Jermaine Dupri’s got hits like Griffey Jr. He’s got joints for meeting at the altar in your white dress, for a topless Ferrari (or Jaguar) switching four lanes, for funk baptisms, for when you’re seriously down bad or ready to make a confession, for when their loving ain’t the same, for when the parties don't stop 'til eight in the morning, and plenty more. There are a lot of them.

The historic run began after a then-19-year-old Dupri happened upon two talented young teens at an Atlanta mall, turning the duo that would become known to the world as Kriss Kross into hip-hop’s first multiplatinum child stars by 1992. The following year, JD founded So So Def Recordings, which released albums from Xscape, Bone Crusher, Jagged Edge, Da Brat, 3LW, J-Kwon, and Anthony Hamilton. In 2000, Dupri proved himself as a kiddie-rap whisperer when he groomed Bow Wow into a superstar with twice as many hits as you likely remember at first thought.

Dupri’s profuse productions for Mariah Carey (“We Belong Together”) and Usher (“Burn”) in the aughts solidified his status as a monument of that era’s radio mainstays and dope deep cuts. Anyone who thinks Jermaine Dupri’s recently announced Verzuz with Puff Daddy will be a lopsided affair in favor of the latter needs to get a grip and check the damn résumé. JD’s been doing this for a long time, and he’s got more jam than Bonne Maman.

Related: Bow Wow and Romeo’s Respective Beefs With Mentors Are Sad to Witness

His most recent work comes by way of an unlikely pairing with Curren$y. For Motivational Use Only, Vol. 1, their collaborative EP, finds the mellow New Orleans rapper doing something rarely seen throughout his tenure as hip-hop’s greatest independent rapper: sliding over high-energy beats. This is the type of music you can cut a rug to, the type that made Dupri and his label a paramount part of the culture. The project’s lead single, “Essence Fest,” is a blend of Curren$y’s smooth flow and New Orleans bounce music that could tear up any Fulton County skating rink. So far, it’s one of the best rap records of the year. “It gives you a whole lot of different hip-hop energies from different eras,” Dupri says.

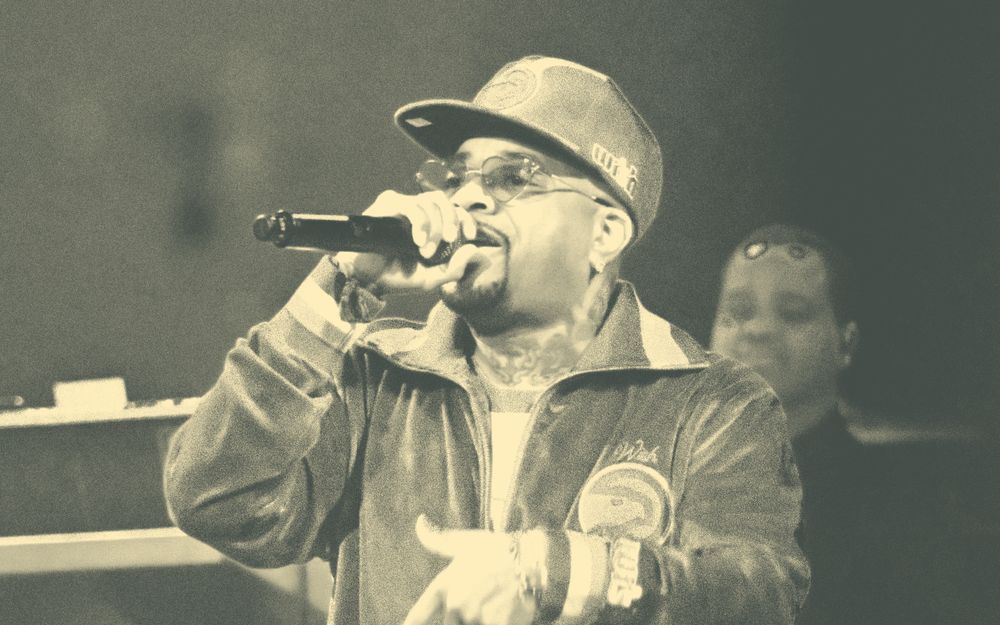

Jermaine Dupri hopped on Zoom with LEVEL to discuss his storied music career, fatherhood, veganism, why we should ignore fugazi AI-generated music creations, and why, after all of his success, he still feels like it's JD versus everybody.

—

LEVEL: It’s So So Def’s 30th anniversary this year. First of all, congratulations.

Jermaine Dupri: Thank you.

What do you think the label's legacy is?

I don't think that people think this, but I would say it's the young energy. The whole duration of it, you look to So So Def for the younger energy.

I'm sure you saw the Grammy medley to commemorate 50 years of hip-hop. I feel it was missing some things, namely your part and So So Def’s part. Do you feel the same way?

Yeah, I think that Grammy performance was a good showcase of what we had to go through being Southern artists and a Southern company. We was always last to get the phone calls.

How did For Motivational Use Only, Vol. 1 come together?

Spitta had a song on his last project titled “Jermaine Dupri.” [Rap Radar’s] B. Dot was like, “Jermaine, did you hear this?” From there, I hit up Spitta and I was like, “You need to come to a lab and make a song. That's the least I could do.” We set out to make one song and ended up making 50.

"It feels like somebody's been trying to create things [like AI-generated music] where the less talented can reap the benefits of those that's talented. I'm sure a lot of people probably don't agree—that's because they fit the description."

On this EP, you got Curren$y doing music that's more dancey and clubby than people usually hear from him. As a producer, how easy was it to get him to adapt?

It wasn't hard at all. I saw a message he posted the day before the album came out. He said he had been wanting to work with me since Kriss Kross. So I think he knew what he signed up for. He knew who he was working with. He came in there hoping I didn't try to match what other producers that work with him try to do. That in itself was the language he needed to get into that space, because he was like, Oh, he's not giving me these boom-bap beats I'm used to hearing, he’s actually giving me records he would rap over, records he would give to somebody else. That was the language I spoke to him. And he responded with what you hear.

I'm a big fan of the project. Y'all could have a run like Hit-Boy and Nas are having. What's next for you two?

We got the records, we just have to figure it out. Based on the reaction, we see people liking it. Let's continue to keep the vibe we got. We just gotta put it out.

+

What do you think is the current state of club music? As far as rap goes, there's a lot of stuff that compels men to rap aggressively in each other's faces. Not much dancing.

The pandemic shutting clubs down and people feeling like their only outlet was YouTube and Instagram, that derailed making music for a place a lot of people weren't going to. Hopefully, we can help get it back.

What's it been like having a hand in this gravitational shift where Atlanta became the mecca of hip-hop?

It's interesting, because on one hand we took over, but at the same time we was reminded at the Grammys that we haven't taken over. You know what I mean? It's still a stepchild type of situation. It's not a full-blown We in the house type of situation. I have mixed emotions about it. My feelings are different every day, because in one way, yeah, the South is killing it in media and radio—but we still get slighted on the media side. For the most part, media still wants to talk to more of the artists that come from New York and L.A. Not all the time, not everybody.

"If I was from New York, they would call me the greatest of all time."

One of the main people I felt should have been on that [Grammy] show was Luke Skyywalker. Even more than me. Because the parental advisory sticker on every album was because of Luke Skyywalker and the 2 Live Crew. That should have shifted the way you think about the presentation of 50 years of hip-hop.

In your mind, is there a difference between producing hip-hop and R&B, from an arrangement or a songwriting standpoint?

Yes and no. I write R&B records in the mindset of a rap record. I use call-and-response type of wording. How do people sing these Usher records so easily and know all the words? It's written in a way that reminds you of rap. The words I use for some of these songs feel like you're spitting a rap as opposed to singing a song. I don't do it deliberately; it just happens subconsciously.

Related: Only One Man Could Hold His Own With Usher in a Verzuz

There was a social media resurgence that exposed Ghost Town DJs’ classic 1996 song “My Boo” to a whole new generation. What was that like for you to have a Berry Gordy moment?

I don't know if I had a Berry Gordy moment.

I saw a video where you said only Motown has records that come back like this, 20 years later, like Berry Gordy.

I be saying that, but it's nowhere close. Nobody's been even close enough to even pull that off. I just, you know, I dream of it. But It's nowhere near that. He's definitely an inspiration though. I've got a big picture of Berry here in the studio.

You've done a lot throughout a decades-long career. What do you consider the peak of your career?

I don't feel like this, but I think people talk about Confessions and how that's this generation’s Thriller. With it being the last diamond record from a Black male artist in the last 20 years almost. That's what people equate it to. That was a big time just to go from that to [Mariah Carey’s] Emancipation of Mimi. They were almost five or six months apart. And then there’s things that I be forgetting about, like the one time when I held the No. 1, No. 2, and No. 3 spots on Billboard. I don't even know that I could ever possibly do it again, but just stuff like that. That's pretty mind-blowing.

The industry has changed so much that stuff like Billboard charts doesn't seem as significant as it did back then.

Well, no. Yes. I think so. I did it with two different artists, right? You see Drake do it and it's Drake by himself. You see Taylor Swift do it. But you don't see a producer/songwriter do it with two different artists. It’s almost like if 40 [Noah Shebib] produced Drake and Taylor Swift, then they could possibly do that. Or if Tricky [Stewart] and The-Dream did a song for Drake and Beyoncé at the same time. It's not something that's talked about, because there's not a bunch of people that actually do it.

Is there a low point in your career?

Moving from label to label. My Def Jam era was not the greatest for me. Sometimes you think just because you go to a team that's so big and they’re supposed to be able to do so much that life is going to be that much better and it's not always the case. It was almost too much talent in the building, too many people trying to fight for space. I need to be in a space where the people around me understand letting me run only makes them look better. That was probably the lowest for me. It was the time when I put out the least music.

+

How has fatherhood changed you?

It made me realize what really matters and what don't, you know? Beforehand, I would use the studio as a crutch for no reason. You can't do that. It made me realize that it's other things more important. It made me realize how fast the life that we’re living is. Life goes by quick; before you know it, you done spent like five years doing something that you probably shouldn't have been spending your time on. With kids, I don't have a choice but to move with what they’re doing. You gotta go to the school, you gotta go to everything that’s going on. I remember the first time I had to go to a game, I tried to tell my daughter I gotta go to the studio. My daughter said to me, “Ain't you the boss?” And I was like, “Oh, s**t. Okay, you might be right.”

"I'll be in the studio ’til like five in the morning—then I have to take [my daughter] to school at like seven. I'm tired, but I also want to do it. You just find that extra energy."

You have a grown daughter and a teenage daughter. Did the second time around change your approach to fatherhood?

The second time there's not even a question. It's just me moving to the beat I'm supposed to move to. Before I was questioning it, like, “Let me see if I can make it.” Now, I'm doing stuff I didn’t do with my first daughter. I wasn’t driving her to school and all that other stuff. I'll be in the studio ’til like five in the morning, so then I have to take her to school at like seven. I'm tired, but I also want to do it. You just find that extra energy.

Damn, when do you sleep?

After I drop her off. [Laughs]

Have you seen a change in yourself since you became vegan?

Yeah, 100 percent. You lose a lot of weight when you become vegan [and] you start feeling the difference in what food does for your body immediately.

What’s the difference?

Just the energy level. I’m from the South—we got this thing called the itis. You should never want the itis. Food is not supposed to make you sleepy. Food is given to us to energize. Food is energy. Food is supposed to make us run. Food is supposed to make us go jump higher than we supposed to be able to jump. Eating food in the South, you eat and go to sleep.

Of all the different foods you could’ve tackled, what made you want to jump into vegan ice cream?

Desserts for us vegans, it’s not plentiful. I hate going to restaurants and all my friends can get amazing desserts—tiramisu, crème brûlée, all kinds of things. I say, “What do you have for vegans?” And they say, “We’ll bring you a fruit plate.” I don’t want no f**king fruit. It’s a typical reaction I had, so I was like, let me make this ice cream. If we could get the ice cream into some of these places, people like myself will have a better option. It'll feel like they’re having a real meal with a real nice dessert.

+

Speaking of real, are you tuned into the advancements with AI, where people are turning people's voices into songs and—

I try not to pay no attention to it. We are already in such a bad space with music. We're getting ready to go into a rabbit hole we’ll never be able to get out of. Like, [if] this person can fake like they had a song with Jay-Z, it takes away from the fact that I have a song with Jay-Z. It feels like the world is trying to find a way to be as less talented as possible and still get the credit. It's been that way since Auto-Tune. It feels like somebody's been trying to create things where the less talented can reap the benefits of those that's talented. I'm sure a lot of people probably don't agree—that's because they fit the description of what I'm talking about. I don't believe we should give that any energy. We're gonna wake up one morning and hear a song on the radio that’s not real. We gotta go to the courts and shut it down immediately. Everybody got to be in agreeance, because it's not cool.

Related: Stop Being Shocked Jay-Z Is an Elite Rapper in Middle Age

In the beginning of your career, you were a dancer. I wonder if that’s a direct throughline that’s influenced the way you produce music.

I think so. Also, in the South, we skate. When me and Usher started skating and putting it on Instagram, people was like “Man, y’all still be skating out there?” Skating’s never going away in Atlanta. The skating rink is a staple. It's been going before I was old enough to go and it'll be going when I’m too old. It's part of our culture.

That's another thing, I don't remember in my early interviews [being asked about] the culture of Atlanta. We came into this and they was trying to hold us out like, “Atlanta, y'all too country.” I think half of our culture don't understand what happens here. They think we do stuff in a trend wave, as opposed to how New York has culture, Chicago has culture, and there’s gang culture in L.A. It’s things in Atlanta that’s staples, but they don't talk about them. That has to change. I tried to do that with “Welcome to Atlanta,” to make people realize this is how we move in the city.

But culturally, my music is danceable because, yeah, I came up as a dancer and I go to skating rinks, I go to clubs, and I actually want to dance. I don't want to just stand around. It's in the energy of the person who's making the music.

Do you feel you're underrated as a producer and performer?

One-hundred percent.

Why is that?

Because I'm not brought up in these conversations about the best hip-hop and R&B producers. I don't have to be the first name that comes out of people's mouths, but you know, at least the fifth. I should not be no nine. I saw a list about CEOs and I damn near didn't make the list. How was that possible? It's crazy to me.

My mother listens to this Sirius XM station where they play all the ’90s and 2000s hits. She called me and said they played five Jermaine Dupri records back to back. And I'm like, man, am I the only person that pays attention to this? Is it like a thing where you’re supposed to ignore the fact that this is happening? It's the same thing as when we were talking about the [Billboard] chart [record]. Hit-Boy, Metro Boomin, Swizz Beatz, Timbaland, Dr. Dre—you can name all of them. They've never held the No. 1, No. 2, and No. 3 spots on the Billboard. Never. If I was from New York and I held that space, they would call me the greatest of all time.