I’m on the corner of 23rd Street and Sixth Avenue in Manhattan. There is a disheveled man pacing in front of me. He has gray hair on his forearms that’s set against brown skin with red undertones. I see the stub of a cigarette clinging to his cracked lips. He’s having an intense conversation with himself.

I’m waiting for a friend, but she’s late. I find myself looking for my father in the creases of this man pacing and mumbling.

Like him, my dad is homeless too.

And as dementia grabs hold, wherever he is right now, he’s likely talking to himself as well. Is someone staring at him, wondering if he has a family or a place to stay? He has a family. But not a place to stay.

My friend jolts me from deep thought.

“Hey! You okay?”

I’m not okay.

Last year, my uncle told me my father was homeless. I hadn’t seen him in 20 years. I can count on one hand how many times I’ve seen him since I was a child. I immediately decided I was not going to help. Why should I? Why should I fight for the life that created mine? He never fought for me.

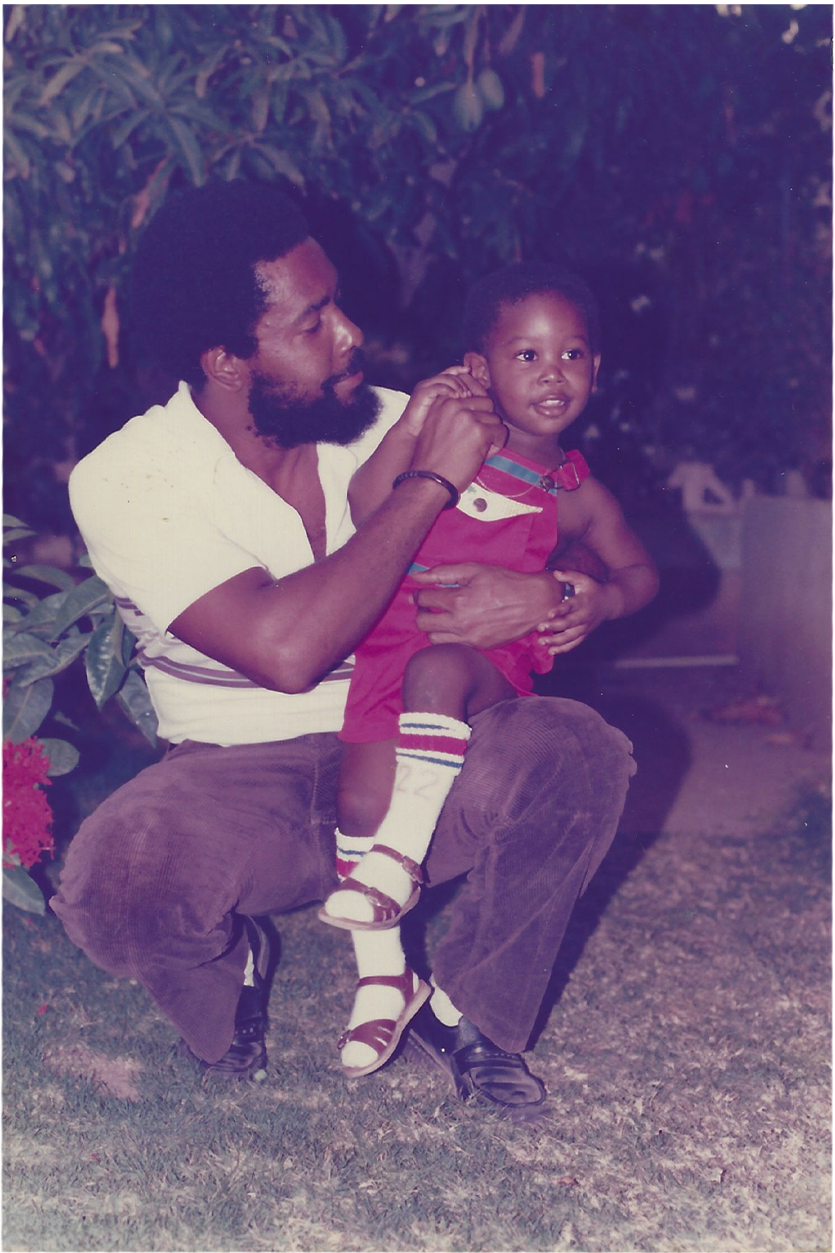

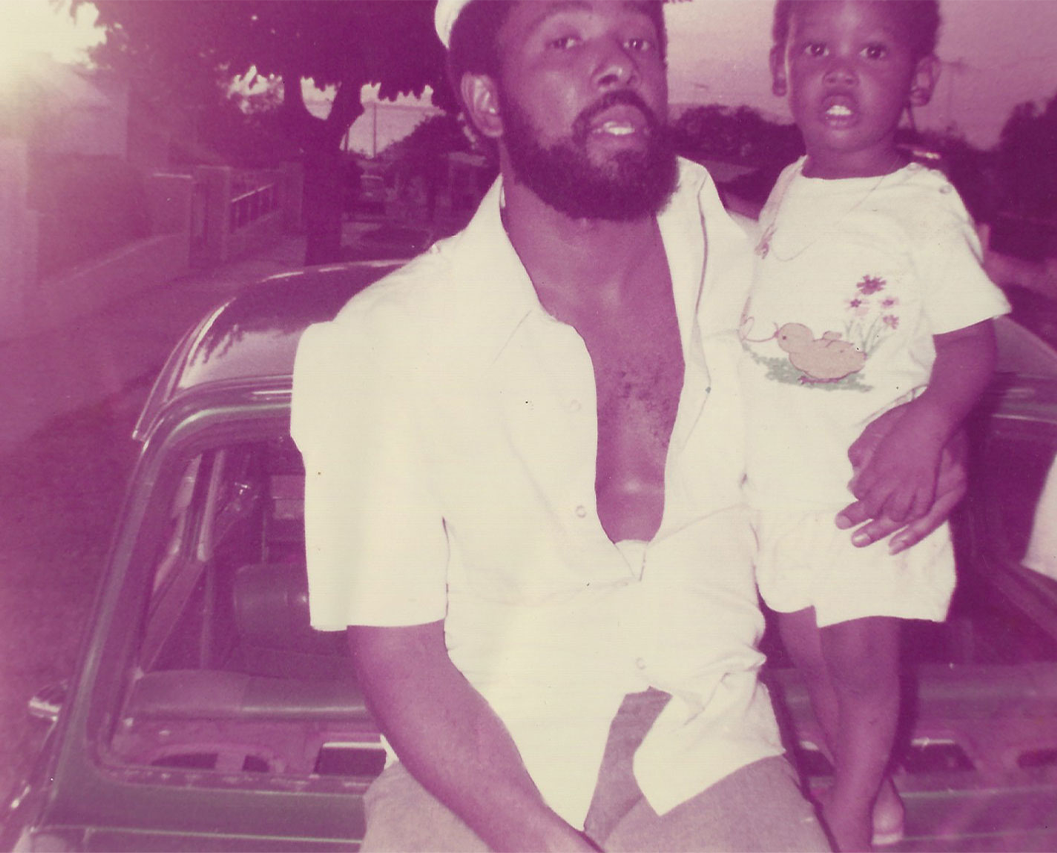

My mother and I moved to New York from Jamaica in 1985. My dad stayed in Jamaica and came and went as he pleased, sometimes popping up with no announcement. I did spend one summer with him in Miami when I was in elementary school. He spent the entire time criticizing everything from the way I walked to the way I sprinkled salt on avocados. When he was around, he expected me to eat what he ate, adjust to his ways, excuse years of his absence, and then resume one-sided debates about his outdated politics.

I’ve cried to my mom about my dad. Once, I asked her why she chose to mate with him of all people. It was a cruel thing to say, but she allowed me to lash out.

I’ve cried to my mom about my dad. Why was he so hypercritical? Why was he such a failure as a father? Once, I even asked her why she chose to mate with him of all people. It was a cruel thing to say, but she allowed me to lash out.

And yet, I still keep track of him. I usually know where he is and how he is doing in general. But then, his phone number began to change often. Last year, he was staying at a community center where he tended the garden in exchange for a thin mat to sleep on. I called a few times to check on him, but then one day, a manager, in her heavy Jamaican accent, snapped at me through the phone.

“Don hasn’t been here in quite some time,” she said. “But you know how him stay. He likes to go his own way, and once him make up him mind, you can’t tell him nuttin.”

They had no current information for him, no forwarding address, and no general concern that he had vanished.

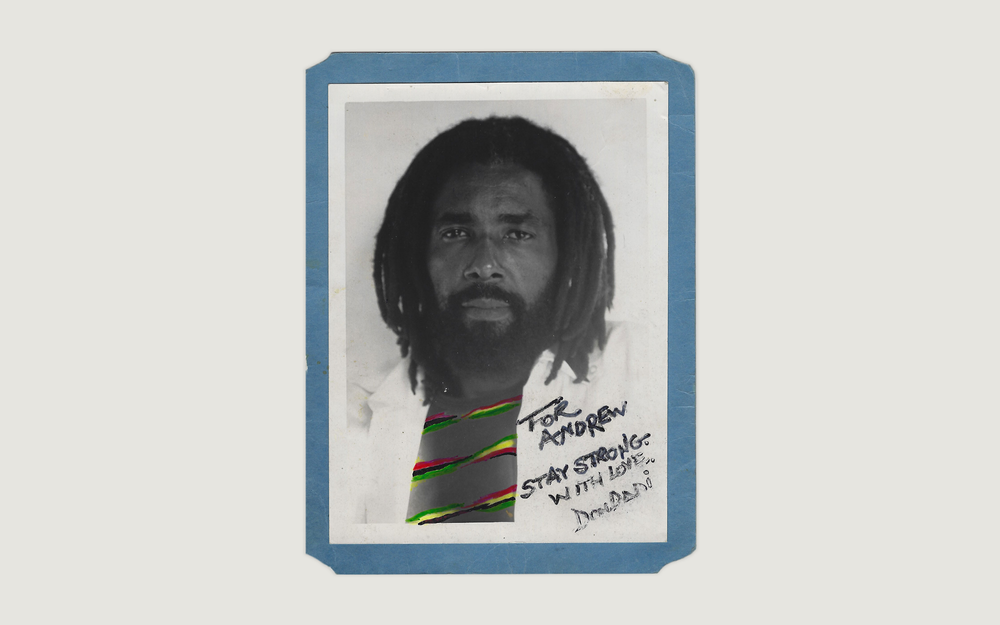

My father is a Rasta, built on honor he can’t uphold. I am a writer, ambling through ideas I don’t always grasp. He roams an empty castle of beliefs, shouting at residents who’ve long since left. I travel an aimless path, cursed with self-doubt.

“Ah mad him mad,” they might say.

He must be crazy.

I asked my mom once what my dad did for a living. My mother told me he was a “freelancer,” uttering it like a slur.

My father has always found it hard to keep jobs. I’m not sure how many jobs he’s had, but he refuses to engage with government agencies like Social Security and the Internal Revenue Service or even labor unions. So it’s been hard for him to find jobs that don’t go against his principles.

He’s long been an activist, particularly working to preserve the legacy of Marcus Garvey. But to him, all money is dirty. He’d rather do odd jobs like gardening, reading, and the occasional lecture on civil rights.

[My father] moved in with his mother, an infirm woman who never expected to house her grown son. He repaid her generosity by committing Social Security fraud to collect what little resources she had left.

If I ask him why he doesn’t keep a job or have any money, his answer is simple: “Who you tink say you a deal wid, boy? I am not anyone’s slave.”

Eventually, as one grows older, how you live your life begins to catch up. When you don’t build familial ties, there is no one to care for you when it’s time.

At one time, my father stayed at his dying sister’s place, falling out with her after he quit the upkeep of her garden. It was the only thing she’d asked of him. He then moved in with his mother, an infirm woman who never expected to house her grown son. He repaid her generosity by committing Social Security fraud to collect what little resources she had left.

My uncle, my dad’s brother, called to tell me this. I am more ashamed of my dad than surprised by his actions.

For the last several months, I still see my dad’s message alerts on WhatsApp. He sends chain letters and YouTube clips about Marcus Garvey and the Transatlantic and whatever else sails through his jumble of thoughts. That’s how I know he’s alive. And that he has Wi-Fi. And libraries.

Last week, I called my father.

“Why are you always changing your number?” I asked.

“So I guess is I report to you, now, Mr. Big Man, eh? You ah live New York so you tu’n Wall Street for the dough, haha,” he snapped back.

I closed the app, the only way I can find him. Then I deleted it. Then I downloaded it again after 30 minutes of cursing him.

My father has four children by three mothers. Aside from an occasional email rally, years apart, none of us speaks to him or to each other. The cornerstone of our correspondence has broken our hearts again and again.

We’ve braved his insults that we were too fat or too rich or too spoiled by our mothers, the ones he left behind to raise us alone. We battled his dogma, like railing against the medical industry as my older brother and sister finished medical school or bashing prep schools when he learned I’d gotten into one.

Wrestling with the resentment of a toxic parent is all-consuming.

Sometimes, I drift into another future. I go to Miami. In the vision, I catch the quickest flight, book a room, travel the streets with my phone and portable charger. In the fantasy, I find my father in public, safe, sitting on a bench. Or he’s laying in shady grass. He sees me but won’t move. I need to coax him out of a stupor or prop him on my body. I need to treat him better than he’s ever treated me. So I do it out of spite.

I want to forgive him for his failures. But I can’t even forgive myself for resenting his absence. So I watch his messages bubble up twice a week, hoping that one day the screen goes dark on us both.