Barris also has a reimagining of The Wizard of Oz on deck, as well as forthcoming TV shows with 50 Cent, Fat Joe, and Snoop Dogg set for different platforms. A lot going on, indeed.

On the personal front, his on-again-off-again divorce is on again and playing out in the public eye for everyone, including his six children, to see. All the while, he’s contemplating a revival of BlackAF, which divided audiences along the lines of brilliant and bull-ish. Plenty of hand-wringing ahead for Barris. Which means lots of great art on deck for us all.

—

—

LEVEL: You had a Netflix deal worth $100 million. And you decided to leave the company somewhere in the middle. Why?

Kenya Barris: Ownership. Viacom gave me an opportunity to have ownership and equity in the studio we created. I learned a long time ago that if you can help it, buy something instead of paying rent. I wanted to bet on myself. Tyler [Perry] is one of my mentors and brother—I learned a lot from him and Oprah [Winfrey]. When Oprah bought Harpo and started buying her own production studios, that changed everything. Having our own equity stake. Scaling a legacy that you can build from. The only way to do that is to have some sort of ownership.

How did you end up at BET Studios? Seems like Black audiences tend to have a complicated relationship with the network.

I did not want to call it BET Studios. It’s Viacom. Scott Mills, president of BET who has become my brother, was like, You need to look at the brand equity of this. I was like, I don’t know man, we’ll have to fight an uphill battle. And he showed me, of all the Viacom networks, it’s by far the most successful, other than CBS. We perceive something different but their viewership, their numbers, their profitability is by far ahead. It’s like the underdog story. I’m like, if we can get in there and change the narrative, we can make the studio something where people want to come. Sometimes that’s the opportunity you look for. You know how they say: Buy low, sell high.

Seems like you’re embracing the role of the Black writer who tells Black stories.

I always have. I started off quote-unquote in the chitlin circuit of shows: the UPNs, the CWs. I saw how those shows aren’t necessarily respected and how some of those writers, producers, and directors were just as talented—if not more—than others. So it was very important for me to help change that narrative. And I’m still a populist; I want to be mainstream. But I want to be mainstream in a sense where I’m not running from who I am and what we are. There is something truly beautiful about the soul of Black folks. But I want to put us in a position where that soul speaks to everyone. And the only way to do that is to put yourself in a position to speak in a way everyone can see themselves in your story and you allow your story to be a part of everyone else’s story.

I was thinking of the story you once told about getting the “Black call” from big names in Hollywood. The kind of call where you get to only talk to them about Black stories.

At first, I was pissed. Then I started realizing this is the right call. It is my job to take this and do it at the same level as [Martin] Scorsese. I think Spike Lee did that. He is arguably at his peak, one of the greatest filmmakers in the world. He told our stories but he did it at such a level of auteurship, everyone could relate to it.

I read a quote where you said, If you don’t do business with me, “I’m not gonna say that you’re racist, but other people might.” I know you were joking, but it seems like there’s a hint of reality to that. How do you leverage race in your career?

That was a joke. But I absolutely leverage race. Leverage is what makes the world go round. I leverage it in a way where I feel like I don’t wield it. I don’t make it where people feel like it is a toxic crutch. I do it in a way where I want people to truly hear the stories we’re telling.

" You don’t want something everybody likes; that’s just vanilla ice cream. I want banana nut. Maybe not for everybody, but the people who like it, love it."

+

Let’s go back to your work with Netflix. You say you left because you wanted equity and to tell certain types of stories. Were there stories you wanted to tell at Netflix that you couldn’t?

They didn’t stop me from doing anything. What I saw was I couldn’t control the audience and the algorithm the way I’d like to have been able to. Netflix is very impartial that way. They let the numbers determine what’s going on. I would go back to Netflix tomorrow in terms of my friendships, the people I worked with. I have a huge movie with Jonah Hill and Eddie Murphy coming out that they gave me unbelievable reign that no one else would have done. I have other documentaries I’m doing with Netflix. I still feel like they are part of my family. And [Netflix CEO] Ted [Sarandos] did not have to let me out of my deal. He did and he continued to do work with me. When he saw the equity part, he was like, I’m not gonna fight you on that.

BlackAF was one of your first shows under your Netflix deal. As a novice actor, you star as a contemptible version of yourself. Did that level of visibility change your life or the way you move?

It was the hardest thing I’ve ever done. But the one thing that makes me fearful of doing it again is that loss of anonymity. I had lost some anonymity because there are not a lot of Black writers at my level, so some people recognize me. But now I’ll be in the store—I still go to the store wherever—and people will be looking. And I’ll be like, Why is this nigga looking at me. “What’s up bro?!” I’m still from the hood. And then I realize and I’m like, “Oh, heyyy.”

How did you make the decision to come from behind the camera?

I was a huge Curb Your Enthusiasm fan. Larry [David, creator of Curb] stepped out from behind the scenes to do that. I spoke to him before I did BlackAF and he gave me some amazing advice. He told me I should do it. We had a great actor set to play the role, but he said you should do it—there are some things that only you can say. He said when you’re auditioning people, make that your rehearsals. I think he’s a genius.

Episode five of BlackAF was special. That’s the one in which Tyler Perry gives you advice to tune out the critics, and you grapple with the idea of honestly evaluating Black art. After that, it seems the series took a turn.

That episode had its own Twitter feed. Interesting fact: At the time, that episode was the most-tweeted-about comedy in Twitter history. That’s when I realized you don’t want something everybody likes; that’s just vanilla ice cream. I want banana nut. Maybe not for everybody, but the people who like it, love it.

BlackAF was greenlit for a second season before you left Netflix. Where is it now?

I was just in Atlanta doing a movie with Snoop. I was followed in the mall like Ruben Studdard after winning American Idol. I was shocked at how many people watched and loved it. We were preparing to do another season before I left Netflix. I would love to do another season. [Co-star] Rashida [Jones] would love to do another season. Maybe it will happen. Ted greenlit BlackAF movies. But everything starts to become this sort of conversion between commerce and art. That’s the key.

"I grew up with a lot of fear. Fear is my base. And that fear drives me in some aspects to be successful. I’m so worried about failing that I double dot my I’s and double cross my T’s."

+

As a kid, what was your dream?

I started off wanting to be a marine biologist, like every other little kid. Wanted to float around and see whales and shit. I was pretty good in science and math. Then I remember going to the doctor. Something about going to the doctor and not feeling good and that dude making you feel better. I had a little brother that passed with leukemia. I saw the pain it caused my family.

How old were you when your brother passed?

I was 4. It made my mom more protective. I was the last kid on the block to cross the street by myself. My friends would make fun of me like, Ah, you can’t cross the street. Of course because of who my mom is, the moment she starts letting me do it, two weeks later a kid gets hit by a car. She’s like, I’m back to walking you across the street. I think it caused her a lot of fear. If I get on a plane now and say, Mom I’m going to Europe, she doesn’t ask what I’m doing in Europe. She says, I hope that plane is okay. I’m like, I do too, Mom! Do you not care why I’m going? [Laughs] It creates this dark cloud because there’s nothing like burying your child. There’s no pain to compare to that.

So I grew up with a lot of fear. Fear is my base. And that fear drives me in some aspects to be successful. Because I’m so worried about failing that I double dot my I’s and double cross my T’s. Some people are led by confidence and manifestations; I’m led by This is not gonna work. That part of me makes me feel like I have to go extra hard to do all I can. You can do all you can and it still not work, but I’m driven by the fear of failure.

Aside from how his passing shaped you, do you actually remember anything about your brother?

Not really. Yes and no. It’s a constant memory in my family. Pictures. I remember the pain it caused my mom. He passed in my mom’s bed. He was like 3 and a half. He lived way longer than he was supposed to. If he had it today, he would have lived.

It breaks your heart to see kids struggle with illness like this, but it is so much better today.

My best friend, like my brother, has a son who is dealing with leukemia. He turned 1 in the hospital, was 11 months old when they found out. It came out of nowhere. He’s going through his second round. He’s technically in remission, but it has caused me to break down sometimes and challenged him and made me see the true grit of who he is. At the same time, I embrace the medicine. Seeing my boy and what he’s going through and seeing my young G that is my hero, I feel like there are amazing advances in medication. People are homeopathic and vegan, and I’m like, Yeah, but sometimes medicine works, too, bro! [Laugh].

Can we talk about the recent headlines outside of your new deal? Your divorce is playing out once again in public. Does that affect your work?

I hate it. It’s not fair. Fifty-two percent of all marriages end in divorce. The idea that there are not a lot of Black [screen]writers means my kids have to read about mine. She’s an amazing woman. I have nothing but love for her, but more importantly, I have nothing but love for the world we were able to build together. But it makes me feel for people who are going into relationships because it’s the hardest thing in the world. That’s the hardest part about losing anonymity. Those types of things that are private play out in the public eye.

Your parents got divorced when you were 5 years old. How did that affect your life?

I think it made me stronger. I also feel like it made me want to keep my family together in a way I don’t think I had. It continues to have an impact on my life.

When it comes to impact, how did Black Lives Matter protests and the Ahmaud Arbrey and George Floyd killings affect what you write and what we see on TV?

I think that it goes back to Emmett Till in a lot of ways. His mom was the hero. Her leaving that casket open with her son changed the civil rights movement. It doesn’t matter who you were or what was going on; when you look at what people did to a boy—a child—the humanity within you kicked in. When you see tapings of the killing of Ahmaud Arbrey, the taping of the life being sucked out of George Floyd by people who were supposed to protect and serve him, that challenges your humanity no matter what their [skin] color.

"When I saw one of my kids’ 23andMe, I was like, You can’t let this out. Let’s tear this up... I have a show called Black-ish."

+

What did it do to you?

It really affected me. [Civil rights attorney] Ben Crump has become a friend and a brother. That whole summer, you were worried. I’m like, are we ignoring that we’re at that point where it’s about to kick off and shit’s about to be different forever? It scared me and angered me. It was something I definitely feel needed everyone.

I remember seeing white folks protesting in the streets, shouting Black Lives Matter. It touched me in a way that I did not expect.

My white friends started getting their 23andMe [genetic test] results and saying, “Two percent—I’m one of the good ones, my brother!” [Laugh]. People wanted to come together. We are truly a melting pot. When I saw one of my kids’ 23andMe, I was like, You can’t let this out. Let’s tear this up.

Too white?

Yeah [Laugh]. I was like, we can’t let this get out. I have a show called Black-ish. Their moms is bi-racial, obviously. I was like, How did this happen to you? But I feel like we’re all a blend.

DNA tests became popular and changed the way people view race. Now it seems there’s a narrative that being Black-identified is race—but also culture.

It’s secular in some aspects. I look at your experiences in the world. Like, Fat Joe—he’s my brother. He gets to drop the N-bomb because he’s Afro Latino. At the same time, 20 years ago, depending on where he grew up, that would be a different thing. I always look at it like, if we get pulled over, are you gonna get in the same trouble as me? If you are, then we’re in the same group.

Speaking of Fat Joe, let’s talk about your music ambitions. Aside from BET Studios, you’ve quietly signed a label deal for Khalabo Music with Interscope. Did you always think you were going to do music at this level?

I did not. I do love it. It’s out of my depth and it takes a huge amount of skill. I have an ear. I like listening to music and doing it, but it is a venue that I have not quite mastered. We have some amazing artists: GoGo Morrow and Rocco. We’re doing soundtracks and other things. We’ve been successful, but at the same time, it’s something I want to learn.

You’re developing several TV shows or movies with rappers now. Do you plan to do any other projects like Entergalactic, where their music informs the narrative in a creative way?

We don’t have any plans but I want to continue this, whether it’s season two of Entergalactic or we create a piece of [intellectual property] that could translate to other artists. I would love that. That is the IP that we’re looking to create, whether it’s the next season of this, or we do Kendrick [Lamar]’s next album, or we do Justin Timberlake’s next album and create a narrative around it. Animation and music blend together in an amazing way.

This approach tends to give context to the music. Similar to how Prince did with Purple Rain.

One-hundred percent. Lena Dunham, we are not friends. We have our shit. [But] the way they used music [on Girls] and the way she told her story and let her voice come across, I loved it. Made me think I don’t know what it’s like to be a NYC semi-socialite, entitled, young white girl, but I got that show. She used the music and made it all aggregate into something that I was able to follow her story. And I don’t fuck with her. [Laugh]

Have you seen a real change in the way we see representation over the years?

I see Netflix doing things like Strong Black Lead. I see HBO and their programming. I see everybody trying to take a shot. Everyone wants to see themselves reflected. I don’t care if you’re skinny, fat, Black, white, Asian, Brown, old—you want to see some reflection of yourself. Black people in a lot of ways are the heartbeat of this country; look at fashion, music, sports. The idea that we’ve been free less time than when we were imprisoned, and look where we have come. That takes a certain spirit. And I think that spirit becomes the blood that flows through this country. When we’re at our best, we are looking at our immigrants and our niche, imprisoned populations, and our newly found Americans. We’re looking at people who have something to prove and are trying to go up that ladder. And that’s what our country is built on.