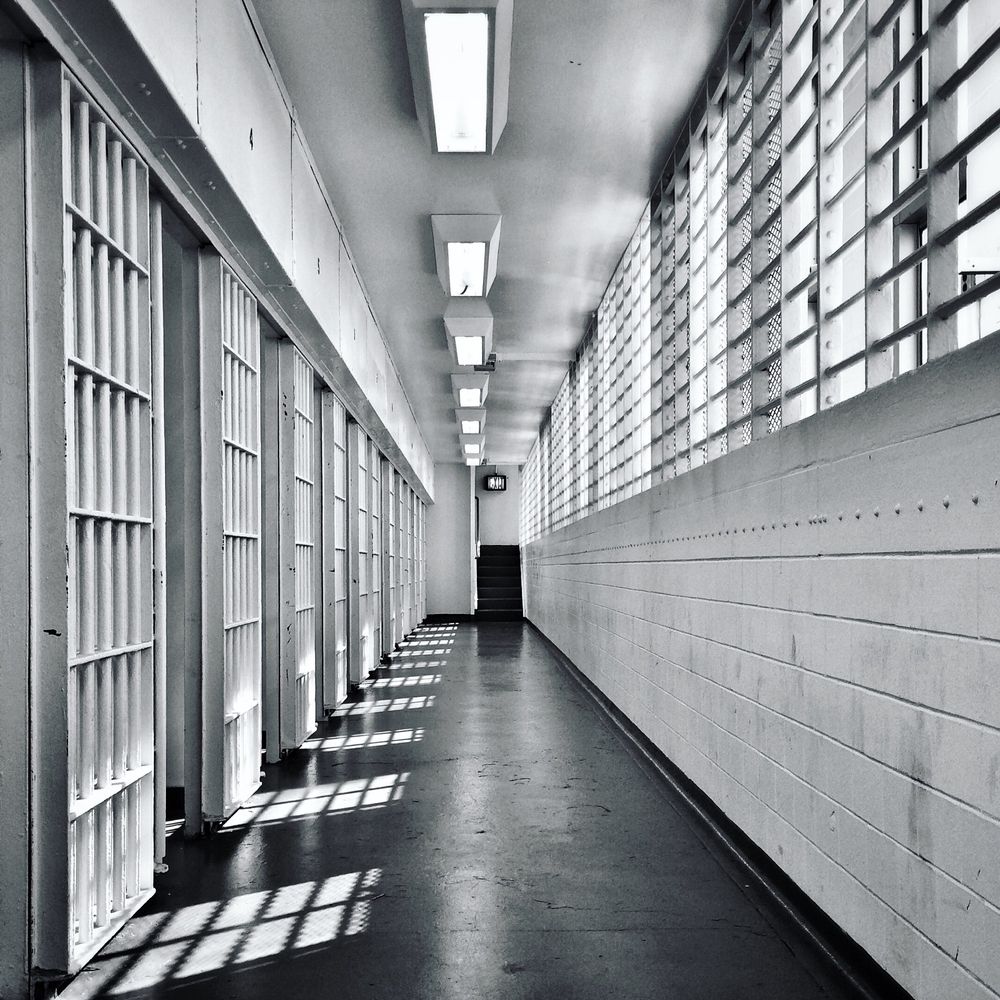

He’s not on the mic much these days. But that doesn’t mean Trevell Coleman — once known as G-Dep, the Bad Boy-signed MC whose song “Special Delivery” electrified 2001 and spawned a hell of a remix — doesn’t have something to say. Nine years into a 15-to-life murder sentence, Coleman shares the fear and concern that Covid-19 has introduced among inmates at New York’s Elmira Correctional Facility. From inside, Coleman reveals how he found out about the virus and what the reaction has been from the inside.

Since the beginning of the year, we’d all been in our day-to-day routine: watching television, going to work, recreation, and then evening programs. The days come in and go out, with little changing on the inside.

But then one day in March, there was a buzz in the facility. We could hear people whispering about some kind of virus circulating in the outside world. At first, there was an air of disregard and skepticism and even outright disbelief. A highly contagious virus spread by droplets in the air and deadlier than the flu? You need to be six feet apart or wear a mask? It’s hitting vulnerable populations in enclosed places like nursing homes — and prisons?

It sounded like a movie. But pretty soon, the dismissal and denial became paranoia and panic.

It was true, and places like nursing homes and prisons were expected to get hit hard.

Not only did we have to worry about our health here on the inside, but we had this stressor created for our people on the outside. Beyond what might happen to us, the whole world was in danger. As the convict population became more in tune with the news broadcasts and reactions from loved ones and family members via phone and email, it was apparent this was not a test.

Those of us who work inside of the prison had our already low wages lessened — or had our jobs cut completely, mostly because there was no way to socially distance. And inmates don’t receive stimulus package assistance when they lose their jobs.

We’d never seen anything like this in our lifetimes. Although there are plenty of people in prison who are up there in age, none of them have seen this.

The first impulse for most was to self-isolate from the general population. But that wore off; eventually, being careful switched to being brazen. Because we’re in a prison in a small town like Elmira, we were nonchalant at first. Less people meant less chance of exposure. Right?

We started to feel like we were in a protective bubble. The jails were always keeping us in — but now, they were also keeping the virus out.

Or so we thought.

By late March there was a slight difference in general population. There was the usual mundane gossip, but there was also this feeling of solidarity. A oneness. A common awareness of our shared vulnerability. We knew we were at the mercy of those in charge — even more so than usual.

And we had no information. We just sat together comparing notes from the outside world.

We can just drink germicide .

But then we’ll…die.

The sun kills it. So you only have to wear a mask at night.

That doesn’t make any sense!

The virus is fake anyway.

Anything is possible.

For a while, meals were still being served regularly, and only a few prisoners were practicing social distancing for their peace of mind.

Some people, like myself, were still in their labor detail. One day, a civilian burst into my work area, arms flailing.

“Stop,” he said. “Right now! There’s an emergency.” We were all shuttled to our cells. We all figured this was something routine, that we were being locked down for some punitive reason.

It turns out it wasn’t punitive — it was preventative. The president had declared the virus a global pandemic and the governor of New York was implementing a lockdown in the state of New York.

People probably think that since we’re in jail, we weren’t significantly affected economically by this pandemic. That’s not true. When our people and our support on the outside are hurting, we are too. We had loved ones and relatives affected by loss of work and health concerns. That hits us as well.

And those of us who work inside of the prison had our already low wages lessened — or had our jobs cut completely, mostly because there was no way to socially distance. And inmates don’t receive stimulus package assistance when they lose their jobs.

The effects of the coronavirus began to trickle down even more when commissary deliveries from our families became limited due to inventory and worker shortages.

There were other challenges. At first, we had to improvise our protective gear on our own. Many of us made makeshift masks with whatever we had. Some used winter gloves in place of plastic ones. Some decided to just self-isolate. We were eventually given real masks after a week in lockdown, and then proper protocols and social distancing began. We skipped a seat during meals in the mess hall and no one sat across from you at the table. The process took longer because fewer people were in there at a time, but it was effective. (And more sanitary than the old way anyway!)

Recreation changed as well. Instead of being in the yard with 150 people for two and a half hours, we’re now out there with 75 people for an hour.

And still, we had no idea if what we were doing was having an impact. Were we protected? Since there was no more visiting from outside, most of us watched the local news to see how the surrounding town of Elmira, New York, was faring with this pandemic. As long as their infection numbers stayed low (and they did), we knew there was less chance for anybody working at the jail coming in with it. That was — and is — our blessing.

Our visiting privileges have been reinstated, along with our recreation times. There is a certain feeling of normalcy. But until there’s a cure or a vaccine, we’ll still have to socially distance and be cautious.

People often think that prisoners don’t deserve rights, that whatever happens to us on the inside is our fault. But the people in here are humans. Whether they come here every day to work or are incarcerated, people are just trying to live.

I’m here, on the inside. I’m doing my very best to make it through. Prayers go out to everyone affected in any way — no matter your circumstances.

This virus knows no bounds. And God is with us all.