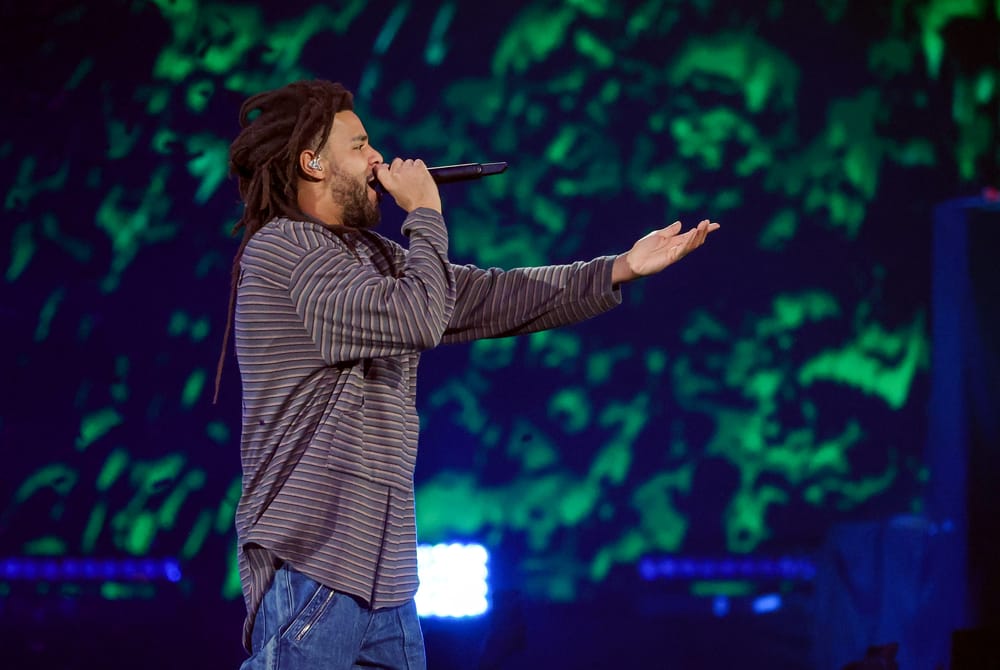

Where were you when J. Cole ended what could’ve been one of hip-hop’s most entertaining battles before it really got going?

On Sunday night, in the closing performance of his Dreamville Festival in Raleigh, N.C., Cole expressed regret for releasing his song “7 Minute Drill,” a lukewarm diss track that responded to Kendrick Lamar’s inflammatory verse on Future and Metro Boomin’s No. 1 hit, “Like That.” Of course, that cameo was a response to Drake’s 2023 track “First Person Shooter,” on which guest star Cole name-drops Lamar as one of the “hardest” three MCs, along with himself and Drizzy: “We the big three, like we started a league/But right now, I feel like Muhammed Ali.” K Dot didn’t appreciate that, apparently. “Muthaf**k the big three/N*gga, it’s just big me!” he shot back on “Like That.”

Drake has yet to respond, save for some indirect onstage rants. Very par for the course. But last Friday, J. Cole dropped a surprise project, Might Delete Later, defending himself with a “warning shot” that criticized Kendrick’s catalogs, amongst other light jabs. Receiving mixed reviews, Cole went to do something unheard of at his Dreamville Festival: He apologized to his longtime friend, Kendrick. Not only did he apologize, he called his response “the lamest f**king s**t I've ever done in my f**king life,” adding that he took no personal offense to “Like That” but “the world wanted to see blood.”

Hip-hop fans responded accordingly. Jokes were made. Memes were generated. Melodramatic vows to boycott Cole’s music were promised. In the midst of a severe backlash, a few fans and commentators had his back (Charlamagne tha God being a notable example). I agree with the radio host: While many perceived Cole’s move as an act of cowardice and fear, I saw someone who got peer pressured into doing the most over the least (Kendrick’s smoke was primarily directed at his longtime nemesis, Drake). I saw a bravery to go against expectations of hip-hop and masculinity—and accept whatever repercussions came with that bold move. I saw Cole's comparison to Muhammad Ali going beyond an empty punchline and beginning to feel true in more than one way.

I wanted to see a battle just as badly as anyone else. But J. Cole’s apology makes me wonder: What if we started doing this more? How much better would it be if we didn’t take everything to heart and let some stuff slide?

Who amongst us haven’t been pulled down by the weight of other men’s expectations? It’s certainly not Cole’s first time (“My lowest moments came from trying too hard/To impress some n*ggas that couldn't care if I'm on,” he rhymes on his 2016 track “False Prophets”). The popular animated series The Boondocks coined the term “n*gga moment,” describing it as “the perpetual conflict between n*ggas over trivial or ignorant things,” also warning that “every Black man’s spirit is weakened in a n*gga moment.” Cole had such a moment in the midst of chatter around Kendrick’s fiery “Like That” verse. He expressed that sentiment on stage, describing how disturbing it felt, how he was unable to sleep soundly. That action—releasing a petty diss track that even he didn’t believe in—just wasn’t him, at least not anymore. When you’ve spent years attempting to find yourself, you reject anything that misaligns you.

Related: How J. Cole Made Up for Drake's 'For All the Dogs' No-Show

I wanted to see a battle just as badly as anyone else. But J. Cole’s apology makes me wonder: What if we started doing this more? How much better would it be if we didn’t take everything to heart and let some stuff slide? What if we could just not react to everything? How dope would it be if when we got a little beside ourselves, we could recognize it, take accountability, and apologize? Wouldn’t that be better, not just for hip-hop but for our culture and society as a whole? Instead, we stand 10 toes down in immaturity and wrongness. We’re men. We’re hard, not soft. We don’t apologize.

Jermaine Cole is a conscientious objector to unnecessary drama. He is refusing to go to war. He is dodging the draft, and he will take an L but also come back fortified in his purpose. When Ali refused to fight in Vietnam, he said, “The Vietcongs ain’t calling me n*gger. I don’t have any problem with them.” At some point in personal transformation, you realize there are bigger events at play, that there are more important things to worry about, and that, frankly, some s**t just ain’t that serious.

It was Black manhood that told him to respond to something insignificant with aggression. Yes. That is the lamest s**t.

The unanimous critique Cole's backing down is his recent practice of calling himself the best rapper out, and challenging anyone who feels differently. In fact, in an interlude on his latest project, a young lady references that he’s on his “greatest rapper run.” As a writer, former aspiring MC, high school lunch table battler, and lifelong lover of hip-hop, I felt that there was a way to approach this. He could have penned something calm and honest while scathing, as he did with “False Prophets” towards Kanye and Wale (allegedly). But why would he? He loves and respects Kendrick. Simply put, he didn’t want to. And the other reason is that he couldn’t.

In his camaraderie with and admiration of K Dot, a lengthy, eloquent, surgical critical analysis of the artistry and personality of Kendrick wouldn’t make sense because he wouldn’t believe it. One of the most glaring aspects of “7 Minute Drill” is how contrived and uninspired it sounds. It seems like he compiled K Dot comment section criticism and created the most lackluster miss track I’ve ever heard. I can’t fully fault him because it wasn’t him, and he admits that on stage. It was his boys blowing up his phone, looking for “a toxic reply.” It was social media and hip-hop pundits. It was Black manhood that told him to respond to something insignificant with aggression.

Yes. That is the lamest s**t.

Much of the backlash Cole is receiving is rooted in the fact he’s forcing us to subconsciously recognize that much of what we embrace and celebrate in hip-hop, Black masculinity, and how we interact with one another is, in fact, lame. Many of us aren’t at a place of peace or maturity to let trivial things slide. Half of us couldn’t ignore a snarky comment on Instagram without a vicious clapback or arrogant condescension. The entire thing would have been unnecessary and a gross waste of time.

Jermaine stands in on the shaky opposing duality of his artistry as a hip-hop giant and his humanness. Hip-hop's definition of greatness still rests in bloodthirsty domination and invisible crowns. But in his humanity, he’s on an existential quest for purpose. Yes, battling is one aspect that separates this musical artform from others. This is hip-hop. But does it have to be?

Within all artforms, there is comparison; therefore, there is competition—whether from the public or artists themselves. Within all sports, there is competition and the pursuit of being the best, the champion. Within all combat is inherent brutality and aggression, with the most deadly being war. But hip-hop finds itself in a precarious position. Being identified as art, culture, sport, and battle, the lines have increasingly blurred, leaving discernment difficult, if not impossible. This is the only art and culture where this form of clash is requisite. Although this element may make it unique, exciting, and drive creativity, it can also be argued that it arrests the development of the music, the figures involved, and the culture as a whole.

Related: Here's What I Learned From Playing Professional Basketball With J. Cole

That’s where we find Mr. Cole, and Black men at large: stuck, struggling to hopscotch the numbered chalk boxes of ourselves, not knowing whether to be an artist, an adult, or a warrior. Not all competition is combat, and not all combat is war. A scorched earth ideology leaves zero room for hip-hop or Black men to grow, and the man on that stage has been on a journey of growth for the past decade.

We’ve seen his aesthetic change from the young rapper starter kit to a man in search of himself. Gone is the flashy jewelry he raps about in “Chaining Day” and loud designer threads that were once his go-to. You’re much more likely to spot him peddling a bike than pushing a luxury vehicle (although he’s reportedly got those in his garage, too).

Much like Cassius Clay became Muhammad Ali, Cole began the process of becoming the person he is today: a man who had a lapse in character, a breach of his values and integrity. This is a man who desperately wanted to clear his conscience to continue on his God-appointed path.

So much of the frustration from hip-hop figures like Joe Budden and the broader community was rooted in the fact that this action is “not hip-hop.” They may have commended him for his maturity but not his identity as a hip-hop artist, which, although I understand the notion, makes me believe that these two ideals are separate—being hip-hop and being a mature man. Although we spent all of 2023 celebrating hip-hop’s 50th birthday, the concept of maturation is still murky, at best.

What makes us discuss Ali over Tyson or Mayweather is the fact that he stood for something. He wasn’t just a warrior, didn’t have a perfect record, didn’t make the most money. But he had a purpose, a cause, and integrity. He wasn’t just a great fighter and champion. He was a great man, and that’s what Cole is chasing.

Two years ago, on Kevin Durant’s podcast The Etcs, Cole spoke of changing his combative mentality to one of collaboration. “The competition part, I’ve stripped away and now I'm more interested in the relationship,” he said, speaking on Drake and Kendrick Lamar. “I don’t want to be like, we never kicked it. We never really did nothing.” He discussed respect, competition, and, most importantly, life after music. He realizes the people who will be able to best relate to him are those who were his greatest competitors, and risking those connections because he made them rivals and not friends seemed ridiculous. He said he wanted to look at things more through the lens of wisdom because “n*ggas is gettin’ old, bruh.”

Hot 97’s Peter Rosenberg had an interesting take on J. Cole’s apology. He said maybe someone of his stature would be able to model a new means of behavior. Maybe this has the potential to mark a new era in hip-hop—one where being at the top doesn’t make everyone automatic rivals or secret enemies. One that allows us to course-correct and disengage from unnecessary drama. One that allows us to grow up a bit. Regardless of how long it takes, we’ll have Cole to thank if it does. That’s what it means to build a legacy. That’s what it means to be great.