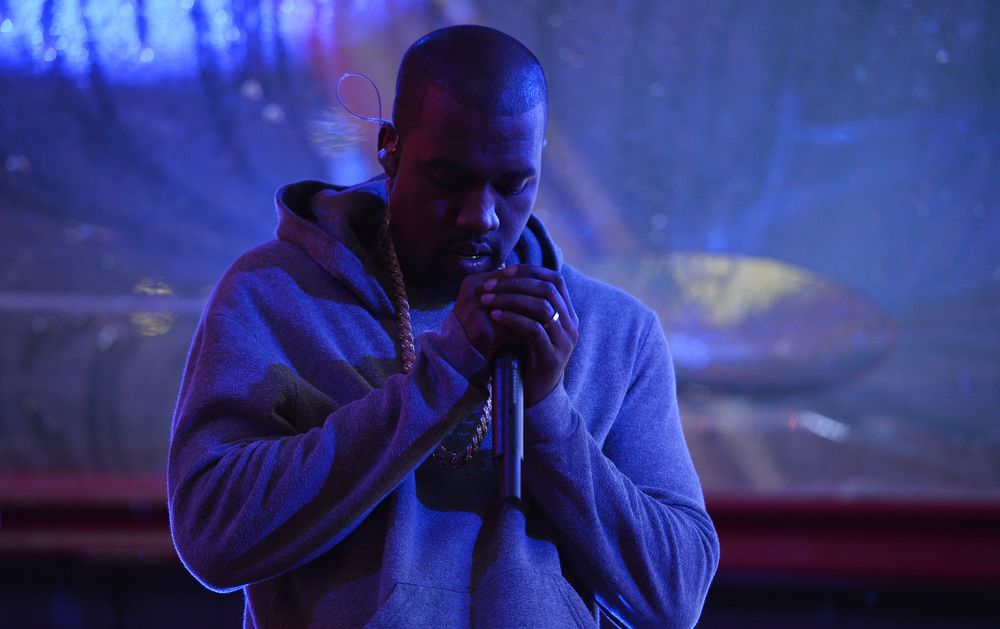

The beginning of Kanye West’s last great album sounds like a malfunction. Co-produced with Daft Punk, Ye’s “On Sight” is an acid bath of discordant synths, arrhythmic percussion, and scattered ideas—somewhere between industrial techno rap and a soundtrack for a fracturing psyche. Broadly speaking, it was the result of Yeezy’s latest artistic prerogative. After riding chipmunk soul, electropop, and themes of aspiration to Billboard Hot 100 dominance with the technique of a revolutionary but crowd-pleasing virtuoso, he’d set out to leave melody and top 40 radio behind. Ye was abandoning the pleasantries; he just wanted to be loud. Really loud.

“I know how to make perfect—but that’s not what I’m here to do,” West told BBC Radio 1’s Zane Lowe in 2013. “I’m here to crack the pavement and make new grounds… sonically and society, culturally.” Released 10 years ago, Yeezus stands as the start to the artist’s boldest and most shocking attempts to do so. It’s a mosaic of guttural shouts, glitchy production, machismo, political ruminations, and outright nihilism. At the time it was released, Kanye’s sixth solo studio album was nearly as polarizing as future Trump meetings, late-night Twitter screeds, and his ill-fated runs for president. More symbolically, Yeezus marked the end of the Old Kanye era.

For Yeezus, Kanye abandoned the elegance of conventional musical structures for blunt force, teaming up with Rick Rubin to simplify the sounds and strip the melodies. Whereas The College Dropout charmed listeners with underdog anthems, themes of self-improvement, and spirituality, Yeezus charged forward with fortified arrogance and sacrilege. The playful innuendo of “Slow Jamz” gave way to the NSFW nature of “I’m In It”. The acoustic guitar and self-consciousness of “All Falls Down” is traded for the raging tribal drums and frenzied shrieks of “Black Skinhead.” “Jesus Walks” became “I Am a God.” While Yeezus’ themes are scattered, they’re threaded by decisiveness and venom. Rather than reconciling conflicting feelings, Kanye isolates them, turning impulses and sensations into a battering ram.

One fellow Chicago artist who pulverized his way into the mainstream was Chief Keef, whose breakout single “I Don’t Like” was given a G.O.O.D. Music facelift the year before Yeezus’ crash landing. They teamed up properly on “Hold My Liquor,” on which Ye skitters over an ominous, ambient synth line. It’s a post-breakup song, but it careens into the type of acidity that’s a lot more diabolical than unresolved feelings: “One more hit and I can own ya/One more f**k and I can own ya.” Fused with Keef’s muted melody, it plays out like a demented sequel to “Say You Will,” the opening number on 808s & Heartbreak (which marked Kanye’s first major musical pivot). It’s a haze of corrosive masculinity rendered to compelling effect.

Indeed, Yeezus is as brilliant as it is forceful, but it scans as a dark, twisted premonition of the Kanye we know today, mapping out a journey that oscillates between expected and bewildering levels of self-parody. To quote one of Yeezy’s best loosies, the album is bittersweet, with each micro accomplishment serving as a reminder of the storm that was to come. We should be able to appreciate that “Blood on the Leaves” seamlessly blends an anthemic C-Murder sample with themes of dead romance and vocals from Billie Holiday’s poignant, anti-lynching anthem, “Strange Fruit.” But five years after that song’s release, Kanye insisted that slavery was a choice. “Hold My Liquor” should just be a toxicity anthem, but instead, when listened to present-day, it’s also a reminder of how Kanye humiliated his exes Amber Rose and Kim Kardashian in a very public fashion.

After calling out George Bush on live TV, Kanye wasn’t supposed to align himself with a White supremacist. “Black Skinhead” should be an ironic song title, not a new way to describe a rap legend.

Those songs deal with abstract feelings, but they conjure ugliness rooted in the real world, too. “New Slaves” verbalizes the roadblocks in Kanye’s quest for global dominance. On the track, he critiques racism in the fashion industry: “Doin' clothes, you woulda thought I had help/But they wasn't satisfied unless I picked the cotton myself.” Speaking on the matter during a fraught Sway’s Universe interview later that year, Kanye lamented a lack of support from the industry. When Sway Calloway suggested that ’Ye fund and launch a brand on his own, ’Ye scoffed before launching into an infamous tirade that became a meme that’s still quoted today. Their exchange is embedded with the underlying—if not outright stated—question: How can Kanye West get enough power to do any and everything he wants? Kanye didn’t believe Sway had the answers, and shortly thereafter, ’Ye began looking for them on his own.

By December 2013, Kanye left Nike for Adidas, relaunching a new version of his namesake sneaker that eventually became as popular as any footwear on the globe while making him richer than he’d ever been. Instead of circumventing his obstacles, he began commandeering them. On The College Dropout’s “Spaceship,” Kanye recalls stealing from the Gap as an employee. By 2020, he’d signed a deal with the same company, producing a line of apparel that was once valued at $970 million. After years of supporting Donald Trump’s polarizing presidential reign, Kanye eventually sought to follow in his footsteps. By then, his net worth was estimated at more than $1 billion. After reflecting on the cost of influence on songs like “Power,” ’Ye had essentially become the power he’d previously wanted to wield, with seemingly no checks in place.

This newfound wealth and influence didn’t necessarily propel Kanye’s art skyward, though. After previously executing album rollouts with meticulous precision in the first half of his career, Kanye’s subsequent releases became messy, often postponed (The Life of Pablo) or released in audibly unfinished forms (Donda). The projects are more vapid (Ye) and less poignant than their predecessors. And yet, people continued to listen.

Even after being a shill for GOP elite, reducing slavery to a lifestyle arrangement, and teaming up with the most crooked politician in recent American history, Kanye West’s monthly Spotify stream count sits at around 56 million—and that’s without Donda 2, the 2022 album he released exclusively via the audio device and streaming platform Stem Player, which he developed in partnership with UK tech company Kano Computing. Adidas attempted to end its partnership with Kanye due to his antisemitic remarks, but the brand was forced to deal with him again simply because it would lose too much money otherwise.

Like Kanye himself, Yeezus remains abrasive yet hard to turn away from. Ugly, but maybe essential. Ten years after its release, it feels like schematics of what was, what is, and what shouldn’t have been. Kanye can still be charming, but in the Yeezus era, his interviews grew more aggressive. His ideas were always extreme, but now they’ve become as hateful as they are inane, reflecting the scabrous tone of his 2013 opus. It’s easy to lose track of Kanye’s pre-Yeezus f**kery when basking in nostalgia, but the fact remains: After calling out George Bush on live TV, Kanye wasn’t supposed to align himself with a White supremacist. “Black Skinhead” should be an ironic song title, not a new way to describe a rap legend.

For those paying attention, it was clear Kanye recognized the career metamorphosis he was undergoing one decade ago, around the time of Yeezus’ release. He said as much in the aforementioned conversation with Zane Lowe. “People are going to look at this interview and say, ‘I don’t like Kanye. Look, he looks mad. I don’t like his teeth,’” Kanye prophesied. “They’re going to say, ‘Why doesn’t he just focus on music? I liked him as music.’ They’re going to say, ‘Hey, I want the old Kanye, blah, blah, blah.’ But one thing they will do, they will play this interview in five years. They will play this interview in 10 years and say, he called that. He called that. He called that. He said that was going to happen, that was going to change.”

It’s reductive to say Yeezus marked the birth of New Kanye, because, well, it seems like there’s a new one every few seasons. Since then, he’s formed gospel choirs, become a father of four, and launched his own school and sports agency. His multitudes continue to multiply as the years pass, leaving shutter shades and anthropomorphized bears in the rearview.

On “Last Call,” ’Ye recounted his career elevation with an endearing sincerity that made his wins feel like yours. In the wake of tone-deaf tirades and the increasing self-absorption of songs like “I Am a God,” his accomplishments feel like rules of a world that loves the powerful unconditionally. The underdog story ended a long time ago. Now, instead of being excited for the future, many of us are remembering what was. And instead of celebrating an anniversary, we’re mourning a death.