I don’t remember the first rapper I ever interviewed — a 20-plus-year career in journalism will do that — but I definitely remember the first rapper I thanked: Common, aka Lon-chikka-Lonnie Lynn. This was back in the Like Water For Chocolate era; as we sat there in a New York hotel room talking about everything and nothing at the same time, I realized that this dude had already made three albums that had hit me at different points in my young life. The hyperactive yawping on his debut, Can I Borrow a Dollar?, slid perfectly into my adolescent, Das EFX-loving ears. A couple of years later, Resurrection matched up with me being out of my folks’ house and learning how to think for myself. And with its first Soulquarian stirrings, One Day It’ll All Make Sense found me fresh out of college, navigating grown-man B.I. and wondering what my next step would be. It wasn’t that he was in my top five, or that I awaited each new album; it was that his music somehow acted as a soundtrack, in ways I hadn’t necessarily even realized.

So sitting there with him in 2000, as our conversation wound down, all that gratitude came rushing out. The appreciation of hearing someone growing up on a mic, in a way that felt like it paralleled my own experience. That was the sentiment, at least; somewhere there’s a microcassette in a shoebox with the actual words etched on its magnetic tape, but the only thing worse than listening back to an interview is doing it twice, so paraphrase is all we’ve got. Common’s response needs no paraphrase, though, being exactly what you’d expect from Common: “What’s your sign, dog? Pisces? I knew it!”

That coda (mine, not Common’s) became a post-interview ritual of sorts over the years for certain artists, a way to wrap things up with a note of thanks — not for the interviews, but for music that reflected where life had taken them. Invariably, those artists were what you might call “of a certain age”: Guru, Ice Cube, Black Thought. These little moments weren’t fan appreciation as much as they were flowers, an acknowledgment that the trajectory they enjoyed isn’t a given. For an artist to grow might seem like a natural instinct, but the economics of popular culture make it all too easy to resist.

Related: Who’s Having the Best Rap Career After 40?

The arc of hip-hop is long, and it bends toward youth. Always has, ever since an 18-year-old Kool Herc hosted his first party in the South Bronx. Thirtysomethings don’t usher in cultural revolutions. And even as the music transitioned from underground upstart to default aesthetic, the kids found ways to stay in charge. The blog era used MP3s and mixtapes to tear down the supremacy of gatekeeping record labels. Social media and SoundCloud became frighteningly efficient paths to stardom, empowering emerging artists to cultivate diehard fan bases before they’d finished a demo or played a single live show. YouTube turned YoungBoy Never Broke Again and Rod Wave into massive stars who even more massive chunks of the population had never even heard of, let alone heard.

Life happens, and its events and transitions can’t help but rewire the creative brain. Marriage. Parenthood. Loss. Vulnerability. Awareness of your place in the world. Inevitably, those things creep into your music, whether through subtext or sentiment.

Despite what screwfaced dudes in oversized jeans will tell you, this is all exactly how it should be. Hip-hop lives it because it changes. But change doesn’t have to be restricted to personnel turnover, an endless stream of rookies of the year and careers that burn bright and short. When youth is who you cater to, youth is where you get stuck. That’s why people grow out of Drake; for all his stratospheric success, the only thing dude has expanded in the past few years is his Duolingo library.

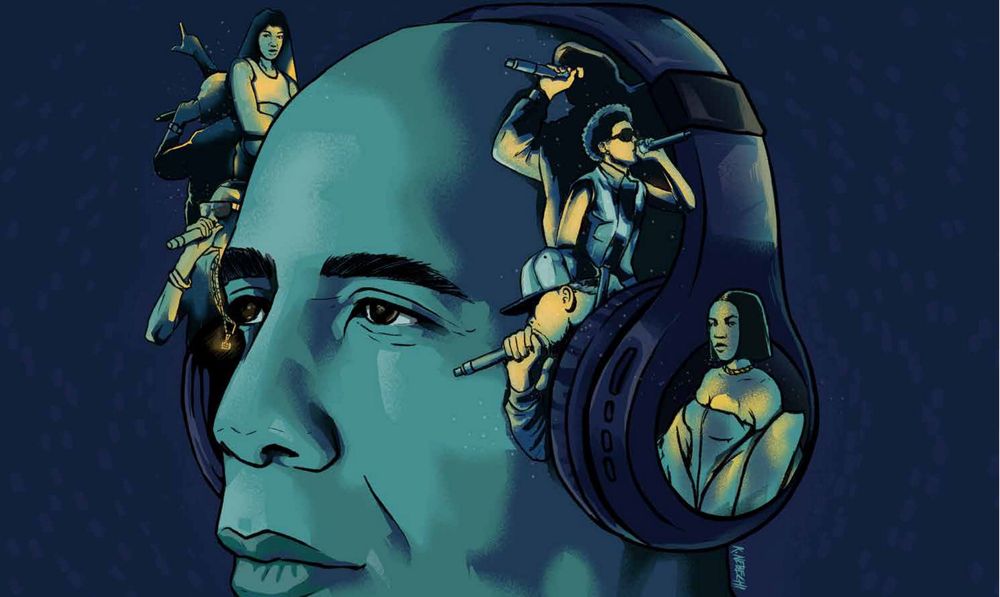

Meanwhile, a nation of 40-year-olds that grew up with hip-hop is still listening to hip-hop, and not in that stuck-in-amber way that you see with Beatles obsessives or ’80s fans. They don’t want to listen only to the music of their younger years — they want new shit that blows their ears and their minds. But they also want shit that hits them where they live. Relatability. Life experience. And increasingly, artists are carving out space in an industry not built for them to make music that does just that.

Jay-Z was months away from 40 when he dropped The Blueprint 3. The late Sean Price was 40 when he dropped Mic Tyson. Pusha T was 41 when he dropped Daytona. Killer Mike and El-P were 41 when they dropped Run the Jewels 3. These aren’t merely good albums; these are joints you still play today. And with the exception of King Push, all went on to release other albums — all of which proved that fortysomething rap isn’t a matter of fluke, but fluency.

In 2007, a botched Lupe Fiasco performance kicked off a heated debate about A Tribe Called Quest’s relevance in today’s hip-hop; nine years later, their swan song We Got It from Here… Thank You 4 Your Service turned out to be one of the best albums of the year. Last year, Little Brother pulled a similar play with May the Lord Watch. In both cases, group reunions doubled as reminders: Don’t sleep on the grown folks.

The idea of “grown-man rap” is a weird one. We embrace 22-year-olds for showing some world-weariness and acting like they have some perspective, but the moment someone manages to amass some actual wisdom, we turn it into a pejorative.

I wrote those words five years ago, when Sean Price unexpectedly passed away. At the time, rapping past 40 was still a punch line to people. But 2015 came in the middle of the decade that changed everything. The artists of the late ’80s/early ’90s golden era were all entering their forties (with a few ticking past 50), and their careers were maturing from chasing chart status into something sustainable.

Their old music lived on in catalog sales and commercial placements. They began branching out — acting, investing. They weren’t chasing trends, and they weren’t necessarily signed to the labels they’d started their careers with, but they didn’t need to be. They had their names, and they had the ability to push music to the world. They made what they wanted to when they wanted to, for audiences who wanted to hear what they had to say. Some even snared themselves a whole new fan base.

Read more: Revenge of the 40-Year-Old Rapper: A Roundtable Discussion

And they stayed sharp. Some of them managed, impossibly, to get better, their intelligence and accrued experience alchemizing into a formidable new weapon. E-40 dropped two of the best songs of his career — “Function” and “Choices (Yup)” — after he’d turned 45. Royce da 5’9” sobered up and started tearing down Babylon, albums like Book of Ryan and The Allegory vaulting him into a new weight class. Black Thought, at the once-unthinkable age of 46, went on Funkmaster Flex’s show and spewed a 10-minute broadside for the ages, a dissertation wrapped in the dozens. (“How much more CB4 can we afford?/It’s like a sharia law on ma cherie amour,” he rhymed, beads of sweat collecting on his forehead.)

This is just the beginning. In the next two or three years, Yo Gotti, Rapsody, Freddie Gibbs, Remy Ma, Skyzoo, Lil Wayne, Westside Gunn, and many more will all enter the fifth decade of their lives. Some of them are still rising stars; others have been in a groove for years. But all of them are still striving, and releasing some of the best work of their careers. And behind them, another generation of emcees is doing the same.

Getting older doesn’t only mean meditating on legacy and regret, the way Jay did on 4:44. Autobiography is an art best left to a few. But life happens, and its events and transitions can’t help but rewire the creative brain. Marriage. Parenthood. Loss. Vulnerability. Awareness of your place in the world. Inevitably, those things creep into your music, whether through subtext or sentiment. And for those of us whose paths have wound through similar points, music resonates somewhere deeper. It hits different.

Rap will always deliver new. Each emerging phenomenon, every Roddy Ricch or DaBaby or whoever else, will cut through the noise and captivate ears across the age spectrum. But those who are right there with those artists will have the distinct pleasure of growing with them, of watching them enter new chapters, navigate new challenges, and grow in unexpected ways. And hopefully one day, when both listener and artist have the luxury of looking back, those listeners will get the chance to tell those artists what that synchronicity feels like.

In 2015 — the year Sean Price died, the year of change in the middle of a decade of change — I interviewed Common again. Different magazine, different story. This time, the story focused on him and his mother, educator Dr. Mahalia Ann Hines. This time, I was newly 40. But one thing stayed the same. As we were wrapping up, I told him about the time we’d talked 15 years prior. He didn’t have an acting career yet, or an Oscar; he was in many ways at the very start of a creative career most would trade theirs for. “I bookmarked my life by your albums,” I said to him now.

“Thank you, brother,” he said in return. “I love to hear that.”

That was all that needed to be said.

Comments

Leave a comment