It took me a few watches to find the humor in Life.

The first time I saw it, I couldn’t laugh at all.

All I saw were two innocent Black men serving life in prison for a crime they didn’t commit. Two regular men who happened to be in the wrong place at the wrong time, punished not for murder, but for existing in a country that’s always needed Black labor but never wanted Black freedom.

It didn’t feel like a comedy; It felt like grief disguised as laughter. And maybe that’s the point.

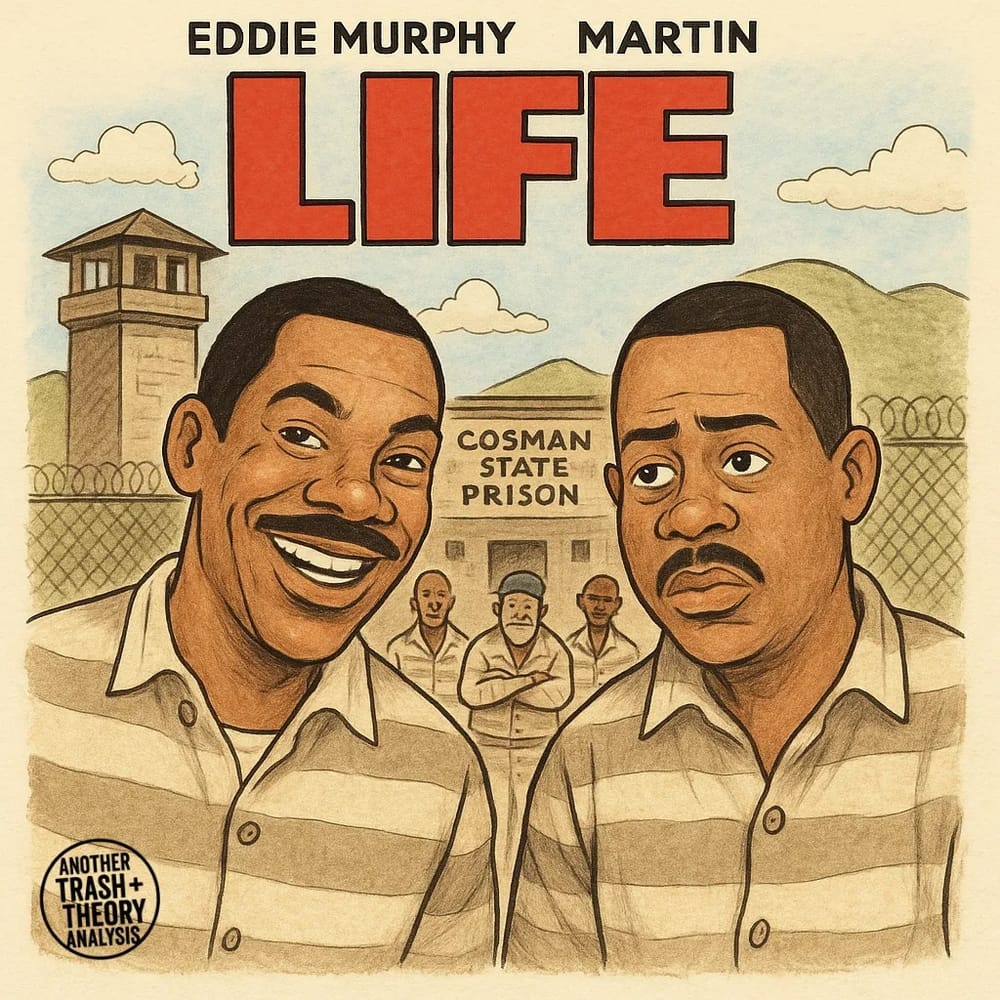

Life opens in 1932, when two strangers, Ray Gibson (Eddie Murphy) and Claude Banks (Martin Lawrence), were framed for killing a white man in Mississippi. One hustler and one banker, but both Black and innocent.

The setup is supposed to be funny: the odd-couple banter, the bad luck, the schemes gone wrong. But it’s also eerily familiar. The justice system doesn’t need proof when it has power. And once that gavel drops, their real sentence begins: decades of unpaid labor in a “correctional” facility that looks a lot like a plantation.

Because here’s the reality: wrongful convictions are way more than movie plots; they’re an American tradition.

Black Americans make up only about 13% of the U.S. population, but more than half of all exonerations since 1989. They are 7.5 times more likely to be wrongfully convicted of murder than white people, and nearly 60% of all people freed by The Innocence Project have been Black. In drug cases, about 69% of those later proven innocent were Black, even though usage rates are roughly the same across races.

So when I watch Life, I don’t see a “buddy comedy.” I see a historical record, and one that repeats itself generation after generation, with better lighting and worse excuses.

The brilliance of Life is that it hides tragedy inside humor, forcing the audience to do emotional math in real time. You laugh, then you realize why you’re laughing…and it hurts.

That’s the paradox of being Black in America: learning to laugh at what should break you. Ray and Claude’s quick wit and sarcasm aren’t just comic relief; they’re survival mechanisms. Every joke is an act of resistance; Every roast, a reclamation of dignity.

That’s how we’ve always survived, by making the unbearable a little more bearable.

We’ve learned to make lemonade of lemons and delicious pie from even the most bruised sweet potatoes.

Life isn’t just about incarceration, but theft of time. The prisoners lose everything: youth, love, ambition, identity. They grow old in a system that doesn’t even remember why it caged them.

By the time they escape, decades have passed, and they have spent their best years paying for a crime they didn’t commit. Their families are gone. Their names are forgotten. And let’s not even talk about the times they almost got out of their cells, including when the warden dies right after finally realizing they were innocent.

Even though we’re glad they finally escaped, the victory is hollow. Even their freedom, when it comes, feels too small; like getting a refund for a life you can’t re-spend.

That’s the most haunting part, while it seemed like Life in prison, the real punishment was invisibility. They were removed from society for their entire lives,

And things like this are still happening now…only with better marketing.

What starts as rivalry becomes a reluctant brotherhood. Ray and Claude bicker, insult, and clown each other, but beneath all the roasting is intimacy. It’s one of the rare times Black male tenderness is shown without sentimentality.

They built a family where the system tried to erase it. They laugh because if they stop, they’ll cry. They fight because that’s how they stay alive. By the end, their friendship feels more real than any romance Hollywood offered us that decade.

Even their eventual “freedom” comes through the performance of pretending to die. It’s poetic and cruel: the only way for two Black men to be free is to disappear.

That’s how America works: it never grants true liberation, just illusions of escape.

And still, they find joy, dream, and manage to steal little moments of laughter from a system that was built to consume them whole.

That’s the part I finally learned to appreciate: not just the jokes, but the strength it takes to make them despite their circumstances because Life isn’t funny.

It’s about the absurdity of surviving a country pushing you to die.

Every time I rewatch Life, I think about how much it mirrors our reality.

The cages look different now: sometimes digital, sometimes financial, and sometimes psychological. But the core story stays the same: someone profits while someone else does time.

And that’s why Life hits harder than most serious dramas. Because behind every punchline is a system, and behind every single laugh is a major loss.

This isn’t just about Ray and Claude, but all the Black men and the women waiting for them, still doing time in a world that calls injustice entertainment and treats it as spectacle instead of living, breathing trauma.

This post originally appeared on Substack and is edited and republished with author's permission.