Juel Taylor’s directorial debut features fried chicken that makes you bust a gut, purple goop that relaxes more than just your hair, and an artificially flavored drink that will make you want to cut a rug. Yet when it comes to his audience, the filmmaker has no interest in mind control.

“I don't ever want it to seem like I'm trying to lead a viewer to the same conclusions that I came to,” says the Tuskegee, Alabama native, who, along with Tony Rettenmaier, wrote the highly anticipated film, They Cloned Tyrone, a brain-bending sci-fi comedy that seeks to entertain just as much as it provokes thought. "The last thing I would want is someone to think that I'm trying to preach to 'em."

The movie dreams up a conspiracy concocted by unseen forces to control+alt+delete the Black residents of The Glen, a nondescript, fictional Southern ’hood held up/down by hustlers (John Boyega), pimps (Jamie Foxx), and sex workers (Teyonah Parris). These unfit investigators find themselves following a breadcrumb trail to foil the suspect scheme.

They Cloned Tyrone (out in limited theaters now, ahead of its Friday release on Netflix) is one of those films you’ll have to watch twice, maybe thrice, to catch all of the references, Easter eggs, and narrative flair. And while the 36-year-old Taylor had a heavy hand in crafting the story, he’s hesitant to over-explain his intentions or inspiration. He’d rather you extract your own meaning.

We asked him anyway.

The result? A spoiler-free deep dive on one of the year’s trippiest films. Buckle up!

Editor's note: This interview took place in June 2023, prior to the SAG-AFTRA strike.

LEVEL: Tell me what this moment feels like for you: You’re making your directorial debut on a highly anticipated film that has been in the works for several years. Where’s your head at right now?

Juel Taylor: It feels very normal, in the sense of day-to-day. The public-facing part has yet to fully settle in. In some ways, it's been chill. The intense part of getting it out into the world has only just started. Maybe it’s because I've been living with it for so long, emotionally I've detached enough to be like, alright, it’s in the world. So I'm not necessarily nervous because I expect nothing. [Laughs] Of course, you're nervous on some level, but it's done. Otherwise, I would just be obsessing over every person's opinion… [I] have to remember: I was hyped about this at one point. Super excited. I've seen it too many times to know if it's any good.

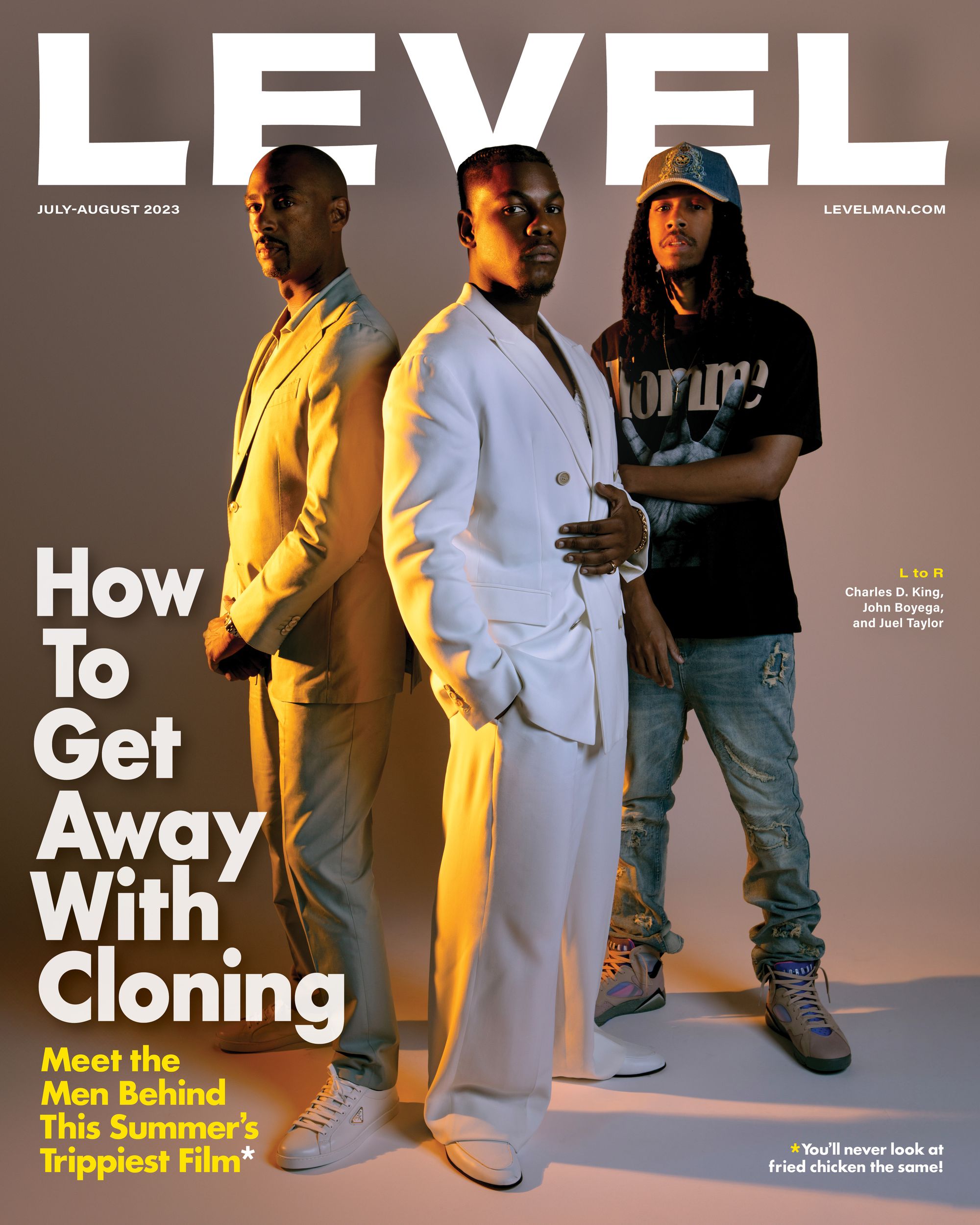

Related: John Boyega Has a Conspiracy Theory to Share

The excitement around the script when it was on the Blacklist suggests it’s very good. Take me back to the beginning. How did They Cloned Tyrone come to be?

We had the idea by, like, 2016 [or] 2017 to make a detective story about ill-equipped detectives. That story started to crystallize over time. But it wasn't until 2018 where we actually took it out and pitched it.

It wouldn’t be surprising to see Tyrone garner comparisons to Get Out and Sorry to Bother You, but this movie has been in the works since before either of those were released. What are your thoughts on how the film landscape impacted this project during the pitching stage and now that it’s set for release?

In general, I think those movies coming out helped us. Especially Get Out. You're pitching places and they're seeing, okay, Black genre is viable. I'm sure that opened the door in some ways. It was a warm landscape. Places were receptive. I don't know if Sorry to Bother You was out when we pitched it.

Related: LaKeith Stanfield’s Toughest Role of All Is Himself

Let’s talk about the Black sci-fi. I love how the genre provides a space to make an artistic statement or provoke thought, while also getting weird as hell.

I feel like in any genre, the more idiosyncratic and specific you are, the more people are going to gravitate towards it because it’s gonna feel new. That applies to any race, if it’s something that’s culturally specific. Take it back to Get Out—when you're making [They Cloned Tyrone], just by proxy, you have to be aware of Get Out. You have to make sure you have something that feels distinct. Because [the comparisons are] coming regardless. I don't think it's a bad thing, though. It's a good thing. But some people will naturally be dismissive of anything that comes after in a way they wouldn't be if it had come before.

“We’re sitting on the floor, crying. I'm talking like, four or five hours. I kept thinking about that conversation over and over.”

You’ve spoken about the inspiration of They Cloned Tyrone coming from the idea of blame versus responsibility. That feels like it could be very applicable in the real world—particularly regarding Black people in America, or any oppressed community.

We didn't set out to say anything about society. It was just something I was thinking about a lot. Something that bothered me. A homie of mine was in a situation where some bulls**t happened to him and it was outside of his control. I hadn't seen him in a couple years… I was so frustrated with him [because] he hadn't succeeded to where I knew he could. This dude is smart, funny, outgoing—like, damn, what's going on? He stayed in the hole for a long time, became a hermit crab.

I reconnected with him on New Year’s, either 2016 or 2017. We were riding around looking for something to do and everything was closed. I feel like somebody got to fighting or shooting at the club, so it was already emptied out. We ended up back in my house and he was just talking like, “Man, I was depressed, that's why I was so reclusive.” I wasn't even thinking about it from that point of view. We’re sitting on the floor, crying. I'm talking like, four or five hours. I kept thinking about that conversation over and over. The movie didn't really become a thing until I had a conversation with him. I talked to my writing partner Tony about it. That s**t really bothered me, in terms of my perspective on the situation. Not the conversation itself—the years leading up to the conversation. I didn't see that my friend was depressed. I was like, “Come on, get your s**t together, brother.”

That's where that blame-versus-responsibility question came in. Obviously, this is a highly dramatized version of that conundrum. But spiritually, Fontaine is in a similar situation, in some circumstances that are well beyond his control. Is he going to take the agency for himself? They didn't put themselves in this position, but the people who did aren't gonna help you get out of the hole if they put you there.

What Fontaine is really trying to find isn't who did this—it’s who am I? So there's a lot behind what we explore; just how responsible is he when we meet him versus when we leave him. [There’s a scene] where one person wants to bury their head in the sand like an ostrich when they see a problem, one wants to get somebody else to fix it, one don’t give a f**k about the problem. The points of view on that question are all different.

Given the trope of Black women so often being on the front lines of fighting oppression, how conscious of a decision was it to make Teyonah Parris’ character, Yo-Yo, the one who is the driving force behind getting to the bottom of the conspiracy?

We talked with Teyonah a lot about it. You're definitely aware of every trope. Narratively, is the juice worth the squeeze? Because you're gonna fall on the wrong side of a trope for someone, now matter how you write the story. So you try to be mindful of that and give the character enough dimension so she doesn't seem like a Mary Sue. But we weren't afraid to let Yo-Yo be the brains of the operation for fear of someone like, “Why women always gotta be cleaning up the mess.” We really tried to make sure she felt like she had a lot going on beyond stereotypes. You're gonna have blind spots…

I'm from Alabama; I know people who won't eat chicken in front of white people… This movie is having fun with that discomfort.

Yeah. Everyone does.

We leaned on Teyonah to take ownership of that character and bring her perspective to it. Keep us honest in terms of making sure she feels like someone she would f**k with. When it came down to the storytelling, it’s like, what makes the most sense narratively? It comes down to the details—how we build out her life, what we reveal about her, the mise-en-scène, the production design. Hopefully it all cumulatively adds up to create this character that feels well rounded and not like she's here to serve one narrative purpose.

Let's talk about the symbolic use of fried chicken, grape drink, and hair relaxer in the film. Why did you decide to associate those Black culture staples with control?

Something I always think about is, people have told me to cut [my locs]. “You should cut them if you're gonna do XYZ.” But why? Because white people think I'm not as smart as I am? I went to college. I went to grad school. If my hair is short, it changes nothing. No matter what you wear, your IQ ain't gonna change. The reason I say that is there's the specter of how white people see us. In this neighborhood, there's a level of curation involved. Trying not to be didactic here, but is this neighborhood’s lack of investment organic or is it by design?

I'm from Alabama; I know people who won't eat chicken in front of white people. When you think about control, it goes hand-in-hand with… I don't want to say white gaze—I hesitate to use such a dissertation kind of term like that. It's really like a matter of perception. These people are using things that are part of our culture to influence us. There's a bit of fun with the meta commentary. I know how it looks. But that's also how the people who curated the neighborhood are looking at people in the neighborhood. We worked backwards from every conspiracy theory, like, What if The Man is holding us back? What if The Man is feeding us these images?

We worked backwards from every conspiracy theory, like, What if The Man is holding us back?

At the heart of it, there's nothing wrong with going to the beauty [salon] and getting your hair done. There's nothing wrong with eating fried chicken. But if there were no white people, that scene wouldn't be offensive. The movie is having fun with that discomfort. They're in a neighborhood that literally has overseers. The question at the heart of that section of the movie is, Did this naturally come to be this way or was this curated by some unseen hand?

Who is to blame, and who is responsible.

You look at [impoverished] neighborhoods and people want to blame the people who live there. It's more complicated than that. Way more complicated than a movie could explain it. You’re ignorant of any number of things that could have been external factors. If you see a homeless person, maybe you don't know everything about how that person came to be there. Maybe they are trying to get a job. Maybe they've been trying every day at the library, applying. You don't know what they got going on. We all do it in some ways. It bothers me knowing that I've done it, even if I'm not necessarily consciously aware.

That was what we were thinking about when we were writing and working on it. We weren't necessarily trying to lead anybody to any conclusion. Hopefully you're watching and you just enjoy this movie. If it's on your mind afterwards, even better. But I’m very careful not to prescribe meaning. I could tell you it means this and that. But if you watch it and you're like, I didn’t get that, it is what it is. Don’t belong to me no more.

CREDITS

Design: Paul Scirecalabrisotto (@paulscirecalabrisotto)

Stylist: Tracy Shapoff (@tracyshapoff)

Juel Taylor wears a hat, shirt, and, pant Homme + Femme, and sneakers by Nike/Air Jordan. Jewelry is his own.

Comments

Leave a comment