Lamar Johnson was driving to pick up his grandmother from dialysis in May of 2015 when a Baker, Louisiana, police officer pulled him over because his car windows were tinted. Four days later, a guard found the 27-year-old hanging in his cell at the East Baton Rouge Parish Prison.

Years before Covid-19 ravaged correctional facilities across the United States, the East Baton Rouge Parish Prison (EBRPP) experienced its own prolonged wave of death. From 2009 to 2019, 45 prisoners died in the jail’s custody, which is nearly double the national average. Most of the deceased had been arrested for nonviolent crimes and had not had their day in court.

EBRPP is a dilapidated, overcrowded facility that was built in 1965. Detainees there have spoken of bedbugs, spider bites, and rats in the stew. Residents of the parish rejected a tax to build a new jail, and Louisiana Gov. Bobby Jindal rejected Medicaid expansion, which shuttered the public hospital and privatized health care at the jail. Throw in an underfunded public defender’s office that often has to wait years for cases to go to trial, a Baton Rouge Metro Council that won’t allot the recommended funding in the city’s budget for humane treatment, and policies that do not protect the lives of incarcerated people. Taken together, these realities provide a clear picture of the criminalization of poverty in America, which can be a death sentence that disproportionately affects Black and Brown people.

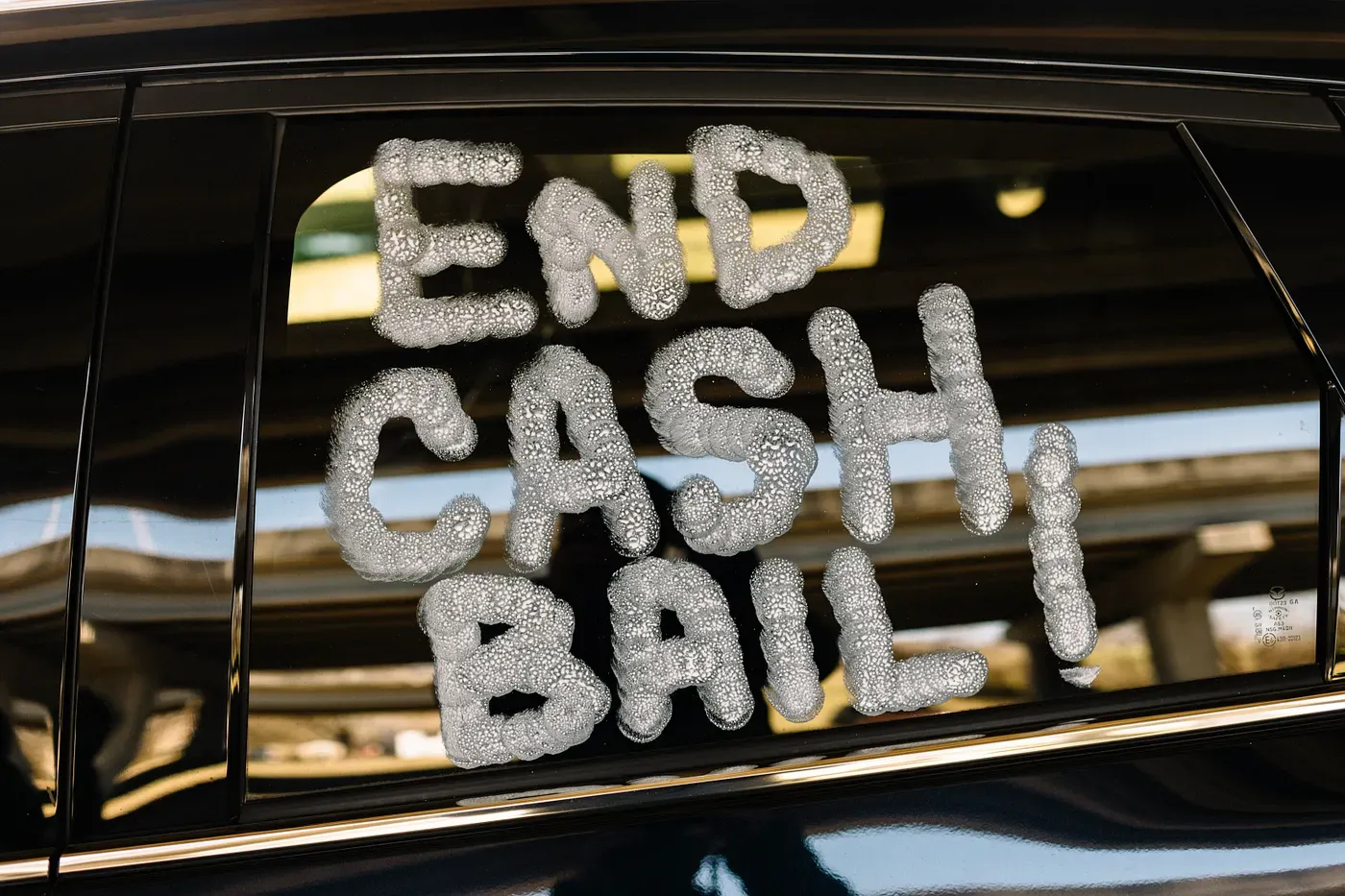

Jails primarily hold pretrial detainees who cannot afford cash bail, whereas prisons hold convicted people serving out their sentences. In other words, jails are intended to hold while prisons are intended to punish (and, theoretically, to rehabilitate). EBRPP is a misnomer as it is actually a jail. Casey Rayborn Hicks, public information officer for the East Baton Rouge Sheriff’s Office, says 90% of the people held there are pretrial. In the United States, defendants are presumed innocent until proven guilty, so each of the people who died at the EBRPP before having a trial died legally innocent.

Located across the street from the Baton Rouge Metropolitan Airport, the EBRPP is staffed and run by the sheriff’s office. It employs more than 350 deputies and houses both men and women, though the vast majority are male. In 2019, the jail typically held 2,000 people despite its 1,550 capacity. The sheriff, Syd Gautreaux, is an elected official who has held his position for 14 years. A few months after he started, he hired warden Dennis Grimes, who still runs the jail.

“It is a well-known fact that our facility is aged,” says Baton Rouge’s Mayor-President Sharon Weston Broome. “Parts of the facility are no longer in use based on design issues that make the addition of modern security standards for staffing unobtainable.” While the sheriff runs the facility, the responsibility for providing and maintaining it rests with the city-parish, which consists of the mayor’s office and the metro council. “Funding for such comes from our limited general fund,” says Broome. The city-parish is also responsible for funding health care for those held at the prison.

Prison reform advocates say the conditions at EBRPP are deplorable, and the treatment of those booked there has gone largely unnoticed by the greater Baton Rouge community. Many residents are unaware of the disproportionate number of deaths. “If it doesn’t affect you, then you don’t seek out that type of information,” says Linda Franks, Lamar Johnson’s mother.

Franks says there’s a shame factor that contributes to an unwillingness for families to come forward about experiences with the EBRPP. “We want not to be perceived as being those people,” she says, adding, “So sometimes when our children make mistakes or get into trouble, we’re less likely to share that information or to reach out in certain areas to get help.”

Another concern if someone has a loved one currently at the prison is a fear of retribution. “That’s a real threat,” Franks says.

In 2017, a year after Alton Sterling was murdered by a Baton Rouge police officer and the city erupted into weeks of protests, conditions at EBRPP came to light through a report called “Punished Protesters: Conditions in the East Baton Rouge Parish Prison,” published by the Promise of Justice Initiative, a New Orleans-based advocacy group. The report, co-authored by PJI staff attorney Erica Navalance and New Orleans’ Loyola School of Law professor Andrea Armstrong, chronicled the experiences of several of the approximately 180 protesters who, before being bailed out, spent time at the jail for infractions like obstructing roadways.

According to the report, the protesters experienced excessive force, intimidation, deliberate humiliation and racism, denial of medical care, unsanitary conditions, and inhumane treatment that included lack of access to food and water and the denial of their right to use a telephone. One woman said she was put in an overcrowded cell where her glasses were taken from her and she could not see. The report detailed how a 17-year-old was deliberately housed separately from her mother but with other adults and was strip-searched in a group of six women. At least two women were strip-searched twice during their detentions that lasted only one day, although between the searches, they’d had no contact with the outside world. A woman of color was told to permanently surrender her bra with metal underwire while several White women wearing the same type of bra were allowed to keep them on.

“One of the things that many of those protesters promised other people who were inside [the jail] with them is that now that they knew [about the conditions], they would continue to talk about it on the outside,” says Armstrong.

According to a 2017 article in The Advocate, Baton Rouge’s local newspaper, Warden Grimes defended his guards’ actions as “appropriate, professional, and well within constitutional standards,” adding that they “at all times acted appropriately.” He also denied the veracity of protesters’ claims.

“I just trusted that he was going to be safe because he was there with our honorable law enforcement, you know what I mean? I had no idea of how people were being treated [at EBRPP] until after he died.”

During the writing of this first report, Armstrong and Navalance made a commitment to complete a more extended piece, “looking solely at conditions, not through the eyes of the protesters, but through the people who had died in that jail because of the conditions,” Armstrong says. That report, “Dying in the East Baton Rouge Parish Prison,” was published in 2018 and details the experiences of the 25 men who died at EBRPP from 2012 to 2016.

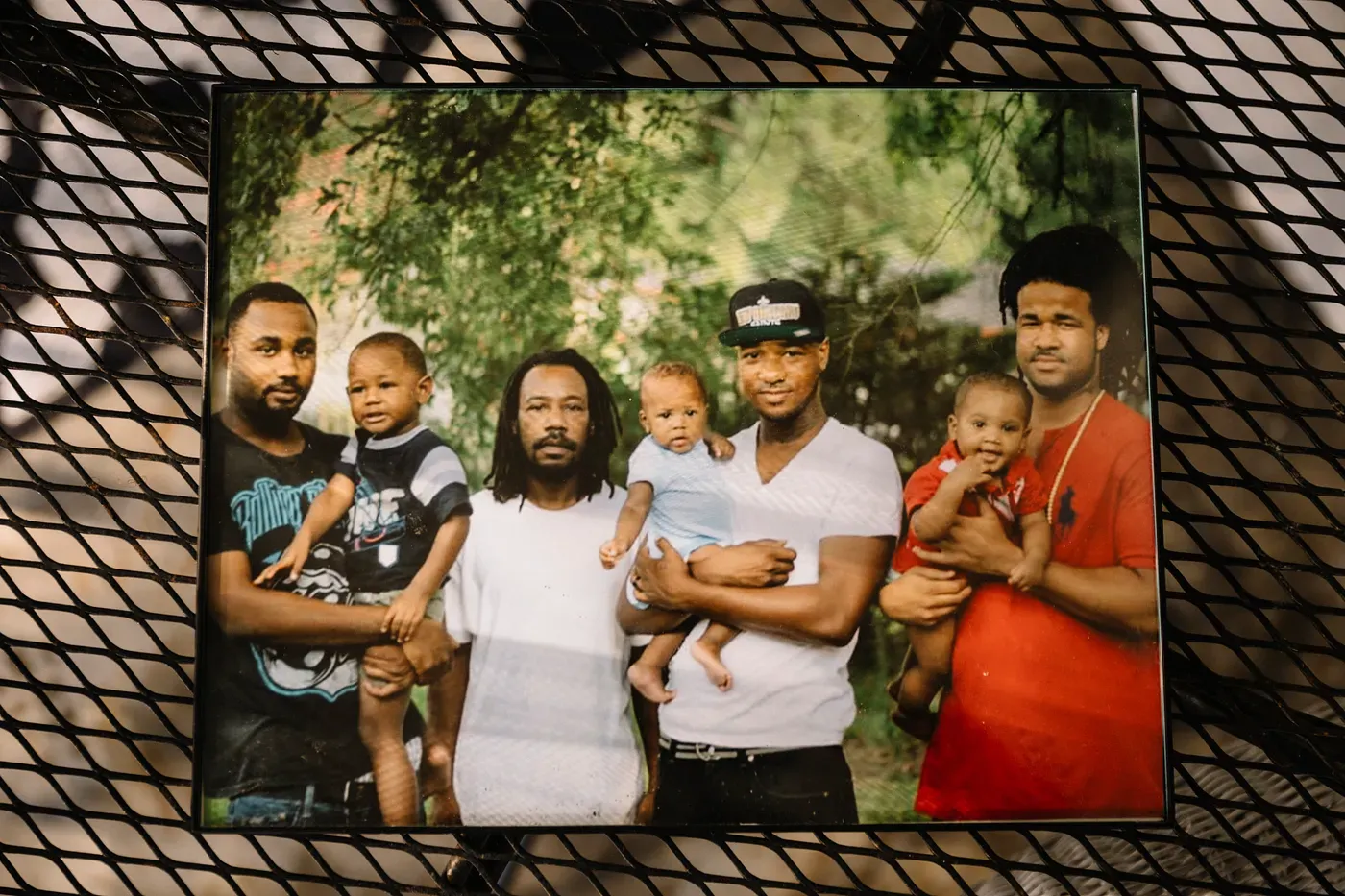

One of them was Lamar Johnson. Johnson grew up in Baton Rouge and had a two-year-old daughter. He attended art school in Atlanta and worked as a videographer. His mother remembered him as a person who always took people under his wing and who, when he was a child, went to a bullied, overweight classmate’s house every day to help him get fit. Johnson was an organ donor, and his autopsy report shows that after his death, his heart, spleen, liver, gallbladder, pancreas, both kidneys, and adrenal glands were given to those in need per his wishes.

Johnson knew when he was pulled over in 2015 that an unpaid traffic ticket for driving without his license on him was going to come up. He had been avoiding dealing with it and told the officer it was hanging over his head. At that point, he chose to just do the time and get it over with since he didn’t have the money to pay the ticket. What also came up was a record of a bad check he had written for around $300 five years prior in nearby Jefferson Parish. Franks says her son had never been arrested for this offense, nor even contacted, despite the fact that his name and phone number were on the check. But it was in the computer system, although she believes it should have been expunged due to the time that had passed.

According to the national nonprofit the Bail Project, nearly half a million people in America await trial from inside a jail cell each year while the accused who can afford to pay cash bail remain free. Recent research suggests that White defendants are half as likely to be detained pretrial than young Black men. Additionally, bail for Black and Brown defendants is generally set twice as high as their White counterparts. According to an ACLU report published in March 2020, Louisiana has long been considered the incarceration capital of the world. Pretrial incarceration costs Louisianans almost $290 million per year, the median bail for someone held pretrial in the state is $24,000, and the average length of stay pretrial with no conviction is five-and-a-half months. Prison reform advocates in Baton Rouge say detainees have been held at the EBRPP for as long as 11 years without a trial.

Sitting in the back of the squad car on that warm spring morning in 2015, Johnson was concerned about his grandmother, waiting to be picked up from dialysis. He asked the arresting officer if he could call his mother to let her know what was happening and that his grandmother would need a ride home. The officer agreed. “He said to me on the phone Lamar was very cooperative, that he was a standup guy. This didn’t seem to be anything serious, not to worry about it,” said Franks.

According to a 2016 story in The Advocate, police car video footage shows Johnson telling the arresting officer that he saw his arrest as “an opportunity to finally deal with the counts.” The arresting officer responded, “I admire that. Everything happens for a reason, and I believe in my heart you’re trying to do right because you’ve been honest with me since you stepped out of the car, and I respect that.”

The officer decided not to put Johnson through the expense of impounding his car and told Franks that Johnson’s girlfriend could pick up the keys from the Baker police department. She appreciated all of these gestures. And yet at the same time, she was terrified. “I’ve always been terrified. I mean, I’m not going to lie to you,” she says. “Raising three Black men in this society every day of my life, my biggest fear is that they will be accused of something that they did not do, that they will be brutalized or misunderstood and mishandled.”

After spending a couple of days at the EBRPP, Johnson was to be transferred to the Jefferson Parish prison. He called his mother from jail the next day. He and his brothers always checked in with her. If they broke curfew when they were teenagers, she told them that the minute they didn’t come home, in her mind they were either dead in a ditch or somebody hurt them. Even as an adult, Johnson would call his mom to check in. “That was his thing,” she says. “He called from the jail to let me know that he was okay and everything was going to be all right, that he could handle whatever was coming up and for me not to worry.”

Franks tried to take his advice. “I just trusted that he was going to be safe because he was there with our honorable law enforcement, you know what I mean?” she says. “I had no idea of how people were being treated [at EBRPP] until after he died.”

In jails across America, even one death per year is unusual, according to Armstrong, the Loyola law professor. “About 20% have one death within a given year,” she says. “And the percentage for having more than one death in a year is even smaller.” When asked about the death rate for detainees at EBRPP, public information officer Hicks cited the numbers for 2020 in an email. “There were three inmate deaths,” she wrote. “The facility is well below the national average for such pre-trial facilities.”

According to the Pew Charitable Trusts, Louisiana’s prison population peaked in 2012 at roughly 40,000, five times what it was in the 1970s. That same year was the deadliest of the past decade for detainees at EBRPP, with the deaths of eight incarcerated people. Among the dead was 40-year-old Daniel Melton. While he awaited trial and was unable to post bail, his repeated pleas for medication over a 24-hour period went unheeded before he succumbed from a peptic ulcer. Melton had mental health issues and had been put on lockdown in a one-man cell. He had complained multiple times to staff that his stomach felt like it was “going to explode.” In a wrongful death suit, his family was paid $25,000 by the City of Baton Rouge.

The following year, Louisiana Gov. Bobby Jindal declined Medicaid expansion for the state. This decision meant the shuttering of many state health care agencies, including the public Earl K. Long Hospital in Baton Rouge, which provided health care to those held at the EBRPP. It also shifted the health care costs for detainees at EBRPP from the state to the city as long as they were treated at the prison for nonemergency care.

Shackled to a chair, he screamed incessantly and was shot with a stun gun. … He remained in that chair for more than 170 hours with few opportunities to use the bathroom. The lacerations from his restraints became infected from exposure to his urine and feces.

Prison medical services took over medical care for detainees on-site at EBRPP in 2013. That year, three detainees died. One was David O’Quin, 24, who had been diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia as a student at the University of Texas, where he was studying studio art. O’Quin was in Baton Rouge when he stopped taking his medication and was suffering from serious psychosis at the time of his arrest. Shackled to a chair, he screamed incessantly and was shot with a stun gun. During the 13 days he was at EBRPP, he remained in that chair for more than 170 hours with few opportunities to use the bathroom. The lacerations on O’Quin’s ankles from his restraints became infected from exposure to his urine and feces. He died from blood clots that traveled to his lungs as the result of his confinement. In a wrongful death suit, his family was paid $50,000 by the City of Baton Rouge.

Neglect and abuse of detainees come at a significant financial cost. “EBRPP pays an exorbitant amount of money in insurance premiums every year and was paying close to a million dollars at the time of the reporting,” says Shanita Farris, co-author of PJI’s “Dying in the East Baton Rouge Parish Prison” report. “This facility was understaffed, and all staff were not properly trained or equipped to respond to medical needs and emergencies. Resources are better spent on ensuring safe and humane conditions.”

The sheriff’s office declined to comment on questions about whether corrections officers have specific training in handling people in psychiatric crises or who may exhibit violent behavior due to illicit drug use or withdrawal.

Lamar Johnson entered EBRPP in a healthy state of mind and fully cooperating with the booking officer. Within 48 hours, Johnson went from being relaxed and cooperative to paranoid, delusional, and suicidal. Though Hicks of the sheriff’s office says, “There is no evidence that Johnson indicated or communicated any suicidal thoughts or actions to any EBRPP deputy or official prior to him taking his own life.”

In an investigation conducted by the Claiborne Law Firm for lawsuits filed on behalf of Johnson’s young daughter, expert witness Dr. Homer D. Venters reviewed documents produced by Health Management Associates, a Chicago-based consulting firm hired by the city to review services at the jail in 2016. Health Management Associates recommended the budget be doubled for adequate health care.

Venters also reviewed depositions from Health Management Associates and EBRPP staff. His preliminary statement notes that significant barriers to accessing health care at EBRPP led to the ignoring of Johnson’s “loud, obvious, and repeated suicidal statements the night before his hanging.”

“He was on life support, intubated, and chained to a bed with a deputy sitting beside him. For a traffic violation and a minor check-cashing incident that wasn’t supposed to even be on the books.”

An internist, epidemiologist, and former deputy medical director at the Correctional Health Services of New York City, Venters is currently the assistant commissioner of the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. His report continued, “Systematic failures and gross deficiencies in the health care system for detainees at EBRPP directly contributed to the death of Mr. Johnson.” He had never received a health intake screening. The only documentation that he was seen by health care staff in any clinical capacity occurred after he was found hanging by the neck from a towel tied to the bars of his cell. Venters also cites systemic failings in leadership, training, and supervision that led to grossly incompetent and inadequate emergency medical care by the jail health staff who responded to Johnson’s hanging.

Depositions also included accounts from other prisoners. One testified that he heard security staff using excessive force on Johnson. Another testified that the night before he was found hanging, Johnson had been talking loudly to himself about not wanting to live. The East Baton Rouge parish coroner’s report found high levels of a metabolized version of THC, found in traditional cannabis, in Johnson’s blood following his toxicology report, indicating he may have had access to illicit substances while at the prison. The federal lawsuit filed on behalf of his daughter indicated his behavior may have been indicative of psychosis brought on by the ingestion of synthetic marijuana. Johnson was not tested for this substance at the time of his autopsy as this is not typically done unless there’s concern about prior use because the test can be expensive.

There have been several overdose deaths at EBRPP. The sheriff’s office declined to answer questions about how illicit substances might be getting into the jail or about screening procedures for those coming and going from it, including visitors and staff.

According to David Utter, the attorney representing Johnson’s daughter following his death, a lawsuit on behalf of his daughter against the city was settled for $135,000. A lawsuit against the sheriff was also settled out of court for an amount that is confidential.

Johnson’s story does not end with his hanging. He was taken to Our Lady of the Lake Hospital and put on life support. He died 10 days later, after being declared brain dead and having his organs harvested. According to Franks, her son was on life support for three days before she and her husband learned he was found hanging in his cell, and it was only because she had called the prison and was told her son was sick and had been taken to the hospital.

When she and her husband showed up at the neurointensive care unit unannounced, they were told they had to have the warden’s permission to enter Johnson’s room. When she called the warden, she was informed she would have to drive across town to the prison with documents proving she was Lamar’s mother before she could go in. Even after doing so, only Franks was let in. The warden would not allow Johnson’s father or brothers to see him. Johnson says the warden kept saying, “‘I’ve got to protect my prisoners.’ And I’m like, ‘This is not your prisoner; this is my child.’ And he was just there for a traffic ticket. So I don’t know what you’re trying to say. Protect? Protect him from what?”

Franks went in to see her son by herself. “He was on life support, intubated, and chained to a bed with a deputy sitting beside him,” she says. “For a traffic violation and a minor check-cashing incident that wasn’t supposed to even be on the books because of the antiquated computer system.”

The sheriff’s office did not respond to a request for the warden’s version of these events.

Franks recalls the warden later telling her husband, “It is what it is.”

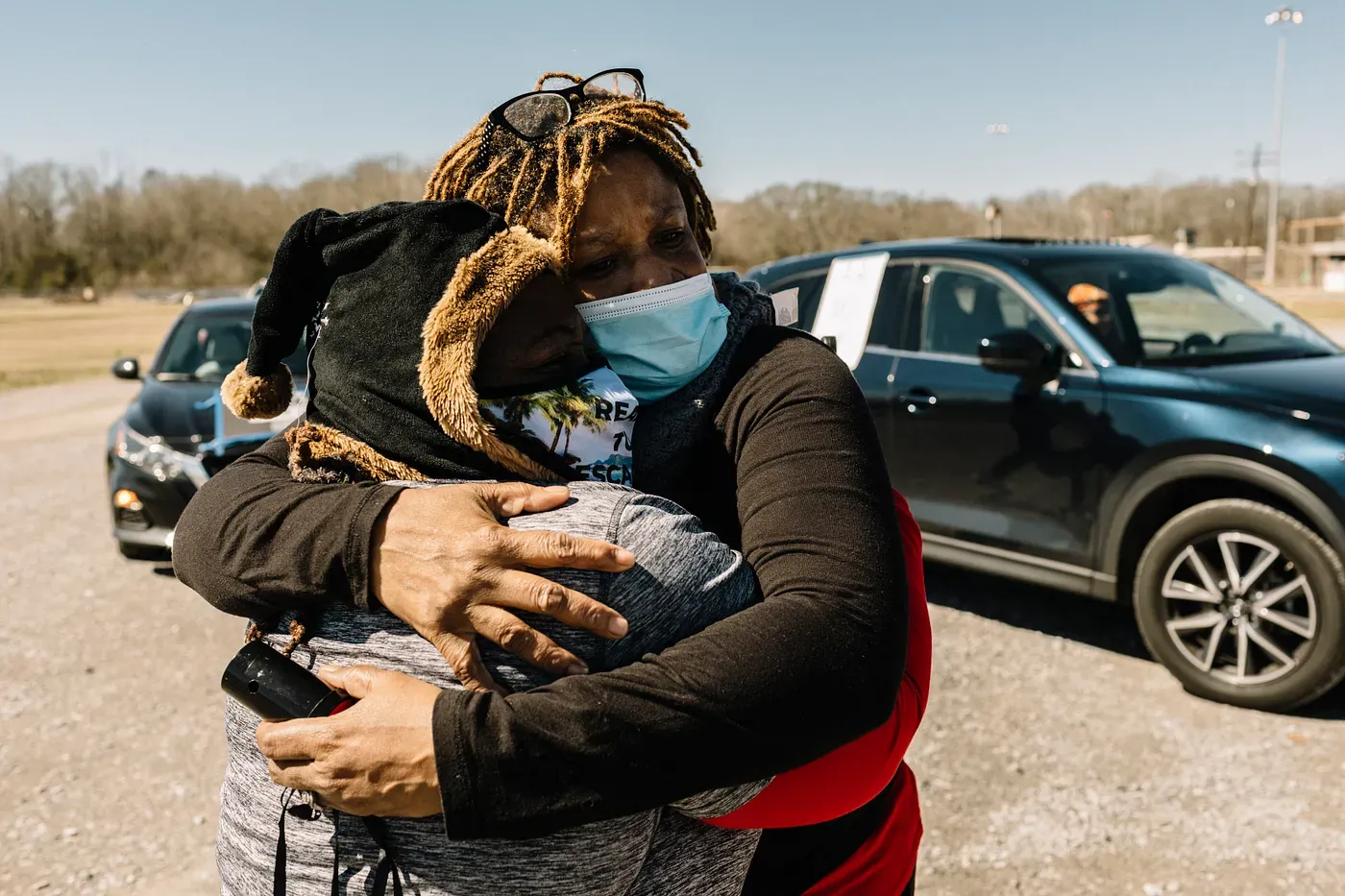

In January 2018, Franks became one of the founding members of the East Baton Rouge Parish Prison Reform Coalition, a community advocacy group formed at a local library “to bring reform and an end to the inhumane and at times deadly conditions at the EBRP Prison.”

Franks is currently the board chair. The group is composed of concerned citizens: mothers, fathers, artists, activists, and law school students. Like the Franks, several in its core leadership have lost a loved one at EBRPP. Rev. Alexis Anderson, an outreach minister ordained in the African Methodist Episcopal Church and a member of the coalition’s steering committee, attributes its formation to everything that went wrong surrounding the death of Lamar Johnson.

“There was nothing about that situation that should have ended up in death,” Anderson says, later adding that Lamar was one of her favorite people in the world. She described the formation of the prison reform coalition as “a gathering of people trying to figure out what happened but also how to make sure it never happened again.”

There had been hope among some metro council members in 2017 that privatizing health care at the prison would have brought improvements. But rather than taking the recommendations made by Health Management Associates and doubling the prison’s health care budget to $10 million, the metro council decided to privatize and went with Atlanta-based CorrectHealth, which would cost the city just a small amount more than what they were already paying.

“Prior to my term in office, our metro council voted to outsource our medical services based on ongoing service issues at the facility,” says Broome. “The rush to make this shift happened when the medical director resigned. … The contract for services was done through a professional services contract, not a [request for proposal].”

On average, privatized health care in jails incurs higher death rates than those that government agencies manage, according to a Reuters data analysis. According to reporting in The Advocate, around the same time Baton Rouge officials were discussing a contract with CorrectHealth, “the company was facing criticism in Savannah after officials there hired an independent monitor to assess medical services in their jail following a string of deaths.” CorrectHealth also had the disturbing distinction of having a physician CEO willing to perform prison executions, a practice frowned upon for violating ethical standards for doctors.

Under the watch of CorrectHealth, more than 20 additional detainees died at EBRPP, including Shaheed Claiborne, 41, who hanged himself in late January of 2020 with his cloth jumpsuit. He came to EBRPP during a mental health crisis and died after having been taken off suicide watch by a CorrectHealth employee. Claiborne was an award-winning food truck chef who appeared on local television shows and was the son of the late Rev. Betty Claiborne, a Baton Rouge civil rights activist who in the 1960s attempted to get into a “Whites only” city-run swimming pool along with her sisters before being stopped by the police and arrested.

According to Broome, the existing contract with CorrectHealth provides eight hours per week of a psychiatrist’s services, 24 hours per week of a nurse practitioner for mental health, and 40 hours per week of the services from a licensed social worker assigned for mental health. A local social services agency provides additional general counseling services, including substance abuse counseling two to three times per week. None of those hours helped save Claiborne, however, whose family filed a federal lawsuit on behalf of his children stating CorrectHealth employees did not pick up on numerous red flags that he was suicidal. These included approximately 10 hours of him stating repeatedly that he was going to kill himself, speaking in an unknown jargon, singing spirituals, and talking about his mother, who had died days before he was arrested.

A couple of months after Claiborne’s death, Covid-19 arrived in the U.S., throwing decision-makers into a tailspin over how to house people without turning their facilities into super spreader locations. As the first cases broke out at EBRPP, detainees who tested positive for the virus and didn’t require hospitalization were sent to the Louisiana State Penitentiary at Angola to quarantine in a section of the prison that had been closed for safety concerns. Angola’s population includes prisoners serving life sentences, many of whom are elderly. In late March, a prisoners’ rights group petitioned a federal judge to prohibit transferring Covid-19 infected detainees to Angola, arguing this would “expose the most vulnerable people in the DOC system to an unconscionably high risk of death or serious harm.”

Covid-19 positive detainees were later housed in three wings of the EBRPP prison that had been closed years earlier, also for safety concerns. By late May, 70 people tested positive at EBRPP, and civil rights organizations, including the Fair Fight Initiative, filed a class-action lawsuit alleging the jail was so overcrowded that people detained there could not properly socially distance and that the previously closed wings being used for quarantine space were “ridden with mold, filthy, and vermin-infested.”

The lawsuit was dismissed in 2020, but a motion was filed in March of this year urging a federal judge to reinstate it on the grounds that the court disregarded facts detailing profound medical neglect inside the prison. According to Fair Fight Initiative executive director David Utter, a consistent theme the organization is hearing from people currently in the jail is that officials there move people in and out of the so-called quarantined areas every day, directly violating the Center for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines that they claim to follow. A statement on the Fair Fight Initiative’s website adds that prisoners with Covid-19 symptoms have been confined in these cells nearly 24 hours a day, did not receive regular medical assessments, and, when asking for extra time out of this solitary confinement to shower or make phone calls, were beaten, maced, and threatened by guards.

A silver lining during the pandemic was that Baton Rouge law enforcement agencies made fewer arrests for nonviolent crimes while judges, prosecutors, and public defenders worked together to release some pretrial detainees who could not afford bond. According to the mayor, the facility’s population has been reduced to 950 people, more than half what it has been in recent years. There has been a 0% Covid-19 transmission rate within the inmate population at EBRPP since May 2020. “Most importantly, we have had zero deaths due to Covid-19 to date,” Broome says.

Other positive changes have come to the prison in the past year as well. In February, the Bridge Center for Hope, a 32-bed short-term stabilization facility for those experiencing mental health and addiction crises, opened. It is expected to serve as many as 5,000 people per year. “In its first days of operation, 38% of those being served were brought there by law enforcement, thus avoiding a possible prison stay,” says Broome.

The mayor’s office formed a Criminal Justice Coordinating Council funded by a MacArthur Foundation Grant and general fund dollars to further reduce the prison population. The public defender’s office has been working through a grant to assist people in bonding at the time of arrest to reduce long stays at EBRPP. “We are moving in the right direction through these efforts,” Broome says.

The mayor has also put out a request for proposal last month that may replace CorrectHealth.

Sheriff Syd Gautreaux and Johnson’s mother, Linda Franks, have something in common. Both would both like to see the EBRPP torn down and replaced with a modern facility. But Franks would also like to see voters elect a new sheriff, one who would clean house and replace the warden and any staff who were complicit or who looked the other way from the inhumane treatment of those held there.

Warden Grimes, Franks says, comes from a background in corrections, and in her view, he has run the jail like a prison with an “us against them” culture that views detainees as deserving whatever they get simply because they have been arrested.

“It just goes in the face of everything that this country is supposed to be about,” Franks says. “We understand the 13th Amendment, and once you’ve been convicted, of course, you lose certain rights. But before you get your due process, you’re still a full-fledged citizen of the United States, afforded all of the rights that come along with that. And that’s not being done. Especially in the South, that’s not being done.”